|

| US soldier equipped with Quiet Pro. |

Deluged by images and reports of maimed and bloodied soldiers, it’s hardly surprising that the general public is largely unaware that the primary disability in terms of numbers among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans is the “invisible” injury of hearing loss and the related problem of tinnitus. A recent Associated Press article cites a Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) report that tabulates that nearly 70,000 of the almost 1.3 million troops who have served in the two war zones are collecting disability for tinnitus, and more than 58,000 are on disability for hearing loss. In 2006, the VA spent a reported $539 million on payments to veterans suffering from tinnitus, a figure expected only to rise as more veterans return and the wars continue.

The powerful roadside bombs that typify the Middle East battlegrounds cause violent changes in air pressure that can rupture the eardrum and break bones inside the ear, and since the attacks often come unexpectedly and suddenly, there is little time to properly utilize available hearing protection.

“The numbers are staggering,” says Theresa Schulz, PhD, CCC-A, PS/A, Lt Col (ret) USAF, past president of the National Hearing Conservation Association and a 21-year veteran army and air force audiologist. Schulz penned an article in 2004 for Hearing Health magazine titled “Troops Returning with Alarming Rates of Hearing Loss,” confirming the epidemic proportions of the problem. Since then, she affirms, the military has substantially intensified its efforts to reduce the frequency and severity of the problem.

Schulz believes that while there have been substantial advances on the technological front with the development of new hearing protection devices, the most fundamental issues are training, motivation, and awareness.

“The important thing is to prevent the damage before it happens—people need to first of all value their hearing and to learn how and when to wear hearing protection,” she says. “There has been a lot of activity in the VA and military to deal with this. For one, to learn the extent of the problem, a questionnaire about hearing loss and tinnitus is issued to all troops before and after they deploy. Also, the 2007 edition of Deployment Guide, published by Ameriforce, which typically deals with such issues as helping soldiers to learn about insurance and wills and the like, currently includes a section titled ‘Now Hear This,’ which focuses exclusively on hearing-related matters.”

|

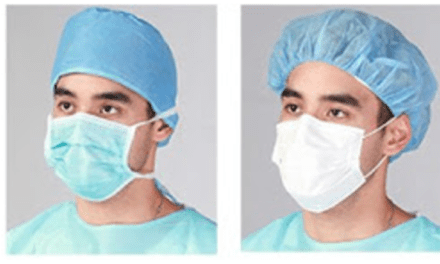

| Combat Arms Earplug (left), Quiet Pro (right) |

NEW TECHNOLOGIES, HIGH AND LOW

Research in new technologies has also gained momentum, and at least two recently developed hearing-protection devices have become widely employed. One is Quiet Pro, a sophisticated high-tech device that is especially adept at maintaining situational awareness for infantry in noisy combat situations, allowing “soft” combat sounds to come through while providing effective noise reduction of loud blasts. Manufactured by the Norwegian company Nacre (with offices in Aberdeen, NC), Quiet Pro is a digital, lightweight tactical communication headset with built-in intelligent high-level hearing protection. It is especially useful for radio communications and comes with the capability to connect to one or two radios.

Among Quiet Pro’s features are natural directional hearing, automatic Active Noise Reduction (ANR), compatibility with many types of helmets and protective gear, and—most importantly—protection from hazardous impulse and continuous noise without compromising the ability to hear and communicate. Continuous low-frequency rumbling noises above 85 decibels, such as that produced by armored vehicles, helicopters, and large engines, activate the automatic ANR to achieve attenuation of about 30 decibels—sufficient to endure these noises for lengthy periods without the risk of hearing damage.

Extremely loud impulse/impact noises such as bombs and artillery blasts, which produce the greatest threat of permanent hearing loss and attendant tinnitus, are instantly shut out by a digital processor that monitors sound waves sample by sample at a speed of 64,000 samples per second. But as quickly as these sounds are turned down to nonhazardous levels, normal amplification is restored for hearing ordinary sounds immediately after the impulse/impact sounds have passed.

|

| Neuromonics’ Oasis |

The Quiet Pro system consists of an in-ear headset connected to a control unit that is worn on the flak jacket. The headset consists of two earpieces attached to a disposable canal tip, and the control unit contains the electronic components, including the digital sound processing ASIC and the user interface.

At the opposite end of the spectrum from Quiet Pro in terms of cost—Quiet Pro runs about $1,400 per unit when purchased in volume—is the Combat Arms Earplug, which costs less than $10 per pair but provides effective reduction of damaging impact noises without significant attenuation of ordinary sounds. It was originally developed in France in the late 1990s, and its inventor, Armand Dancer, teamed with an American company, Aearo Corp, Indianapolis, to mass produce the device, which features a unique acoustic filter no larger than a rice pellet. The filter creates acoustic friction to capture potentially harmful sound waves and turn them around so that the noise doesn’t send signals into the ear canal.

“There have been devices before,” Schulz says, “that use valves and electronics, but impact noise is so fast, traveling in milliseconds, that you need a really effective device to dampen it. The Combat Arms Earplug has been around for 5 years, but because it doesn’t block ordinary sounds, it was not well understood or utilized in the beginning due to lack of education and training. Now it is being used much more effectively.

“The best earplug,” Schulz concludes, “is one you’re going to wear, and that requires adequate training in combat-type environments prior to deployment.” Crucial training is getting a boost, she says, by a recent uptick in recruitment of audiologists to serve in front-line hospital settings.

Schulz’ confidence regarding the future of hearing protection in the military is seconded by Col Kathy Gates, who, like Schulz, is a 21-year armed forces veteran, still serving as an audiology staff officer and consultant to the Army Surgeon General.

Gates, who holds a doctorate in audiology, is convinced that the military has “moved forward in focusing on prevention efforts in hearing loss and ringing in the ears.” Although the Army has had audiologists deployed in combat support settings since January 2003, it is the Hearing Readiness Program (HRP), first implemented in September 2006, that has really ramped up the hearing protection and treatment services available to both soldiers and civilians in deployment situations. The HRP is part of the broader Army Hearing Program (AHP), which in turn evolved from the longer-standing Hearing Conservation Program (HCP). A close look at the HCP resulted in a determination that more needed to be done in terms of providing soldiers and civilians with hearing services in operational settings, ie, deployment situations.

“The Army Hearing Program,” Gates says, “is designed to provide hearing services to soldiers and civilian noise-exposed workers in all environments (garrison, training, operational, and combat missions).”

As Gates describes it, the AHP consists of four major components: hearing readiness, clinical hearing services, operational hearing services, and hearing conservation. The combination of services is designed to promote and increase soldier and civilian awareness of hearing and the importance of maintaining normal hearing for good situational awareness and voice communication in any environment, including combat settings.

Recent AHP initiatives include the first audiologist deployed with a division in Iraq. Stationed at a combat support hospital, just one audiologist is deployed at this time, but that person (whose identity must be protected for security reasons) “has,” according to Gates, “been very successful in setting up satellite hearing clinics in Iraq where technicians can test soldiers for hearing problems and refer them to the audiologist as necessary.”

As for Afghanistan, there is presently no audiologist permanently deployed there, but one stationed in Europe visits the hearing clinics in combat hospitals to provide support.

“Since the expansion of hearing test sites in 2007,” Gates says, “more than 7,000 hearing-injured soldiers have obtained immediate hearing evaluation, treatment, and intervention in-theater. Prior to this expansion, hearing-injured soldiers were not seen in-theater and usually obtained hearing services [only] upon redeployment.”

The two leading hearing protection devices are once again the cost-saving Combat Arms Earplug, issued to all soldiers as part of the Rapid Fielding Issue, and the more expensive high-tech Quiet Pro. As previously stated, the Combat Arms Earplug allows most speech to pass through with minimum attenuation while protecting against hazardous combat-related noises such as bombs and artillery. The Quiet Pro, part of the Rapid Equipping Force Initiative, is a tactical communication and protective system that has been widely embraced by the Marines and is currently being tested and evaluated by the Army.

“Soldiers not only want to hear, they want to hear well,” Gates says. “Use of this type of device allows for both hearing enhancement and protection.”

Also, because, as Gates puts it, “a one-size solution does not fit everyone,” the Soldier Enhancement Program has been tasked to develop a Qualified Products List in order to provide soldiers with a selection of alternative choices in tactical communication and hearing protection devices.

“The Army,” says Gates, “is very excited about our road-ahead mission in moving the AHP forward. We are no longer accepting hearing loss as a by-product of military service.”

ON THE TINNITUS FRONT

Regarding tinnitus, Theresa Schulz cites the approach of the American Tinnitus Association in likening the problem to a pyramid-like structure. “There are several levels of sufferers of tinnitus. The biggest group is at the bottom of the pyramid, which includes everyone who at one time or another has experienced ringing in their ears. That’s a relatively harmless level of the problem. The next level up consists of those who have the problem often, where it becomes repetitive and chronic. Above that is a smaller group who have it all the time and are really bothered by it, and at the very top are the relatively few for whom tinnitus is very debilitating, causing continuous suffering, including inability to sleep or function normally in daily life.”

It’s important to understand, Schulz emphasizes, that tinnitus is a symptom of hearing damage, rather than an autonomous disability, and there is no known cure for it. However, the ailment can be controlled and mitigated using biofeedback-type techniques that in essence retrain the brain so that the patient is less vulnerable to the disturbance. “People also need to learn basics such as knowing that caffeine and nicotine can make tinnitus worse.”

|

| Teri Sinopoli, MA, CCC-A, FAAA |

Teri Sinopoli, MA, CCC-A, FAAA, is an audiologist specializing in the treatment of tinnitus. Since 2006, she has been director of clinical services at Neuromonics, Bethlehem, Pa, where the only currently FDA-approved tinnitus treatment is the featured product. A 6- to 8-month therapeutic program combining education and counseling with a pocket-size MP3-like device called the Oasis, the Neuromonics tinnitus program provides the patient with acoustic stimuli in the form of customized music and an embedded neural stimulus. Originally developed in Australia by Dr Paul Davis, the treatment’s musical program, which is based on the patient’s hearing profile, consists of four selections, each 1 hour long, that provide an enriching and engrossing environment to aid in effectively retraining the patient’s response to tinnitus.

“Tinnitus is a symptom of hearing loss,” Sinopoli explains. “The brain notices something is wrong and tries to compensate for the hearing loss, turning up its own internal gain.” When this happens, says Sinopoli, tonotopic organization in the auditory cortex becomes upset, and the result is the buzzing, ringing, and chirping sounds of tinnitus. “We used to think that lack of hair fibers in the inner ear caused tinnitus—now, as a result of research in the last 10 to 15 years, we understand that tinnitus is generated by the brain.”

The Neuromonics approach is to create a stimulus that will result in neuroplastic changes leading to cortical reorganization, in effect retraining the brain to reduce the debilitating effects of tinnitus. The treatment is used by the patient for 2 to 4 hours a day, during which the patient is free to engage in any activity except driving or watching television.

Specifically, there are two phases to the treatment. The first phase lasts 2 months and includes a low amplitude “shower” sound that is embedded in the musical selections. This masks the tinnitus so that the patient is not exposed to the disturbing noises, gets immediate relief, and is able to feel empowered about controlling the debilitating effects of the problem.

In the second, 4-month phase, the shower sound is removed as the patient continues to listen to the customized music. While the musical peaks cover the ringing sounds of tinnitus, the ringing is audible during the lower-amplitude troughs in the music.

“The patient hears the tinnitus intermittently, becoming desensitized to it and learning how to dismiss it even though they hear it on occasion,” Sinopoli says. “By stimulating the brain, we’re trying to get it back to its normal pitch order.”

|

| Col Kathy Gates |

Akin to biofeedback, the psychological element in the process is important, as the relaxing music engages the brain’s limbic system to help calm the patient, and the provided counseling helps the patient become educated about tinnitus so as not to be fearful of it. The initial two phases are followed by the maintenance phase, during which the patient uses the treatment from time to time, perhaps two to three times a week.

As for the effectiveness of the program, Sinopoli says, “We are very pleased with results. Neuromonics has observed a significant increase in the number of audiologists recommending the product, and about 200 clinicians in the United States have been trained to administer the treatment. As a result of clinical trials, we are finding that 90% of patients who went through treatment have had at least a 40% improvement, and even a 20% improvement is considered significant in the treatment of tinnitus.”

She adds that there are currently about 1,000 patients undergoing the program in the United States, with approximately 200 of those cases military-related. Cost of the treatment typically ranges from $3,500 to $5,000 (depending on the individual clinic), and it is expected that insurance coverage will become more readily available as proven results continue to accumulate. The FDA cleared the product as a Class II medical device in 2005.

Delving deeper into tinnitus, indeed, into the inner ear itself, we come to the “Hearing Pill,” a relatively new therapy that has both its advocates and detractors. The Hearing Pill, originally developed and patented by the US Navy in conjunction with San Diego-based American BioHealth Group, is an attempt at a pharmacological solution to the problem of tinnitus. Focusing on the cochlea, The Hearing Pill emphasizes biological processes that are believed to be related to hearing health, such as reducing the presence of toxic compounds in the inner ear that are destructive to the cochlea’s hair cells, which are the cells that turn sounds into electrical signals that travel to the brain.

The key ingredient in The Hearing Pill is n-acetylcysteine, which, according to American BioHealth Group, “has been demonstrated in laboratory studies, as well as in anecdotal evidence, to help protect and restore damage from acute (near-term) noise-induced hearing loss.” Specifically, the company claims that The Hearing Pill, which is a nonprescription nutraceutical product, will improve glutamate excitotoxicity, restore glutathione (necessary for hearing health), suppress reactive oxygen species, provide mitochondrial protection, and prevent premature cell death. A disclaimer notes that, with regard to the drug’s ability to protect and restore hearing, “It has not been shown to demonstrate these same capabilities for genetic, tinnitus or autoimmune disorders.” A study in 2003 on 566 recruits did show a 25% to 27% reduction in permanent hearing loss.

|

| Theresa Schulz, PhD |

Using the pill involves taking two capsules twice daily before entering a noisy environment. “After experiencing noise trauma,” states company literature, “see your physician immediately and take two capsules three times daily for 30-60 days to attain the most positive results.” There is also cautionary advice: “You should always practice sound hearing conservation programs including wearing hearing protection and reducing the noise insults in your environment.”

Another clinical trial conducted by the Navy, as reported in the ASHA Leader (June 2005), demonstrated that n-acetylcysteine “reduced permanent hearing loss in the ear closest to the source of the acoustic trauma.” Nearly 1,000 Marine recruits participated in the study, which involved their exposure to 300 rounds of M-16 fire in the course of 1 week. Navy commander and otolaryngologist Ben J. Balough said, “Our goal is to provide something akin to a nutritional supplement to provide additional hearing protection for noise exposure over and above that obtained from standard ear plugs.” The trial, the report noted, also “showed potential for healing symptoms of acoustic trauma such as tinnitus and balance disorders.”

Although there are those who doubt the effectiveness of this approach in substantially alleviating tinnitus, a very recent (May 2008) article in Medical News Today cites the case of audiologist Ernest Moore, who is also a cell biologist at Northwestern University, and whose own hearing was damaged by military explosions during his 20 years in the US Army Reserve Medical Corps.

Working with zebrafish, which have an ear structure very similar to that of humans, Moore has been able to induce tinnitus-like reactions in the fish by exposing them to certain drugs that produce intensified electrical firing in the hair cells of their inner ears, a characteristic of tinnitus. He has then exposed them to other drugs that reverse or block the tinnitus-like behavior by slowing down the electrical firing. Preliminary testing has indicated positive results, and Moore is meeting with physicians to discuss clinical trials to test these drugs on humans with tinnitus. “If the hair cell is just beginning to break down,” says Moore, “and you administer these drugs, you might be able to prevent further damage and interfere with the cell’s ability to generate tinnitus.”

|

| Lucille Beck, PhD |

An overview on this subject is provided by Lucille Beck, PhD, Director of Audiology and Speech Pathology for the Department of Veterans Affairs and Chief Consultant for VA Rehabilitation.

“Actually,” she says, “there are various theories regarding the cause of tinnitus, including wax on the eardrum, damage to part of the middle ear, and failure of the efferent nervous system’s ability to report hair cell dysfunction, which results in a loss of the normal suppressive function.”

Beck believes that what is really important is to be aware that there is a subjective component to tinnitus that is different for every individual, “and to acknowledge when an individual complains of tinnitus and provide them with the information and education they need to understand and deal with the problem.” She also stresses the importance of research: “We have to ask our researchers to continue to study tinnitus to really find out what the cause is.”

Beck acknowledges that tinnitus has surpassed hearing loss as the primary disability among veterans of the Iraq/Afghanistan wars—although not by very much. “For the fiscal year of 2007, there were 69,592 cases of veterans who have been service-connected for treatment of tinnitus, and 58,179 for hearing loss, all resulting from the OEF/OIF wars.”

Most importantly, Beck stresses that the VA has recognized for years that hearing loss and tinnitus are occupational hazards of military service, and has “a strong commitment to provide veterans with state-of-the-art hearing health care in both diagnosis and treatment.” There are currently 220 clinical hearing sites nationwide, with 647 audiologists working in the VA. A full continuum of services includes hearing aids, cochlear implants, and many assistive technologies, as well as training for audiology students and support of research on hearing loss and tinnitus management.

“Hearing damage from these wars follows the same general trend as previous conflicts like Vietnam and World War II,” Beck says. “Of course, with the proliferation of IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices), especially in Iraq, we are seeing multiple problems as a result of blast injuries, such as traumatic brain injury and other physical injuries.” Nonetheless, in terms of frequency, hearing damage, in particular tinnitus, is the leading disability among veterans.

Other than the numbers, there is nothing especially eye-opening about this issue. If “war is hell,” then hell is noisy, so soldiers will suffer hearing damage. The military and the VA, however, are working diligently to mediate the problem, and seem confident of prevailing in their mission, as Col Gates has stated, to “no longer accept hearing loss as a by-product of military service.”

Alan Ruskin is staff writer for Hearing Products Report. He can be reached at [email protected].