Tech Topic: Fitting Technique | May 2014 Hearing Review

By Robert W. Sweetow, PhD; Sueli A. Caporali, PhD; Patricia M. Ramos, AuD; Cathi Ahrens Berke, BC-HIS; and Ellen Finkelstein, AuD

Approximately 50% of hearing aids fit in 2013 in the United States were mini-BTE RIC (receiver-in-canal) or RITE (receiver-in-the-ear) devices.1 These numbers are expected to grow in the future.

Among the reasons consumers prefer these devices are superior cosmetics and comfort.2,3 In addition, better feedback control allows for an increase in open fittings.

Unfortunately, despite these improvements, problems related to cosmetic gaps (between the thin earwire connecting the hearing aid to the receiver and the side of the head) and lateral migration persist. Lateral migration is characterized by the need to frequently push the receiver back into the ear canal because of lateral movement due to jaw motion. The prevalence of these problems is not trivial, as will be shown below.

Anatomically, the ear canal is defined as the area extending from the concha to the tympanic membrane. The structure of this canal consists of elastic cartilage in the lateral one third (the cartilaginous portion), and porous bone covered by thin skin in the medial two-thirds (the osseous portion). Distinct angles in the horizontal plane occur at the first and second bends.4 The ear canal initially courses anteriorally, then turns posteriorally, before resuming an anterior orientation again. In addition, the canal changes its vertical direction. There is an upward swelling of bone just medial to the osseo-cartilaginous junction. This upward bony prominence results in a narrowing of the canal at the isthmus.5 Thus, although the exact shape of each ear canal varies, in general it can be visualized as an irregularly coursed and elongated “s-curve.”

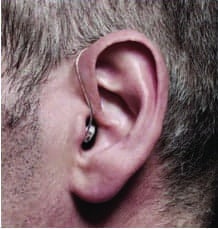

Traditionally, most receivers are connected to the hearing aid via an earwire that courses vertically from the center of the receiver head and then bends at approximately a 90° angle horizontally into the ear canal. But this is not the course that the ear canal takes. Thus, current arrangements would be analogous to trying to fit a round peg into a square hole. As a result of this mismatch, cosmetic gaps are frequently seen between the earwire and the side of the head (Figure 1a).

Figures 1a. The illustration shows a front view of a cosmetic gap (ie, gap between tube and side of head).

In addition, there is a dynamic variation between the osseous and cartilaginous regions when a person speaks or chews. So, once again, the dimensions of the ear canal change. This alteration in diameter consistency can produce lateral migration of the earmold or RIC (Figure 2a).

When the jaw is closed, the head of the jaw (condyle) rests on a disc in the fossa. As the jaw opens, the condyle pivots. As the jaw opens wider, the pivot point literally moves forward toward the front of the head over a protrusion called the articular eminence. Thus, the anteroposterior width increases when the jaw is opened. The osseous portion limits the part of the canal that can be changed by the jaw action to the anterior and somewhat inferior aspects of the canal. This is why a deeper fit, if comfortable, can limit lateral migration.

Adding to the problem is the fact that some of these changes in shape and orientation increase in older ears. Oliveira6 showed 4 of 7 subjects older than 60 years have more than a 30% increase in canal volume (from entrance to second bend) in at least one ear with jaw opening. Moreover, asymmetric volume changes are not uncommon.6,7

Survey: So How Common Are These Problems?

As part of the project described in this paper, data were collected to determine the prevalence of cosmetic gaps and lateral migration as reported by experienced clinical hearing healthcare professionals (HHPs). A live survey was conducted by one of the authors (RWS) at educational meetings held in five separate states. A total of 284 participants (audiologists and hearing aid dispensers) were asked to confidentially respond (in writing) to the following instructions:

1) Please estimate the percentage of your mini BTE RIC instant dome patients who experience lateral migration issues (defined as the earpiece working its way out or partially out of the ear canal), or needing to frequently push the earpiece back into at least one of their ear canals;

2) Please estimate the percentage of your mini BTE RIC instant dome patients whose physical fit creates a gap between the thin wire and the side of the head.

Responses were obtained from 232 attendees (a return rate of 80%)—the remaining 20% either chose not to respond or indicated that they did not fit hearing aids enough to make a determination.

Figure 3a. The figure shows the prevalence of lateral migration as reported by survey respondents, with the range of estimated prevalence (in percent) shown in the x-axis and percentage of responses shown in the y-axis.

Figure 3b. The figure shows the prevalence of cosmetic gap, using the same x- and y-axis designations. (Note: vertical axis depicts a 0-25% range.)

The results are shown in Figures 3a and 3b. In both of these figures, the x-axis refers to “Range of reported prevalence (in percent)” and the y-axis refers to “Percentage of responses.” For example, in Figure 3a, 22% of the surveys indicated that lateral migration occurs in 20-29% of their patient fittings, and 17% of the surveys indicated that lateral migration occurred in less than 10% of the patients. In Figure 3b, 15% of the surveys indicated that cosmetic gaps were present in 50-59% of patients, and 17% of the surveys indicated that gaps were present in 20-29% of the patients. The median prevalence of lateral migration is 27% and the median prevalence of cosmetic gap is 34%. Therefore, it can be concluded that these two issues are highly significant in this clinical population.

A Solution for Cosmetic Gaps and Lateral Migration

When cosmetic gaps and the need to frequently push the receiver back into the ear canal occur, users, as well as HHPs, are inconvenienced, frustrated, and even embarrassed. As a consequence of these concerns and their widespread occurrence, Widex has developed a new, patented wired RIC solution, called EASYWEAR, which integrates the receiver and the earwire. The parameters of the receiver and earwire have been modified to obtain a better physical fit and stability in the ear canal. Specifically, two major revisions have been applied:

Figure 4. Left: EASYWEAR with multiple earwire angles. Right: Standard receiver with typical earwire angle

1) Unlike “standard” earwires that course in a horizontal direction straight into the ear canal, the new earwire is reinforced with Kevlar fibers and shaped to direct the receiver at multiple angles (Figure 4) that mimic the majority of human ear canals, as explained above. Notice the stark difference in the angle of the EASYWEAR receiver.

Figure 5. Left: EASYWEAR with the lateral connection. Right: Standard center connection of the earwire to the receiver.

2) The connection between the earwire and the receiver has been moved from the center of the top of the receiver to the lateral portion in order to allow for a closer proximity between the earwire and the side of the head (Figure 5). Maintaining a center connection (as is presently the case for earwires and receivers) commonly creates gaps as shown in Figure 1 simply because the ear canal is not straight.

Figure 6. Drawing depicting how the new EASYWEAR alters and locks the angle of the receiver into the ear canal.

The combination of the lateral connection and the angled earwire places the receiver in a position that essentially locks it to the wall of the ear canal—just medial to and behind the tragus. The resulting alteration of the angle of the receiver in the ear canal is shown in Figure 6. Despite these physical changes in the new wired receiver, all electroacoustic measures (frequency response, distortion, OSPL 90, maximum gain, etc) are equivalent to the previous Widex “standard” receiver.

Study Methods

Having established that cosmetic gaps and lateral migration are truly a significant clinical problem, a multisite investigation was performed in order to determine whether there is an improvement in physical fit and appearance (in terms of less lateral migration and fewer cosmetic gaps, respectively) for the new EASYWEAR from the subjects’ perspective, as well as from the HHPs’ perspective.

Current adult hearing aid users (minimum of 2 months’ hearing aid use with open fit) who reported lateral migration or cosmetic gaps during their clinical care were recruited from database records from four hearing care clinics in New York and Florida. A total of 34 subjects participated in the experiment and were reimbursed $25 for their involvement.

Subjects were divided into two groups: Group 1 consisted of 22 current Widex RIC users, and Group 2 was comprised of 12 non-Widex RIC users. Both groups were equivalent in terms of mean age (70.0 and 72.4) and years of hearing aid experience (4.0 and 3.8). Current Widex RIC users (Group 1) were instructed to evaluate the physical fit of their own RIC hearing aids and the new Widex EASYWEAR via a survey with questions addressing physical fit, stability, lateral migration, itching, appearance (lack of cosmetic gaps), and overall impression. For verification purposes, they also were provided with a manual counter and were instructed to click the counter every time they felt the need to push the receiver back into their ear canal over a 3-day period. They returned to the clinic 3 days later with their completed survey and manual counter data.

Because it would have been impossible to control for any sound quality bias for the non-Widex RIC subjects (Group 2), they were not given the EASYWEAR to wear outside of the clinic, thus they only evaluated their own non-Widex RICs. Two HHPs were involved in the experiment at each clinical research site. Subjects’ evaluation and manual counter data were given to the first HHP (the control HHP). The control HHP then left the room and was replaced by a second HHP (the evaluating HHP) who was not told which devices were being worn. The evaluating HHP then assessed the physical fit and appearance of the devices while standing in front of the subject, so as to not be able to determine whether the subject was wearing their own device or the new Widex EASYWEAR.

In addition, subjects were asked to describe the situations under which they encountered lateral migration and to attempt to force lateral migration when possible, by moving the jaw, chewing, wriggling the ears, etc. The evaluating HHP then left the room and the control HHP returned, assembled the new EASYWEAR to the Group 1 subjects’ own devices and placed the hearing aids in the ears before departing. Group 1 users were again instructed by the first HHP to repeat the 3-day trial, wearing the EASYWEAR and using the manual counter whenever migration occurred. Group 2 subjects were not given the EASYWEAR to wear outside of the clinic, thus they only evaluated their own devices; however, their own devices and the EASYWEAR were assessed by the evaluating HHP during the same visit and all hearing aids were turned off during the HHP’s evaluation.

Thus, to summarize, Group 1 subjects evaluated their own Widex RIC (termed the “standard”) and the new EASYWEAR. Group 2 subjects evaluated only their own non-Widex hearing aids. The evaluating HHPs, however, evaluated both groups while wearing their own hearing aids, as well as while wearing the new Widex EASYWEAR.

Results

Figure 7. Mean scores for Subjects’ evaluation of physical fit, stability, lateral migration, appearance, and overall impression of the “standard” Widex RIC (Group 1), non-Widex RIC (Group 2), and the new Widex EASYWEAR (Group 1). Bars represent standard error. All differences between the EASYWEAR versus either the standard Widex RIC or the non-Widex RIC, with the exception of Appearance, are statistically significant (p<0.05).

Subject evaluation. The information collected on the subjects’ surveys was collected for each ear individually. Since there were no significant differences between the ears, the results are combined. The data shown in Figure 7 were obtained using a Likert scale (0 to 10 with 10 representing the best response and 0 indicating the worst response). A related sample Wilcoxon Signed Rank test revealed statistically significant (p<0.05) preferences for the new EASYWEAR over either the standard Widex RIC or the non-Widex RICs for physical fit, stability, lateral migration, itching, and overall impression of the new wired Widex RIC. The rating of appearance, while considered superior for the new solution, was not statistically significant.

There were, however, no significant differences between scores for the non-Widex RIC (Group 2) and the standard Widex RIC (Group 1). Furthermore, the scores for the Widex EASYWEAR compared to the scores for the non-Widex RIC are statistically significant (p<0.001). The subjective impressions were further verified by the manual counter data obtained for Group 1 subjects comparing the standard Widex RIC to the EASYWEAR. The mean number of migration occurrences reported when using the standard Widex RIC was 15, but was only 2 for the new EASYWEAR. These differences were statistically significant (p=<0.001).

Figure 8. Mean values for the HHP’s evaluations of the Group 1 standard Widex RIC vs the EASYWEAR and Group 2 non-Widex RIC, vs EASYWEAR. Physical fit is shown in the left side graph and Appearance is shown on the right. Bars represent standard error. There are no significant differences between the standard Widex RIC versus the non-Widex RIC, but differences between the EASYWEAR versus the other RICs were significant for both Groups 1 and 2 (p<0.05).

HHP evaluation. Figure 8 shows the mean scores as assessed by the HHPs. A related sample Wilcoxon Signed Rank test revealed statistically significant (p<0.05) preferences for the EASYWEAR over both the “standard” Widex RIC and the non-Widex RIC for both physical fit and appearance (the only domains assessed by the HHPs). Once again, there were no significant differences between scores for the non-Widex RIC versus the “standard” Widex RIC.

Furthermore, the HHP asked all subjects to attempt forced lateral migration with their own hearing aids and with the new EASYWEAR. A total of 26 subjects (19 of 22 subjects in Group 1, and 7 of 12 subjects in Group 2) could force lateral migration while wearing their own non-Widex RIC or the “standard” Widex RIC. However, only 2 subjects (both from Group 1) could provoke it with the new EASYWEAR.

Summary and Conclusions

The trend toward increased use of mini BTE RICs is not likely to diminish. Yet, clinical experience, as well as the data collected in the survey on prevalence of lateral migration and cosmetic gaps, plainly indicate that these are genuine problems.

This situation is somewhat comparable to what the industry faced approximately 15 years ago when users demanded more devices in the canal, but the presence of cerumen and other debris in the receivers created frequent breakdowns and need for repair. The solution then—in the form of the Ceru-stop—appeared to be a seemingly small improvement in the world of wax guards, yet it became an enhancement that considerably improved the daily life of HHPs and hearing aid users.

Just as no user of hearing aids should have to encounter frequent breakdowns because of cerumen and other debris clogging a receiver, no user of present day RIC hearing aids should have to tolerate lateral migration and cosmetic gaps. Users do not want to have to frequently push their hearing aids back into their ears, as it is a nuisance and potential embarrassment. Similarly, HHPs do not want to have to schedule additional appointments to adjust the physical fit of the devices, as this is cost inefficient, or, worse, have to inform users that despite their desire for cosmetic “transparency,” this is the best that can be done.

Both the subjects’ and the HHPs’ data indicate that, while there were no apparent differences between the standard Widex RICs and the non-Widex RICs, there is a clear statistically significant preference for the new patented Widex EASYWEAR solution over either non-Widex RICs or the previous standard Widex RIC. This new solution restores synergy to the shape and connection properties of the earwire to that of the ear canal, minimizing the occurrences of lateral migration and cosmetic gaps.

Disclosure

Robert Sweetow, PhD, is a part-time consultant for Widex A/S.

References

1. Strom K. Hearing aid sales flat in first quarter; Wireless 70% of market. Hearing Review. 2013;20(5):6. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2013/05/staff-standpoing-hearing-aid-sales-flat-in-first-quarter-wireless-70-of-market

2. Morla A. Four transformative patient demands: convenience, size, simplicity, and flexibility. Hearing Review. 2011;18(4):36-42. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2011/04/four-transformative-patient-demands-convenience-size-simplicity-and-flexibility

3. Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: Consumer satisfaction with hearing aids is improving. Hear Jour. 2010;63(1):19-32.

4. Alvord L, Farmer B. Anatomy and orientation of the human external ear. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(6):383-390.

5. Oliveira R. The active ear canal. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(6)[Dec]:401-410.

6. Oliveira R. The dynamic ear canal. In: Ballachanda B, ed. The Human Ear Canal. San Diego: Singular Publishing Group; 1995:83-112.

7. Oliveira R, Babcock M, Venem M, Hoeker G, Parish B, Kolpe V. The dynamic ear canal and its implications. Hearing Review. 2005;12(2):18-19,82. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2005/02/the-dynamic-ear-canal-and-its-implications.

Robert W. Sweetow, PhD, is a professor at the University of California San Francisco; Sueli A. Caporali, PhD, is a research audiologist at Widex A/S in Lynge, Denmark; Patricia M. Ramos, AuD, is director of Audiology and Rehabilitative Services at ENT Associates of South Florida in Boca Raton, Fla; Cathi Ahrens Berke, BC-HIS, is a hearing instrument specialist at Ahrens Hearing Center in Fair Lawn, NJ; and Ellen Finkelstein, AuD, is chief audiologist at Eastside Audiology in New York City.

Original citation for this article: Sweetow, RW, Caporali, S, Ramos, PM, Ahrens-Berke, C, Finkelstein, E. A solution for lateral migration and cosmetic gaps in RIC hearing aids. Hearing Review. 2014;21(5): 18-23.