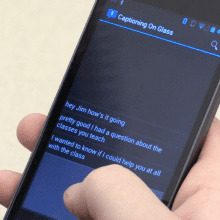

A captioning system designed for Google Glass allows a person to speak into a smartphone, and the text is displayed as a caption for a hard-of-hearing user.

A team of researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology has created speech-to-text software for Google Glass that helps hard-of-hearing users with everyday conversations. According to the research team that designed the Captioning on Glass software system, a hard-of-hearing person wears Glass while a second person speaks directly into a smartphone. The speech is converted to text, sent to Glass and displayed on its heads-up display.

A group in Georgia Tech’s College of Computing created the Glassware after their colleague, School of Interactive Computing Professor Jim Foley, said he was having trouble hearing and thought Glass could help him.

“This system allows wearers like me to focus on the speaker’s lips and facial gestures,” said Foley. “If hard-of-hearing people [like me] understand the speech, the conversation can continue immediately without waiting for the caption. However, if I miss a word, I can glance at the transcription, get the word or two I need and get back into the conversation.”

Smartphones Used with Google Glass Provide Additional Benefits

Foley’s colleague, Professor Thad Starner, leads the Contextual Computing Group working on the project. He says using a smartphone with Glass has several benefits as compared to using Glass by itself.

“Glass has its own microphone, but it’s designed for the wearer,” said Starner, who is also a technical lead for Glass. “The mobile phone puts a microphone directly next to the speaker’s mouth, reducing background noise and helping to eliminate errors.”

Starner says the phone-to-Glass system is helpful because speakers are more likely to construct their sentences more clearly, avoiding “uhs” and “ums.” However, if captioning errors are sent to Glass, the smartphone software also allows the speaker to edit the mistakes, sending the changes to the person wearing the device.

“The smartphone uses the Android transcription API to convert the audio to text,” said Jay Zuerndorfer, the Georgia Tech computer science graduate student who developed the software. “The text is then streamed to Glass in real time.”

Captioning on Glass is currently available to install from MyGlass. More information and support can be found at the project website. Foley and the students are working with the Association of Late Deafened Adults in Atlanta to improve the program.

The same group is also working on a second project, Translation on Glass, that uses the same smartphone-Glass Bluetooth connection process to capture sentences spoken into the smartphone, translate them to another language and send them to Glass. The only difference is that the person wearing Glass, after reading the translation, can reply. The response is translated back to the original language on the smartphone. Two-way translations are currently available for English, Spanish, French, Russian, Korean and Japanese.

“For both uses, the person wearing Glass has to hand their smartphone to someone else to begin a conversation,” said Starner. “It’s not ideal for strangers, but we designed the program to be used among friends, trusted acquaintances or while making purchases.”

The group is working to get Translation on Glass ready for the public.

Source: Georgia Institute of Technology, School of Interactive Computing and Contextual Computing Group