Research | December 2014 Hearing Review

Value-based reimbursement in medicine has huge implications for hearing healthcare.

This is the third part in a series of articles on the topic of interventional audiology. In Part 1 (November 2013 Hearing Review),1 we pointed out that, rather than centering on the dispensing of a hearing aid or medical device, we should be practicing interventional audiology: a focus on the disease state of hearing loss and its relationship to the chronic medical consequences of hearing loss. In Part 2 (July 2014 HR),2 we explored some of the specific research that directly encourages the medical-audiological relationship and how to leverage peer-reviewed health science to build a physician referral base. In Part 3, we link the changes in healthcare and our emerging knowledge of behavioral models of hearing loss with in-clinic success.

Patient Communication as a Basic Healthcare Problem

Let’s begin with an all too common situation, which until rather recently has been unreported in the literature: An individual in his early 70s with Type II diabetes and mild, sensorineural hearing loss delays medical care because he hesitates to call for an appointment with his primary care provider due to difficulty understanding the appointment clerk on the phone. Once he finally calls, the patient misunderstands the instructions he is given. Thinking he has been told to alter his medication regimen, his diabetes is soon out of control and he ends up in the emergency room. Such patients are perhaps more common than we realize, and as recent research suggests, mild-to-moderate age-related hearing loss (ARHL) can contribute to poor health in many ways—including delaying appropriate care as well as being a cause of poor patient compliance due to unintended miscommunication.

Changing medical priorities and reimbursement. There is a constellation of forces at work within the American healthcare system that may enable hearing care professionals to emerge as integral members of a patient’s health and wellness team. The graying of the American population, the notion that baby-boomers want more active participation in their healthcare, the emergence of direct-to-consumer amplification products, the unsustainably rising costs of healthcare—all of these factors have the potential to profoundly change the way audiology and hearing care are perceived by primary care physicians.

Primary care in the United States is changing. Both private and public insurance programs, as well as large employers, are changing the way primary care providers are being reimbursed for their services. The reason for these changes is the rising cost of healthcare and the realization that primary care is the key to reducing those costs.

The focus of the change is that “value” payments are being added to the traditional “volume” based fee-for-service reimbursement system in primary care. Reimbursement in traditional primary care is a function of volume: the more patient visits a primary care practice sees in a year, the higher the annual revenue will be. The system is complex in that some patient visits receive higher reimbursement than do others, but the system has nevertheless been purely volume-based.

As a result, the efficiency of the primary care office is key. The focus is on seeing the maximum number of patients a day that can reasonably be accommodated with the minimum of overhead expenses. The most successful practices in this traditional volume-based model were usually the busiest. Acutely ill patients were seen promptly, but other patients waited patiently, sometimes for many days and even weeks for routine appointments.

Over the last decade or two, it has been recognized that this traditional system has a very significant unintended consequence. Primarily because of delays in care, patients became sicker. When they finally had their appointment, they needed more care than would have been the case if they had been seen sooner. As a result, the value of the care was less than what it could have been. Volume was consistently trumping value.

There were other problems as well. If patients were not sufficiently motivated to take care of their health, they would often miss recommended screening tests or take medicines irregularly. As a result, they suffered from illnesses that could have been avoided, and caring for those illnesses was yet another cost to the healthcare system. That cost is large, and it turns out that paying primary care to focus more attention on prevention and earlier treatment is far less expensive that paying the entire healthcare system for the cost of caring for patients who had missed opportunities to detect, prevent, or treat illnesses at an earlier stage.

Modifying payment systems for a value emphasis. There are many ways being used today to pay primary care practices to improve the value of their services. One common method is to pay the primary care practice a periodic bonus if certain performance standards—usually called “Quality Metrics”—are met. A common quality metric in primary care today focuses on the care of diabetic patients: if lab and other tests done to measure the effectiveness of diabetic treatment meet certain standards, the primary care practice receives periodic cash payment from the insurer based on the number of diabetics in their practice and the quality measure performance. This payment is in addition to the usual volume based reimbursement which the practice receives for each visit.

There are numerous quality metrics being applied to primary care practices today, though the specific value-based payment varies by insurer and location. These payments tend to focus on the quality of care for chronic diseases and also on the percent of patients who receive preventive treatments (eg, vaccinations) or screenings (cancer, cholesterol, etc). The number and sophistication of these quality metrics is rapidly increasing, and as this occurs, the potential dollar value of the payments to the practice is also increasing.

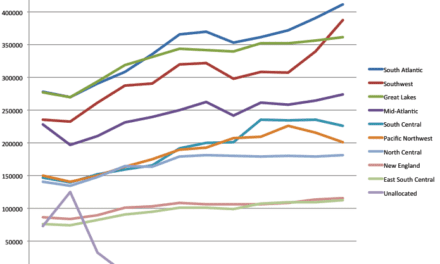

Only a few years ago, most primary care practices had little or no opportunity to receive revenue on the basis of quality metric performance. Today, almost all traditional primary care practices are eligible for such payments. It is not uncommon for practices to receive an additional 10% of their annual revenue from quality metric performance; and 20% and even 30% of traditional volume-based revenue are being seen from high performing practices. Recent announcements by Medicare suggest this trend will continue.

The “new money” for primary care actually represents a transfer of money from hospitals and specialists. The key concept is right care, right provider, right place, right time. If primary care provides patients with “right care/provider/place/time,” then the patient will need fewer hospitalizations, fewer ER visits, and fewer specialty referrals.

The language being used to capture this idea is that primary care is doing population health. Hospitals and specialists, naturally, are having trouble accepting the fact that this idea has gained traction with insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid. But it has gained traction because it works. The increase in income to primary care is only a small fraction of the decrease in income to hospitals and specialists, and the savings in healthcare costs for large employers, insurers, and government programs is why this is going to grow.

What Does This Mean for Hearing Healthcare?

Referrals to audiology and hearing care professionals from primary care in the past were generated for the most part by requests from the patient and their family. Treatment of hearing loss was considered elective, an issue that was almost entirely related to patient preference.

Today, if hearing loss is recognized as a factor leading to poor patient compliance with medical care, then the poor compliance will cost the physicians’ practice real money. This makes a difference in how hearing loss is viewed by the primary care physician.

In the traditional reimbursement environment, primary care providers are not at financial risk if their patients do not take their medicine, do not have recommended vaccinations or screening tests, or do not follow up after they are seen by another doctor. With value-based reimbursement systems growing rapidly, these same primary care practices are now at a clear financial risk. And that financial risk is large enough that they are paying attention.

The evidence is growing that hearing loss—even mild to moderate hearing loss (see Barbara Timmer’s article3 in the April 2014 Hearing Review)—interferes with communication and speech understanding at a very basic level. This communication and understanding is critically important for patient compliance with medical care, especially for patients with chronic illnesses and the elderly. And, of course, these are the very patients who have the highest incidence of hearing loss.

Hearing healthcare has a new opportunity to become a partner with primary care providers because the hearing healthcare specialist can help the primary care provider succeed. Audiologists, in particular, should understand these new issues in primary care and be clear that the services which audiology offers are not simply services to the patient, but they represent a service that will help the primary care practice as well.

In short, interventional audiology can help primary care practices add value in a way that boosts their bottom line as well as improve the quality of life for many of their Baby-boomer patients.

It Starts With Education to PCPs

Clearly, hearing care professionals must leverage the changing healthcare system by working closely with primary care physicians and administrators so that a greater number of patients suffering from conditions associated with hearing loss come forward at an earlier age for hearing screening. Part of this strategy includes educating primary care medicine about the increased costs associated with caring for individuals with hearing loss.

Foley et al4 recently demonstrated that self-reported hearing loss is independently associated with higher total medical expenditures. In the population of individuals with self-reported hearing loss in the US population aged 65 and older in 2010 (7.91 million lives) indicates that hearing loss is associated with approximately $3.10 billion in excess total medical expenditures. Hearing loss was associated with greater odds of office-based, outpatient, and emergency department visits and not only costs that would be directly attributable to hearing loss treatment (eg, medical equipment expense). Future work should investigate the mechanistic basis of the observed association and whether public health strategies focused on hearing rehabilitative treatment could mitigate excess medical expenditures associated with hearing loss.

Future hearing healthcare marketing strategies need to focus on how to integrate the “knowledge economy” to generate tangible and intangible values in the primary care market place. The key component of a “knowledge economy” is a greater reliance on intellectual capabilities.

Unfortunately, hearing care’s marketing focus has been primarily based on technology. A transition to marketing our knowledge of modifiable risk factors that contribute to the presence of co-morbidities, resulting in an increased risk and incidence of hearing loss is vital to the future of hearing healthcare. We should implement an “Educate to Obligate” marketing strategy aimed squarely at primary care physicians, utilizing clinical research, changing healthcare economics, patient education, and services-focused marketing that persuades them to think differently about how to enter into a patient care partnership with us.

This partnership can be entered into if audiologists and hearing care professionals change their roles to that of “interventionist” and “knowledge marketers” who inform primary care about how our expertise and services can assist in primary care’s ability to practice “preventive care.” Ultimately this partnership improves the quality of care, the quality of lives, and the quality of the financial performance of the primary care, as well as the hearing care practice.

In-Clinic Success and Help-Seeking Behavior Models

Even a partnership based on mutual respect between primary care medicine and the hearing care professions may not be enough to overcome the forces associated with the ambivalent patient who is often resistant to our interventions. Interventional audiology strategies are not confined only to marketing efforts. Recent reports have indicated that a recommendation for a hearing screening often does not prompt individuals to take action to resolve a suspected hearing problem.5

This inability to take swift action can be explained through the lens of help-seeking behavior. Over the past few years, several studies have enriched our knowledge of how adults with chronic medical conditions, such as ARHL, manage their condition and what cues to action may influence their behavior change. Various models have been proposed to explain the process of coping with chronic conditions, some of which have been applied to ARHL.

Transtheoretical Stages of Change model. The Transtheoretical Stages of Change model (Figure 1) has been used to describe how adults with hearing loss cope with their condition.6 The “stages of change” model suggests that an individual’s ability to change passes through four distinct levels. These levels are best summarized as:1) Pre-contemplation, at which time the individual cannot even consider acknowledging a problem exists and that behavior change is needed;

2) Contemplation, at which time individuals are ambivalent about the existence of a problem and the need to change behaviors;

3) Preparation, at which time an individual is preparing to make changes by seeking information and talking about this possible change with others;

4) Action, during which time individuals make actual changes to their behaviors.

5) Maintenance, when the individual makes a deliberate attempt to maintain their changed behaviors.

Two self-report questionnaires have been used in “stages of change” research to ascertain the underlying decision making process of individuals with hearing loss. The Health Belief Questionnaire (HBQ)7 is a 33-item assessment, developed by Saunders and colleagues that measures five constructs: severity, benefits, barriers, self-efficacy, and cues to action on a 10-point scale. A summary of the five constructs comprising the Health Belief Model is shown in Figure 2. Additionally, the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA)8 is a 24-item self-report assessing the first four stages of change outlined in Figure 1, using a 5-point scale. Although both tools have been validated, given their length, neither questionnaire is considered viable clinical tools in their current form.

Research using the Health Belief Model and Stages of Change model have attempted to better understand behaviors of individuals with hearing impairment who have failed hearing screening. Milstein and Weinstein9 evaluated the “stage of change” in 147 older adults participating in hearing screening. Before the screening, 76% of the participants were in the precontemplative or contemplative stages. Stages-of-change scores did not significantly change as a result of the screening.

More recently, Laplante-Levesque et al10 evaluated the stage of change of 224 adults who failed an online hearing screening. In this study, 50% of the participants were in the preparation stage of change, while 38% were represented by the contemplation stage and another 9% by the precontemplation stage. Only 3% of the participants were in the action stage.

Taken as a whole these studies suggest that hearing screening alone is not enough to improve help-seeking rates. Clearly, there are opportunities beyond the offering of an easy-to-use automated or online hearing screening tool that must be considered if our profession is to improve our acceptance rates.

The Spiral of Decision Making model. Another line of research attempting to explain the underlying decision-making process of hearing-impaired individuals was proposed by Carson.11 The Spiral of Decision Making model (Figure 3) explains the “push-pull” between seeking and not seeking help that many patients with hearing loss of gradual onset experience.

Carson based her Spiral of Decision Making model on the longitudinal study of a group of woman between the ages of 72 and 82 years of age. Her model suggests that individuals with gradual hearing loss evaluate, analyze, and make decisions around three themes that define self-assessment: “comparing/contrasting,” “cost vs benefit,” and “control.” Carson’s model proposes that this spiral of decision-making is ongoing, even after remediation for hearing loss has begun.

Changes in the primary care delivery model and implementation of knowledge-based marketing tactics intended to foster a deeper relationship between audiologists and physicians do not alter the fact that onset of hearing loss in adults is a stigmatizing condition. In order to embrace the health belief models shown in Figures 1-3, hearing care professionals are encouraged to view the condition of ARHL through the lens of the social model of disability. Given the ambivalence of all stakeholders—patients, families, physicians, etc—toward onset of hearing loss in adults, the social model of disability (Figure 4) is the common thread tying together the concepts discussed in this article

The social model of disability identifies systemic barriers, negative attitudes, and exclusion by society for individuals suffering from a chronic condition, such as ARHL. While physical, sensory, intellectual, or psychological variations may cause individual functional limitation or impairments, these do not have to lead to disability unless society fails to take account of and include people regardless of their individual differences.

In an evolving healthcare system, the role of physicians, audiologists, hearing instrument specialists, and others is to ease, reduce, or eliminate environmental, attitudinal, and societal barriers of patients.

Summary

1) The way primary care medicine is practiced is changing and this change affords hearing care professionals an opportunity to get more directly involved in the care of patients at younger ages with milder hearing loss.

2) If hearing care professionals are to leverage these opportunities they must use evidence from peer reviewed studies, which shows a relationship between various medical conditions and ARHL as a key part of their marketing message. This change requires a significant shift away from price-driven , product-centric advertising to knowledge-based marketing strategies, which place the skills of the practitioner at the center.

3) Given the psychological nature of ARHL, long-term professional success is largely predicated on what happens once a patient decides to seek the services of a practitioner. The essence of the practitioners skills rests with their ability to unravel the so-called spiral of decision making. Ultimately, it is the personal relationship between hearing care professional and primary care physician; hearing care professional and patient that drives the sustainability of the our profession. Viewing our value proposition through the lens of the social model of disability, rather than through the lens of the medical model of disability in which the dispensing of hearing aids is at the center, has the potential to transcend the marketplace. The next installment of our interventional audiology series will examine the role of solution-based interviewing techniques and how they can be used to improve in-clinic success.

References

References

1. Taylor B, Tysoe B. Interventional Audiology: Partnering with physicians to deliver integrative and preventive hearing care. Hearing Review. 2013;20(12):16-22. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2013/11/interventional-audiology-partnering-with-physicians-to-deliver-integrative-and-preventive-hearing-care2

2. Taylor B, Tysoe B. Forming strategic alliances with primary care medicine: interventional audiology in practice: How to leverage peer-reviewed health science to build a physician referral base. Hearing Review. 2014;21(7):22-27. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2014/06/forming-strategic-alliances-primary-care-medicine-interventional-audiology-practice

3. Timmer B. It may be mild, slight, or minimal, but it’s not insignificant. Hearing Review. 2014;21(4):30-33. Available at: https://hearingreview.com/2014/04/may-mild-slight-minimal-insignificant

4. Foley D et al. Association between hearing loss and healthcare expenditures in plder adults. J Am Ger Soc. 2014;62(6):1188-1189.

5. Pacala JT, Yueh B. Hearing deficits in the older patient: I didn’t notice anything. JAMA. 2012;307(11):1185-1194.

6. Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997 Sep-Oct;12(1):38-48.

7. Saunders G, et al. Application of the Health Belief Model: Development of the Health Belief Questionnaire (HBQ) and its association with hearing health behaviors. Int J Audiol. 2013;52:558-567.

8. McConnaughy J, et al. Stages of change in psychotherapy: Measurement and sample profiles. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1983;20:268-376.

9. Milstein D, Weinstein BE. Effects of information sharing on follow-up after screening for older adults. J Acad Rehab Audiol. 2002;35:43-58. Available at: http://www.audrehab.org/jara/2002/Milstein%20Weinstein,%20%20JARA,%20%202002.pdf

10. Laplante-Lévesque A, Brännström KJ, Ingo E, Andersson G, Lunner T. Stages of change in adults who have failed an online hearing screening. Ear Hear. 2014; Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25158981

11. Carson, A. (2005). “What brings you here today?” The role of self-assessment in help-seeking for age-related hearing loss. J Aging Studies. 2005;19:185-200.

12. Goodley D. “Learning difficulties”, the social model of disability and impairment: challenging epistemologies. Disability & Society. 2001;16(2): 207-231.

CORRESPONDENCE can be addressed to Dr Taylor at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Taylor B, Tysoe B. Forming strategic alliances with primary care medicine: interventional audiology in practice: How to leverage peer-reviewed health science to build a physician referral base. Hearing Review. 2014;21(7):22-27.