Back to Basics | May 2015 Hearing Review

Naomi Croghan, along with her PhD supervisors and now colleagues, Kathryn Arehart and James Kates, has recently published an article in Ear and Hearing entitled “Music Preferences With Hearing Aids: Effects of Signal Properties, Compression Settings, and Listener Characteristics.” In the study, they used a virtual hearing aid where music could be processed through 3 channels vs 18 channels, and with a short release time (50 msec) and a long release time (1,000 msec). Classical and rock music were piped through these various processing strategies and played to 18 experienced hearing aid users.

Their research showed that the 1,000-msec release time was perceived as being better than the shorter 50-msec release time. This can be summarized under the rule of thumb that “less change is more.” Improved perception of music (and undoubtedly speech) is obtained by either staying in a linear mode or staying in a WDRC mode for most of the time; switching back and forth may be problematic.

Along with studying the effects of release time on WDRC, the authors also looked at the number of frequency channels for the two types of music being studied. In this virtual (or simulated) hearing aid study, perception of classical and rock music was assessed in 18 experienced hearing aid wearers where the hearing aid was set for 3 channels and for 18 channels.

The study found, “For classical music… [the] number of channels was not significant. For rock music…three channels were preferred to 18 channels.”

I wonder if they would have found the same results if there had been an option of only one channel. Here are my thoughts.

Classical vs Rock

Classical music has several salient differences from rock music: there are spectral differences, but, depending on the selection of the rock piece and the classical piece, this issue is highly variable, and I would be unable to conclude how one spectrum might differ from the other. However, there is a major difference in the size and number of string instrument players in a classical orchestra versus that of a typical rock band. A classical orchestra has violins, violas, cellos, and basses—as many as 30+ string players. A rock band may have one violin as a “curiosity,” but it is certainly not “string-heavy.”

A string musician perceptively looks for different things than a woodwind player, a guitarist, or a drummer. When I, as a clarinet player, say, “That’s a great sound,” I am referring to the lower frequency inter-resonant breathiness of my clarinet. Even though my clarinet can generate significant high-frequency energy, I don’t need to hear it to make a judgment of the quality of my playing. A clarinet is a wonderful instrument for people with a (congenital or acquired) high-frequency hearing loss—I just need to hear up to 1,000 Hz, and I’m fine.

In contrast, when a violinist says, “This is a great sound,” or we as listeners judge a certain violin as a wonderful sound versus that of a student model, we are making a judgment based on the relative magnitudes of the fundamental (or tonic) and higher frequency harmonics and overtones of the instrument. Hearing the violin at 4,000 Hz and relating this sound to its fundamental at 262 Hz (middle C) gives us a judgment of music beauty. For string players, judgments of this sort are broadband, whereas for woodwinds they tend to be more restricted in required bandwidth.

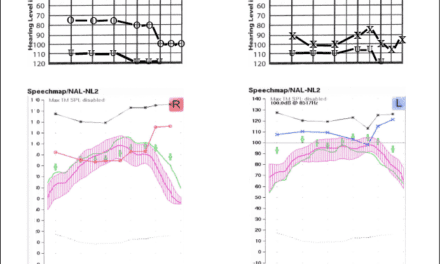

Consider a 3-channel hearing aid (simulated or real) where the fundamental at middle C is at 262 Hz and the fifth harmonic is at 1,572 Hz (6 x 262 Hz); the fundamental may be in the lowest frequency channel (perhaps 200-800 Hz); the fifth or so harmonic is in another separate channel (perhaps 800-2,000 Hz); and the upper frequency components of the violin are in the top-most channel (perhaps 2,000-7,000 Hz).

In this scenario, the fundamental (or tonic) is compressed differently from that of the harmonic structure in Channel 2, and also differently from the harmonics in Channel 3. In multi-channel processing, the magnitude of the lower frequency fundamental at 262 Hz may end up having no relation to the magnitude of the higher frequency harmonics that are in different channels. The important balance between frequency components can be lost.

Compare this now with a single 1-channel hearing aid (no longer commercially available, but can be simulated on a virtual hearing aid). In this scenario, the relative magnitude of the lower frequency fundamental is treated identically to the 10th or 20th harmonic and the balance is maintained. It could be that the processed classical music with “only” 3 channels was already significantly degraded (with anything more, such as 18 channels already being perceived as asymptotically poor quality).

A Single-channel Program for Music?

Croghan et al’s finding that the “number of channels was not significant. For rock music… three channels were preferred to 18 channels” could perhaps have been more clearly stated as “For classical music, anything greater than a single channel would be lousy.” I’m sure that they would not have said “lousy” but I would. Personally, I have listened to music through single-channel hearing aids (such as the 1988 K-AMP from Etymotic Research) and they sound great for music, as opposed to more modern digital hearing aids, even when listened to at a quiet playing level.

I also wonder if, even for Rock music, a single channel would be better than the simulated 3-channel system? Again, we may find that less may be more.

The hearing aid industry does need to create a single-channel hearing aid for music, or at least a music program in the hearing aid that truly functions as a single-channel device. There is little doubt that multi-channel processing has major benefits for speech—especially in noise—but I believe that it was an error to extend this lesson from speech to the processing of music.

Marshall Chasin, AuD, is an audiologist and director of research at the Musicians’ Clinics of Canada, Toronto. He has authored five books, including Hearing Loss in Musicians, The CIC Handbook, and Noise Control—A Primer, and serves on the editorial advisory board of HR. Dr Chasin has guest-edited three special editions of HR on music and hearing loss (August 2014, March 2006, and February 2009), as well as a special edition on hearing conservation (March 2008).

Correspondence can be addressed to Dr Chasin at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Chasin, M. Less May Be More for Music. Hearing Review. 2015;22(5):14.

Adapted with permission from Dr Chasin’s November 25, 2014 blog at http://hearinghealthmatters.org/hearthemusic