Letters | OTC Hearing Aids

Dear Editor:

I read the article “Evaluating Select Personal Sound Amplifiers and a Consumer-Decision Model for OTC Amplification” by Ron Leavitt, Ruth Bentler, and Carol Flexer1 in the December 2018 issue of Hearing Review with great interest. Many researchers, clinicians, and consumers are keenly interested in research regarding “over-the-counter hearing aids” (OTC HAs). A key focus of the article by Leavitt et al is the severity of pure-tone hearing loss in our earlier work2 (which was summarized in a June 2017 HR article3) and the “limitation” that most of our participants had “mild” pure-tone hearing loss. The research by Leavitt and colleagues, however, is presented in the broader context of the OTC Hearing Aid Act and the initiatives leading to its adoption into law in late 2017. Part of this broader context is that there are millions of adults—mostly older adults—who have hearing loss that could benefit from amplification but who never seek help or purchase hearing aids. It has often been noted that roughly 20% of those who could benefit from hearing aids actually seek them out and purchase them, and this has been the case for many years in the United States (and elsewhere).

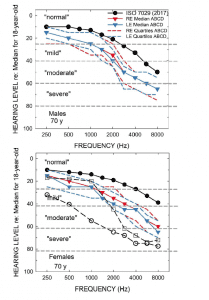

Figure 1 [click on images to enlarge]. Audiometric data in Humes et al 2017 study.2 The bottom panel includes the mean audiogram from Leavitt et al,1 and both panels include the WHO classifications for severity of hearing impairment.5

Several important observations can be drawn from the data in Figure 1. First, pertaining to the ISO standard values (filled circles), the medians for 70-year-olds were selected because the mean age for the ABCD participants in our study, for both males (top) and females (bottom), was 69.1 years. The ISO medians come from a compilation of many studies of age-related hearing loss for screened samples, not the general population. Note that it could be argued that even the average 70-year-old male or female from such screened samples has “mild-to-moderate” hearing loss in the high frequencies. The color-coded blue and red data from our prior study2 show even greater hearing loss than the “average” 70-year old male or female. The hearing loss depicted for the ABCD participants from our lab could be accurately categorized as “mild-to-moderate sloping hearing loss.”

Importantly, by design, all the participants in our study were new hearing aid users. Further, most of those 70-year-olds represented by the ISO medians were unlikely to have used hearing aids, based on the low market penetration noted previously. Thus, audiograms like these, not those in Leavitt et al,1 are representative of the 80% who have measurable hearing loss but choose not to seek help or hearing aids. It is exactly this group that has been the focus of the movement to improve the accessibility and affordability of hearing healthcare and the impetus behind the OTC Hearing Aid Act.

By contrast, the unfilled circles in the bottom panel show the mean pure-tone thresholds for the 6 participants (3 male, 3 female) in Leavitt et al. Clearly, the hearing loss is considerably greater in those six individuals (mean age of 60.5) than the average 70-year old, as well as the participants in our prior study. Critically, all 6 were reported to have been previous hearing aid wearers with 0-25 years of experience (mean of 12.8 years). Clearly, the average hearing loss of the participants in Leavitt et al is considerably greater than in our study, but I’d argue that this is not the group targeted by the OTC HA Act. The six individuals in Leavitt et al were already wearing hearing aids, in several cases for many years, and “…all are working professionals who reported they depend on optimized hearing to perform in their respective professions.” Audiology and audiology best practices have served the 20% with more severe difficulties well for many years, including these six individuals, but this is not the target group for OTC devices. Rather, it is the other unserved 80%.

One could argue with the way in which I’ve chosen to characterize the hearing loss in our prior study as “mild-to-moderate” sloping hearing loss. Using the WHO’s definition5 of hearing impairment severity based on the four-frequency pure-tone average of the better ear, there is no question that most of our study participants fall in the “mild” hearing loss category, and many fall in the “normal” category, as noted by Leavitt and colleagues. Population studies in the United States and Australia, however, show that those meeting the WHO audiometrically defined “normal” and “mild” hearing-impairment grades represent about 65% and 25% of the adults over age 50 years, respectively (Humes 2018, in press). These individuals represent the most likely pool of first-time hearing aid users—again, the segment of the older population targeted by the OTC Hearing Aid Act.

Critically, the OTC Hearing Aid Act defines the target group as follows: “adults over the age of 18… [with] perceived mild to moderate hearing impairment.” That is, the target group is not required to meet an audiometric definition of “mild,” “moderate,” or “mild-to-moderate.” If an individual perceives that he or she is having difficulty hearing, an OTC HA can be pursued as a remedy. An audiometric definition of the severity of the impairment is not required.

Figure 2. Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE) scores for participants in the Humes et al2 and Humes (in press) studies showing hearing aid benefit for normal, mild, and moderate hearing losses per the WHO hearing-impairment classification system.

As shown in Figure 2, many older adults with audiometrically defined “normal” hearing have perceived hearing difficulties as measured by the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly screening (HHIE-S) tool.6 The participants in both of our published clinical trials clearly had a perceived hearing impairment, sufficient to have sought help through voluntary enrollment in a clinical trial in response to a newspaper ad.

Figure 3. Pooled data for participants in the from Humes et al2 and Humes (in press) studies showing hearing aid benefit for normal, mild, and moderate hearing losses per the WHO hearing-impairment classification system.

It is also the case that those with “normal” hearing, based on the WHO hearing impairment scale, can benefit from hearing aids if their perceived need is sufficient.7 Figure 3 shows data pooled from our two clinical trials (Humes et al 20172 and Humes et al, in press). Outcomes for self-reported (perceived) hearing handicap, HHIE, are shown for 194 total participants; all first-time hearing aid users. Of these, the majority (61%) are “mild,” but there are many (21%) with “normal” hearing per the WHO hearing impairment definition. Yet, all three groups show significant and similar hearing aid benefit in terms of reduction in the perceived hearing handicap. Thus, it would be inappropriate to restrict candidacy for OTC amplification to some audiometrically defined criterion. Rather, consumers who perceive the need for help should be able to access such help independently and affordably, whether the pure-tone audiogram supports a WHO-HI grade of “normal,” “mild,” or “moderate.”

Finally, comparison of the unfilled circles and unfilled squares in the lower panel of Figure 1 indicates that the hearing aid in the CD condition grossly underamplified speech, especially below 3000 Hz. It is little wonder that the CD condition showed low aided SII values and low benefit in behaviorally measured speech-in-noise performance in Leavitt et al1 given such underamplification. The audiograms used to program the hearing aids for the CD subjects in our study, including the most severe case represented by the unfilled squares in the lower panel of Figure 1 to which Leavitt et al programmed their CD hearing aid, were selected to be the most prevalent among the general population of older adults, the majority of whom have “normal” hearing audiometrically, as noted above. The range of CD audiograms used in our prior study were not intended to represent a range of hearing losses common to experienced hearing aid users as these users are not the targets for OTC hearing aids.

— Larry Humes, PhD

The authors respond: The main purpose of our article1 was to make a specific point. Regardless of the intended market, we know OTCs will be purchased by individuals with a wide range of hearing losses. Our goal was to clearly demonstrate that in many cases, a consumer decision model will result in a very inadequate fitting, much worse than what could be attained if audiologic best practices had been employed.

—Ron Leavitt, AuD, Ruth Bentler, PhD, and Carol Flexer PhD

References

-

Leavitt R, Bentler R, Flexer C. Evaluating select personal sound amplifiers and a consumer-decision model for OTC amplification. Hearing Review. 2018;25(12)[Dec]:10-16.

-

Humes LE, Rogers SE, Quigley TM, Main AK, Kinney DL, Herring C. The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Audiol. 2017;26(1):53-79.

-

Humes LE, Rogers SE, Quigley TM, Main AK, Kinney DL, Herring C. The effectiveness of two service-delivery models in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Hearing Review. 2017;24(5);12-19.

-

International Standards Organization (ISO). Acoustics — Statistical distribution of hearing thresholds related to age and gender. January 2017. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/42916.html

-

Mathers C, Smith A, Concha M. Global Burden of Hearing Loss. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO):1991.

-

Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the elderly: A new tool. Ear Hear. 1982;3(3):128-134.

-

Beck DL, Danhauer JL, Abrams HB, Atcherson SR, et al. Audiologic considerations for people with normal hearing sensitivity yet hearing difficulty and/or speech-in-noise problems. Hearing Review. 2018;25(10)[Oct]:28-38.

Larry E. Humes, PhD, is a Distinguished Professor of Speech & Hearing Sciences in the Department of Speech & Hearing Sciences at Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind.

Ron Leavitt, AuD, owns a practice in Corvalis, Ore, and is the Founder of the Oregon Assn for Better Hearing, a nonprofit consumer test group for hearing aid users; Ruth Bentler, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of Iowa, Iowa City; and Carol Flexer, PhD, is a Distinguished Professor of Audiology at the University of Akron.