Research | February 2018 Hearing Review online

This article describes how hearing-impaired persons and their partners experience and manage hearing loss in the context of their conjugal relationships. Based on in-depth interviews and being together with hearing-impaired persons and their partners, it argues that the social implications of hearing loss are associated with the temporal aspects of conversational exchange. A more nuanced understanding of the strategies hearing-impaired people and their partners employ to manage interactional complications can help to improve care and support for people affected by hearing loss.

Hearing loss is one of the most common chronic disabilities. A valid estimate is that 10 percent of the populations in the USA and Europe have some degree of hearing impairment.1,2 (Authors’ note: In the present article, we use the terms “hearing loss,” “hearing-impaired,” and “hard of hearing” interchangeably. Scholars and audiologists seldom account for the terms used. Some participants used the term “deaf” about their hearing loss or less frequently talked of having a “disability.”)

A number of scholars have described how hearing loss affects social interaction and social relationships, primarily through its impact on verbal communication and conversation.3,4 The goal of this article is to advance understanding of the social implications of hearing loss by analysing how hearing-impaired persons and their partners experience and manage hearing loss within the context of their conjugal relationships, as well as in the wider social context. Conjugal relationships refer to married persons and their relations and include cohabiting partners and couples.5 Scholars have pointed out certain shortcomings in the treatment of hearing-impaired persons linked to wider social factors of the hearing-impaired person’s family situation, what we refer to as the socio-sonic context. Audiologists and other health care professionals need to understand the social implications of hearing loss in assessing their patients’ or clients’ needs for health care, hearing care, and rehabilitation.6,7

The article begins by presenting our analytical framework and sources of inspiration. We then present our data and methodology. This is followed by a discussion of the frictions and frustrations that hearing loss may cause in conjugal relationships. We argue that these frictions and frustrations are closely related to the changes in the communication between partners—particularly the temporal aspects of conversational exchange. The following sections elaborate a broader socio-sonic context for understanding and interpreting hearing loss in conjugal relationships and address how the participants experience, manage, and navigate their hearing loss in noisy soundscapes. The article concludes with a discussion of the role of the hearing partner in mediating social situations.

Theorizing Hearing Loss: Analytical Considerations

A number of studies have explored the implications of hearing loss for hearing-impaired people and their close partners.3-8,10,13-17 The majority of these studies focus on the impact of hearing loss on close or intimate relationships, whether from the perspective of the hearing-impaired person, the partner, or both. On the whole, these studies show that hearing loss produces feelings of frustration, embarrassment, and distress for the partner and for the relationship in general.

These studies tend to focus on the immediate conjugal relationship and relegate the wider social relations to the background. It is these wider relations, which are of particular interest in the present article (see also Morgan-Jones3). More specifically, we argue that coping with hearing loss is basically about managing noise; that is, being able to pick out the relevant and sense-making sounds from irrelevant noise. What is relevant sound and what is relevant to hear, however, depends on the social context and situation. Managing noise, therefore, is not only a technical skill related to the fitting of the hearing aid; managing noise is also about navigating different soundscapes,18 defined here as the landscapes or surroundings represented by sounds20 and socialities.

Anthropologists consider conversation to be the cornerstone of social interaction and social life, a vehicle for exchanging, sharing, and constructing meaning, knowledge, and identities. (This does not mean, of course, that talk is the only component of interaction, or that conversation is talk’s sole form, even if it seems to be the most general one.22) Conversation and spoken interaction are subject to more-or-less explicit social and cultural rules, and may be regarded as particular forms of exchange and reciprocity. For instance, when a person says something to another person, he or she expects some kind of response within a certain time frame, depending on the situation and context.20 Turn-taking and closings in informal conversations are negotiated during the interaction, and usually, conversational exchanges run smoothly. Hearing loss, however, disturbs this smooth “give-and-take exchange.”4 The social situation is altered. Hence, we argue here that the social complications resulting from hearing loss affect the temporal aspects of conversational exchange. As Clayman points out:

“Spoken interaction, perhaps the fundamental locus of social interaction and organisation, depends on the ability of speakers-hearers to coordinate their actions temporally so as to produce talk that unfolds by turn with a minimum of gap and overlap” [p660, emphasis added].23

It is exactly this temporal coordination that becomes complicated, if not totally undermined, when conversation involves a person with hearing loss. The major challenge for hearing-impaired persons is that they often need to have things repeated, as well as need extra time to process and make sense of what they have heard.

Approaching Hearing Loss: Methodology

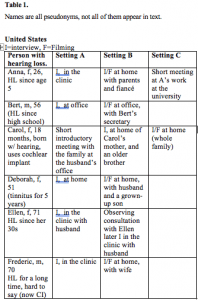

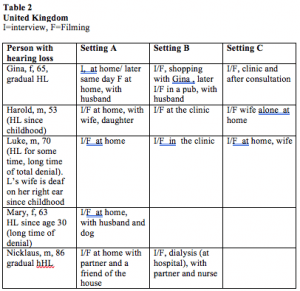

The data presented and analysed in this article are based primarily on ethnographic in-depth interviews with hearing-impaired persons and their partners and family members. In total, we included 11 persons with hearing difficulties and 18 partners, parents, and other relatives (see Tables 1 and 2). The study and the fieldwork took place in the state of Georgia (USA), over a 3-week period in September/October 2009, and in the UK over a 10-day period in October 2009. In most instances, the interviews took place in the participants’ homes, but we also interviewed participants at the clinics. In addition, we joined some participants for lunch, shopping, driving the car, hospital treatment, and clinical consultations. This gave us an opportunity to observe and experience how hearing difficulties affected everyday life and social interactions outside the home. Two audiologists included in this study, one in Georgia and the other in the UK, also gave us the opportunity to make observations and to engage in informal conversations in their clinics. Another important aim of the study was the production of ethnographic documentaries for educating audiologists at seminars organized by the Ida Institute (See https://idainstitute.com/what_we_do). Filming therefore became part of the project, and the rushes are part of the empirical material.

The two local audiologists with private practices helped us recruit and make appointments with participants among their patients (US) and clients (UK), as well as the latter’s relatives (partners, spouses, parents, and children). The participants were informed verbally and in writing about the study, initially by the audiologist, who also scheduled some of our appointments. Later on, at our first meeting with the participants, we also informed them about the study and gave them an opportunity to comment on it and ask questions. All the participants signed an informed consent form and a release form, and they have all been anonymized. (Authors’ note: There are, of course, cultural and political differences between the United States and the UK, as well as within both countries, notably in the differing organization of healthcare services and health insurances. These differences do not have a significant impact on our analysis and findings. Instead of referring to the specific countries, therefore, we use the term “Euro-American.”)

The majority of the hearing-impaired participants could not determine the cause and onset of their hearing loss. All of them had suffered from hearing loss for a number of years, and for most of them it was progressive. Some believed it had been caused by working with noisy equipment, while others cited ear infections or mumps. Other informants stated that hearing problems ran in their family, since their parents or siblings were also hard of hearing. For others, their hearing loss remained a mystery.

Those with late-acquired hearing loss reported that they were initially unwilling to admit the problem, and that they went through a long period of disbelief and denial, trying to downplay or even hide the problem (similar to observations in the research by Hallberg11,12). Gradually, however, they had to acknowledge that the relational problems they were encountering were linked to their hearing difficulties and not, as some of them thought, to other people mumbling. Eventually, they recognized that they were suffering from hearing loss because difficulties in understanding what was said were noticed in different social situations: in the home, in daily interaction with close partners or family members, in social gatherings, or at work (see Bisgaard8).

Hearing something but not understanding it was a common experience among the participants. They were able to communicate in face-to-face situations and quiet environments both with their partners and with us.

Interviewing. The interviews were prepared, conducted, tape-recorded and analysed by the first author. The second author filmed a major part of the interviews to be used for documentaries. The interviews lasted from 1 to 3 hours. With regard to the filming, it was explained to the participants that the cameraman was not to be considered a “fly on the wall” or unobtrusive observer, but more like “a fly in the soup.” Thus, we had no intention of hiding the presence of the camera or instructing the participants in how to react to it; if they wanted to look at the camera, comment on it, or say something to the photographer (second author) while filming, they could do that. As is customary in most documentary filmmaking, however, people tended to forget about the presence of the camera after a very short time and concentrated on the conversation with the interviewer.

The interview strategy was open-ended. First, the participants were invited to tell their story of their hearing loss in order to bring their own experiences and concerns to the fore. The interviewer then focused on how the hearing loss had affected their everyday lives and their relationships with their spouses and other family members. Their partners were asked the same questions. (Authors’ note: Hallam et al4 assume that the interviewer’s first-hand knowledge of hearing loss [as hearing-impaired] “enhanced his credibility, facilitated empathy and eased the exploration” [p273]. However, the authors do not explain why this was the case, nor do they reflect further on this position. Although we did not have such first-hand experiences of hearing loss, we do not believe that this constituted a disadvantage or represented an obstacle to our data collection or our analysis.)

The participants were interviewed several times in different social configurations, either alone or together with partners or family members (see Tables 1 and 2). Interviewing most of the participants more than once made it possible for the interviewer to listen to the interviews and evaluate whether it was beneficial to probe some issues more deeply. It also gave the participants the opportunity to reflect on what they had said and expand on their statements the next time we met them. Interviewing the partners separately and together, and sometimes with parents or adult children, provided information about their different experiences and perspectives on the impact of hearing loss.

All the participants wore their hearing aids on a regular basis. However, they also relied on their lip-reading skills to be able to follow a conversation. Being able to see the speaker was, therefore, crucial for their hearing and understanding. During the interviews, the participants were able to communicate in face-to-face situations and in quiet environments, both with their partners and with us (the exception being a little girl with a cochlear implant). Generally, no problems arose in carrying out the interviews. Our Danish accents and choice of words sometimes made it difficult for the hearing-impaired to understand what we were trying to say.

Talking about hearing. Even though our study focused on hearing loss, we tried to be attentive to other life concerns or conditions that may interact with or even be more significant than participants’ hearing problem (cf, Hallberg and Barrenäs11). For example, one hearing partner felt it important to emphasize that his wife’s hearing loss was not a big problem anymore. They had become used to coping with it on a daily basis and had a good life. Other health problems, however, such as his heart condition, caused them growing concern. One participant who had recently fallen ill with severe kidney problems and was on dialysis several times a week remarked that “hearing has become a minor part in (their) life,” even though his hearing loss was causing him problems in his frequent encounters with the healthcare system. One such problem was that the nurses wore masks over their mouths, so he was unable to lip-read. Because hearing loss is most common among elderly people, it often goes hand in hand with other age-related health problems and sensory losses,17,24 and therefore cannot be isolated from other life concerns.

The majority of the participants in this study have had their hearing loss for many years, and they were trying to cope with it, without necessarily being verbally explicit about how they dealt with it or by putting it on the agenda in their everyday life. Nevertheless, initiating a conversation about hearing loss appeared to be a positive experience for the participants. In the process of describing to us how they experienced and handled their hearing loss in different situations, the participants seemed to become more aware of their different strategies for coping, as illustrated in the following excerpts:

After talking to you yesterday, I thought a lot about this. It made me think about things that I had not realized before, and about the way we communicate, and the things that you just tend to take for granted. So it has been interesting, really. [The interviewer asks her to elaborate on this]. Because I needed to explain things to you, and I suppose that made it clearer in my own mind, why I could not understand my husband [her spouse]. He is the most important person, and I need to understand what he is saying. And I kept thinking that it is my failure. So, when I began talking to you, I began to realize all the elements making it possible or impossible. —Gina

In pursuing the objectives of the project, we enabled participants to talk about and reflect on their hearing loss in new ways.

Analyzing hearing loss. After fieldwork, the first author produced written transcripts of the interviews and rushes and reviewed the tape-recorded interviews, rushes and field notes. The first author also carried out the analysis and writing of the present article. Recurrent topics (phrases, issues, statements) were identified, compared, and categorized. For example, several participants talked about the interactional implications of asking for repeats and of losing spontaneity. These cases were grouped in a more abstract category, such as “temporality in social interaction.” In this stage of analysis, the findings were also related to theories of social relationships, conversation, and sociability in order to understand and conceptualize them in new ways.

RESULTS

Conjugal Frictions

Sometimes, you know, [my wife] used to shout to make me hear, but I always thought she was shouting because I was annoying. —Luke

I do get frustrated because I know I can’t talk to her in another room. […] And even if she is facing me, she can’t hear me because she can’t see me to lip read at a distance. —Mary’s husband

This section explores the effects of hearing loss on conjugal relationships. where the partners interact on a daily basis by living, eating and sleeping together. We examine how both the hearing-impaired person and his or her hearing partner became aware of, and experienced the hearing loss, and how it has affected their relationship.

While the hearing-impaired participants frequently mentioned a particular embarrassing situation that led them to consult an ENT specialist or an audiologist, it was most often the close partner who insisted on the consultation. The hearing partners recalled increasing communication difficulties, the high volume of the television, and their partner’s withdrawal from conversations (keeping quiet or sitting alone) as the first indications that there was a hearing problem. Recognition of a partner’s communication problems is well illustrated by the following quote:

My experience mirrors Gina [the wife] in that I gradually became aware that there was something that she did not understand, and I had to be careful about how I said things and make certain that I was looking at her. Otherwise she was not going to get it… It is a process that continues. It is getting worse. We are learning and adjusting as we go along. —Gina’s husband

Embarrassment and frustration were the terms used most frequently when participants described how the hearing loss affected their relationship. As we will demonstrate below, these feelings are linked first to the experience of not being heard or listened to, and secondly, to the timing and tempo of everyday conversation and interaction.

Listening and Hearing

One thing with people who are partially deaf: you don’t actually hear things. You have to listen…You have to concentrate on hearing all the time, you have to listen. And normal people don’t listen, they just hear, it is automatic. And that what I was beginning to say to Luke: ‘You have to listen, because you are getting a bit deaf, and this was when he was in denial. —Luke’s wife

Initially, the hearing partner felt frustrated because the hearing-impaired partner did not seem to listen. Listening, which is supposed to be intentional and selective, is often contrasted with hearing, which is supposed to be an indiscriminate and automatic receiving of sound.25 As one participant (Frederic) told his wife, who was deeply frustrated because he was not listening to her: “I am listening, but I can’t hear,” meaning that he was not intentionally ignoring her or her wish to share something with him. Others reported that they could “hear, but not understand,” meaning that, even if they listened intently and heard something, they could not make sense of what they received. Another source of frustration could be the hearing-impaired spouse lacking the will to act on their problem. This ultimately caused one hearing spouse to make an audiology appointment without her husband’s knowledge.

Another source of frustration arose if the hearing-impaired partner forgot to put on the hearing aids, or simply switched them off. All participants took out their hearing aids occasionally and went “off-line,” either because they wanted to give the ear canal a rest from the device physically, or because they wanted to enjoy the relative silence of the hearing loss for a while.

However, switching off the hearing aids or forgetting to put them on may also signal an unwillingness to listen and engage socially. One 70-year-old participant had had a cochlear implant one year before we met him. His new hearing was “a miracle,” he said, because he was able to hear sounds that he had not heard for “almost a lifetime” (eg, birds, squirrels, water running, and the coffee machine). The implant had also enabled him to socialize with his family and friends again. Nonetheless, according to his wife, he often forgot to put his hearings aids on in the morning. His wife worried when he did not answer her, now that he could hear, and she felt frustrated and upset about his forgetfulness:

This is our biggest fight. How can you forget something that helps you hear? I can’t see without my contacts, so I put them on the first thing in the morning. So why doesn’t he put on his hearing aids? —Frederic’s wife

Another couple agreed that they did not consider the husband’s hearing loss a problem. They “dealt with it” and emphasized that it was “not a big issue” in everyday life— with one exception, however: the wife felt terribly frustrated that her husband often turned his hearing aids off when he came home from work, thereby making it impossible for them to have a routine conversation. The husband explained why he switched off his hearing aids:

It is getting progressively noisy, so it is wonderful to switch them off …It is something of a paradox, isn’t it? You suffer from hearing loss, and then you become acutely aware of noise.

The cases reported above illustrate that managing noise by forgetting or switching off one’s hearing aids is a source of anxiety or frustration for the hearing partner. In situations of intimate communication, hearing partners cannot be sure whether their hearing-impaired partners really cannot hear them, whether they do not “listen,” or whether they simply do not want to hear them. Being “unable to hear” is simply a disability and therefore excusable; however, not listening or not wanting to hear is an intentional act, and is viewed as anti-social, unacceptable, and distressing.9 In the quote introducing this section, Luke’s wife states that people with hearing loss have to listen. Another participant noticed that she actually liked to listen, and she was convinced that her hearing loss had made her a good listener:

One thing that the hearing loss did— that I developed that I may not have developed as a normal-hearing person—is that I am a very careful listener. I like to listen, so I prefer to listen more than talk when I am around people. —Anna

Losing Spontaneity

In general, the hearing-impaired participants felt embarrassed when asking other people to repeat themselves. This is in part because they associated the request to repeat with being slow-witted and because it tends to disturb the flow and progression of normal conversation and social interaction,23 thus making the situation more complicated and uncomfortable. Feelings of embarrassment became more acute in social situations outside the home, as we shall see later. Nevertheless, frequent requests for repetition also caused friction within the context of close relationships and everyday one-to-one interaction. This general finding is well illustrated by the following quotes from two hearing partners:

I noticed that you [addressing his wife] do think sometimes that I sound aggressive towards you, but it is not intentional. It is because you did not hear me the first time. Perhaps it is a bit of frustration. I do speak louder, and you then get a bit upset because of my speaking louder, and I sound aggressive. But I am not actually trying to sound aggressive; I am trying to make myself heard. [addressing the interviewer:] We do find the situation sometimes… after she has said ‘pardon’ three times, I get frustrated. I know that it is a problem, and it has been a problem for years… If I can’t be heard, there is no point for me in saying it. —Mary’s husband

It is a sad fact that often I will need to repeat things two or three times to Gina before she gets it. What happens is that you try, as you are repeating it, to improve the clarity of what you are saying, and by the time you get to the third time, that is when she is taking it on board. It has become so precise, pedantic and exact in what you are trying to say that it sounds— and let us be honest— probably does contain some elements of irritation. [Gina, nodding affirmatively, adds “Yes.”] So by the time she is getting it, I am irritated, which I was not when I started, and I am not as soon as I have said it. But the only bits she gets is a sense of irritation, which is partly justified and partly because I am being very precise and pedantic about the way I am saying it…That is something we have to learn and that we both have to learn. —Gina’s husband

The hearing partners often admitted that they became irritated when having to repeat themselves. In the process of repeating, the tone of voice shifts, making the speaker appears more and more agitated or even aggressive. Moreover, in the same process, the content and linguistic richness of the initial message are reduced to what is absolute necessary. Asking someone to repeat something, however, and insisting on being heard could also take on an aggressive tone. For example, one hearing person found that his partner often acted aggressively towards other people when he asked them to repeat something several times.

The feeling of having to censor or filter out what one says, and the concomitant loss of spontaneity were significant themes in the hearing partners’ accounts of their spouse’s hearing loss.3,4,6 Both themes are pointed out in the following quote:

It is the lack of spontaneity and the continual thought that it is necessary to filter and censor everything that you are saying and the way you are saying it to avoid some of the problems that Gina otherwise has. Is it worth saying and potentially saying three times or else is it much better not even to start? —Gina’s husband

What you lose is a lot of spontaneity. It is totally pointless me making an off-the-wall remark, a new subject, a comment, a joke, because firstly the situation physically has to be right, in that we have to be looking at each other, which is obviously not the case a lot of the time…The adjustments come in asking yourself the question. If I say this, is it going to be heard? If it is not going to be heard, is it worth going through a process of engaging attention to make the remark. So a lot of the time you— no— and you just don’t. —Gina’s husband

In general, making oneself heard is hard work for the hearing partner. It is therefore tempting to not make the effort and to give up sharing small talk, whims, ideas and jokes with the hearing-impaired partner.3 In particular, several participants bemoaned the loss of joking in everyday life. As one hearing partner observed, “If someone makes a joke, it is difficult for Nicklaus to pick it up, and it is also difficult to then repeat that, because any joke at the table in repeating is not funny” [Nicklaus’s partner].

The same person felt that the hearing loss had led to “a more measured quality of how you deal with life,” in the sense that he had to be constantly “on guard” when interacting and communicating with his partner. To the hearing-impaired, this measured manner, reticence, and selectivity in conversation could be quite distressful. As Gina said, “The worst thing is when I ask for repetition, and my husband says, “Oh well, this is nothing.”

This suggests that successful conjugal adjustments to hearing loss depend on how both partners manage to integrate and adjust to the hearing loss in their social interactions and the everyday lives of their relationship. As a young woman pointed out when considering how her hearing loss affected her relationship with her fiancé:

It is part of our relationship. We make sure that we hear what the other person is saying…we acknowledge we hear each other, and that I heard him even if I am not responding… we make sure that we see each other as much as possible when we are talking. —Anna

As shown, hearing loss poses a challenge for maintaining spontaneous exchange and sharing of intimacy with close partners. Hearing loss disturbs the temporality of conversational exchange and thus undermines the confidence, intimacy, sharing and playfulness that lie at the core of conjugal relatedness in Euro-American societies.26 The consequences for the relationship depend on the ways in which the partners manage to adjust to these challenges. Quite obviously, as one partner noticed, this is an ongoing learning process. Although the hearing partners in this study had gradually learned the necessity of speaking clearly and slowly, being patient and ensuring physical, face-to-face proximity when talking to their hearing-impaired partner (eg, getting the partner’s attention before speaking to him or her), they also occasionally forgot to do so. However, there are indications that counselling in the private home may support this learning process and reduce the conjugal friction caused by the hearing loss.

Only one couple had had counselling in the home (Mary and her husband). This “on site” counselling was highly appreciated by both partners because they learned how, in small ways, they could facilitate their conversational exchange and their interaction in the particular soundscape of the home, thereby trying to reduce frictions and frustrations.

Mediating Partners

It could be a painful and sad experience to witness the hearing-impaired partners’ increasing communicational difficulties in social situations:

For me personally, it was a difficult experience watching Nicklaus declining. Not declining physically, but declining [in] spirit… It did not affect our relationships because we could still talk on a one-to-one basis. —Nicklaus’s partner

Hence, hearing partners often took on the responsibility for facilitating social intercourse and tried to prevent the impaired partner from becoming excluded from social interaction or making a fool of her- or himself.4 In this way, hearing partners also helped mediate the impression their partner made in social situations.20

Morgan-Jones4 notes that the hearing partner often takes on roles such as “buffer, interpreter, mediator, prompter, advocate, monitor and editor.”3 This role-taking is also in line with Hallberg and Barrenäs’s concept of mediating strategies.11 Mediating strategies cover:

- Controlling the situation by listening both for oneself and the hearing-impaired partner in order to involve the hearing-impaired partner in the conversation or social interaction;

- Navigating the hearing-impaired partner away from potential stressful situations; and

- Privately advising the hearing-impaired partner.11

The hearing partners in our study used all three strategies (which were sometimes also used by other relatives and good friends). However, our findings indicate that mediating strategies were neither fool proof nor fixed plans; their successful use depended on situation and context.

The hearing partners tried to smooth away difficulties and facilitate social intercourse and sociability by informing their hearing-impaired partners about the content of the ongoing conversation, repeating what was said or providing clues to the topic of the conversation: “It helps a lot if you know what the subject is. Then you fill in,” as Gina, a hearing-impaired woman, said of her husband’s support.

At times the hearing partner would also warn visitors or strangers of their partner’s hearing difficulty and offer them advice on how to deal with it. Close partners also tried to ensure that their hearing-impaired partners did not break the social rules of conversation: A hearing-impaired woman explained: “My husband has to keep an eye out to make sure I am not ignoring somebody.” The hearing partner’s role as translator and mediator11 therefore demands a great amount of social attentiveness. They are both “on call,” but also “on guard”:

When we are in company with other people, I am always conscious of the fact that Gina may be excluded. So I am continually having to assess: Is she happy being excluded? [Gina : interrupts and laughs: “Sometimes I am”]…or is it something where she would like to be included. —Gina’s husband

In general, these mediating and supportive acts were highly appreciated by the hearing-impaired partner; especially if they were discreet. They were seen as signs of love and support. However, the hearing-impaired participants also often said they had a guilty conscience about being dependent on their partner, fearing that they were a burden on their partner at social gatherings. Thus, love, responsibility, and dependency intersected when close partners joined social gatherings.

The partner’s mediating efforts did not always go smoothly, however. There could be moments of conflict and embarrassment, as illustrated in the following exchange between a husband and his hearing-impaired wife during an interview:

Mary’s husband: If we are in mainly social situations, because I would not bother when we are at home, if we are in a social situation where she raises her voice and talks too loud, I cut it down a bit [gesturing with his hands] and she gets really angry, and yet she does not realize that speaking so loudly is bringing attention to herself… I think one [example] was recently at a dinner, when we were out to dinner and her voice was far too loud in that situation. She does not realize, so I tone it down a bit. Oh, dear! And that is the wrong thing to do; she hates it.

Mary: It is pride, is it not?

Husband: Yes, but I can’t accept it when we are out with friends, and she is shouting. And you know [glancing at her], it can be very difficult.

Mary: Yes, I am sure.

Husband: All our friends know exactly what I am doing because it is obvious, but it does upset her.

Mary: Yes, again, but it is drawing attention to me, and that is what I find upsetting.

Mary: Yes, but you are bringing more attention to yourself when you are shouting.

Husband: Yes, I take your point.

This discussion is but one example of how the hearing partner may feel embarrassed by the way the hearing-impaired partner manages the hearing loss in social gatherings. In the above case, the husband felt uncomfortable about his wife’s vociferous impression and tried to “save her face” and avoid social discomfort by signalling to her.

Several of the hearing-impaired participants were unable to gauge how loud they spoke. In most social situations and speech events in a Euro-American context, speaking too loud violates the cultural rules for conversations, indicating that the person may be ill-mannered, intoxicated, aggressive, mentally disturbed or lacking self-control.

In his discussion of the ways in which sound has served historically to locate and identify place, class, and national identity, Mark M. Smith writes that “nobles generally counterpoised themselves against the masses by embracing quietude, not loudness.”27 They could afford noise-muting furniture, and this “ability to afford and insist on quietude became increasingly associated with class and notions of refinement and taste.” This association between nobility and quietude may partly explain the social discomfort that arises when people speak loudly. In trying to join in and be sociable, hearing-impaired persons run the risk of appear to be brash because they are not always aware of how loud their own voices are. Speaking too loudly is an example of an “unmeant gesture”28 that discredits the person’s self-presentation (in this case, that of Mary), leading to both individual embarrassment and social discomfort.

Speaking too loudly may be one unintended side effect of hearing loss; another is unclear speech. A few of the participants had problems in articulating certain words. Unclear speech is also culturally associated with being awkward and is yet another stigmatising feature that may accompany hearing loss.

It is not only the hearing-impaired person who may appear to be brash in embarrassing ways. This was observed by a hearing partner, as the following interview excerpt illustrates:

Husband: There is no problem when we are close together, you know. We can sit at dinner and talk together. No problem. But we do have a problem now when we are going out with friends. And it does have a bad effect on her [his wife] because she feels she is missing out so much…We are going out most Friday evenings with a group of 18 to 20 friends, and when you are sitting in a pub— a noisy pub—and you [addressing his wife] are trying to talk and somebody who is not close to her wants to talk to her; then there is a problem. She just can’t hear them. And some of our friends get frustrated because they don’t live with her as I do.

Interviewer: How do they show their frustrations?

Husband: Sometimes they shout. But we have got some of our friends now, they overdo it. We’ve got one who speaks extremely loud to you [addressing his wife]. And I find this a bit embarrassing. I know she is doing it to try to be kind, but, you know, the way people who are not used to talking to a deaf person; it can be quite frustrating because it makes you look as you were not all there, as it were. You are not mentally retarded [laughter]…But it does… mean that, when we are out, most of her conversation, whether she likes it or not, has got to be with somebody who is very close to her.

This quote exemplifies hearing partners’ attentiveness to how the hearing loss affects their partners in social situations, and the embarrassing moments they may experience from the ways in which other people react to their partner’s hearing problems. In the latter case, the friend spoke too loud and hyper-articulated, thereby drawing an undesirable degree of attention to his wife’s hearing problem.

Participants also mentioned good friends who (like their hearing partners) undertook a mediating role in social situations as a hearing-impaired person explains:

I have a lovely group of friends. One or two especially who make a point of seeing me looking a bit blank or confused, saying: “Did you catch that?” without making a big issue of that.

Mediating conversations thus requires certain social skills. In the above case, the mediating work also had to be performed with both attentiveness and discretion in order not to attract attention to the hearing difficulty.

Mediating strategies were not always chosen or improvized, however. A mediating role could also be imposed on the hearing partner by others, such that the hearing partner suddenly became a translator or interpreter. Gina’s (hearing) husband explains:

Very often people will physically sort of re-position themselves, but I am sure that some of it is subconscious. They will put themselves alongside me and sort of push Gina off to the one side and start talking to me, rather than talking to her.

In some situations, the hearing partner deliberately chose not to take on a mediating role. The partner of one hearing-impaired informant (Nicklaus), who often visited doctors due to his kidney problems, had decided not to accompany his partner to certain consultations. The partner had realized that, if he were present, the doctor or health professional would speak to and through him, and sideline the partner (who, as the patient, seemed to be the most obvious interlocutor). Apparently, if the hearing partner were present, the doctor would not make an effort to be heard, since speaking to the hearing partner was easier and more comfortable.

To summarize, the hearing partners took on the responsibility for involving their partners in social gatherings and for smoothing social interactions in order to avoid embarrassing situations. Mediating strategies, however, are not fixed action plans; their enactment depends on the situation and context, and mediation requires a considerable amount of social attentiveness, improvisation, and interpersonal skills. The demands of mediating sometimes made it difficult for the hearing partners to relax in social situations and to give in to sociability. The hearing partners’ mediating efforts were, in general, considered supportive and caring by the hearing-impaired partner—especially if they were performed with discretion. The same efforts, however, could also lead to the unintended exclusion and sidelining of the person with the hearing loss, in addition to that person receiving unwanted attention.

Troubling Noises

In general, the cultural values of hearing and the social implications of hearing loss are related to the particularities of the social situation and the soundscape (see Gell18). This means that what people hear (the auditory) is informed and framed by the social and acoustic environments.29

The research participants were often confronted with a widespread popular belief that people who suffer from hearing loss only need more volume, and/or that their hearing aids restore normal hearing. “Speak slowly, not louder,” as our oldest participant recommended, echoing the views of several of the participants. It was not always a question of volume (or exaggerated articulation), but of speaking slowly, clearly, and face-to-face. Indeed, it was a common experience among participants that people in general do not know how to communicate with a hearing-impaired person. Furthermore, there seems to be little awareness that hearing problems (eg, hearing pathologies) are complex and often require ongoing, corresponding technological and social adjustments. As one participant said, “The problem we [the participant and the audiologist] are working on is that I receive noise, but it is very difficult to pick out the words.” The technological and noise-managing aids were both individual aids but social facilitators, as well: they allowed her husband’s low voice to be more audible, and he was the person she most needed to hear in her everyday life.

The ways in which hearing loss affects close relationships are also actualized and negotiated in the context of particular soundscapes and social-sonic environments. The hearing-impaired participants were all troubled by loud sounds or background noise. In noisy environments, it was the effort to select the relevant words and meanings that caused problems. As a consequence, both the hearing-impaired people and their hearing partners had become more attentive to exposure to noise in everyday life. Our study shows that being together and interacting as a couple outside the home (shopping together or going for a car or a train ride while chatting about what you observe as you move around) becomes more complicated, sometimes even impossible, and that the extraneous noise adds to the difficulties of sharing small everyday happenings while they occur. A loud soundscape affected the couple’s reciprocal interaction and their social interaction with others. Successful noise management, like playing bridge, was a “couple’s project.” Both partners were necessary in order to manage noise with success.

Soundscapes in Western societies have changed radically in the course of the 20th century due to the artificial amplification of sound and man-made mechanical sounds stemming from cars, sirens, loudspeakers, microphones, aeroplanes, industrial machinery and modern warfare.30 In these increasingly noisy soundscapes, the ear has “to do duty as bodyguard, herald, explorer, and confidant,” as Hillel Schwartz writes.25 These “duties” are a particular challenge to the impaired ear, which receives a myriad of sounds but has continuously to struggle to make sense of them. Managing noise is essentially a practice of navigating these increasingly demanding soundscapes.

We also observed that, when we joined the hearing-impaired research participants at meals, it was often quite difficult to integrate them fully into the conversation with the normal-hearing participants. We became acutely aware of these pressures when accompanying our hearing-impaired informant Gina to the market. Chatting while driving in the car or walking in the town was simply not possible because of the noise from the rush-hour traffic and from the street fair being held that day. The noise, which persons with normal hearing take for granted and can easily filter out, affected our interaction in a profound way. Later, we had lunch with Gina and her husband in a pub. The shopping had been a tiring experience for her, and in the pub, she had a particularly hard time hearing what we said because of the noise level. Changing the setting on her hearing aids did not seem to help her much. Gradually, she gave up and withdrew from our conversation. Suddenly an ambulance passed by on the road outside. The three of us hardly noticed it, or at least we could instantly categorize the siren as an irrelevant noise in that particular situation, but Gina lifted her hands to cover her ears: “Uh, that hurt,” she exclaimed. One of the participants suffered from tinnitus and feared exposure to noise. She always wore earplugs when she went out, and wore a headset when she fed the chickens and roosters on her farm or went to the cinema. Fear of noise made her avoid situations that she anticipated would be too noisy for her.

Similarly, another participant stated that, “Sometimes you hear too much.” He praised his new hearing aids but switched them off in social situations where there were a lot of people and a high noise level: “It [the sound] makes me nervous, and it hurts,” he told us. Switching off hearing aids to avoid noise was common among the participants. This noise awareness was also mentioned by several hearing partners. As a hearing partner (Gina’s husband) said:

I have become attentive to sound pollution. What I have become aware of is that I cannot have a conversation with Gina on a train or in a public place, because one is continually being bombarded with announcements, noise, and background music that totally preclude conversation. That is something that I have become much more sensitive about.

Hearing partners also worried about their partner’s safety in public places and in traffic, because they would not be able to hear approaching vehicles, sirens, fire alarms, smoke detectors, or loudspeakers. Safety concerns were also mentioned in relation to private domains and possible threats from outside:

What worries me most about Ellen, should I die and leave her here alone. She cannot stay alone because she cannot hear when she is asleep. I had the repairman come for the alarm system to service it. And she was asleep in her chair. And he rang the doorbell, and I let him in, and she was sleeping right on…so he served and fixed it and he was going to check. And he set the alarm off and it did not wake her. —Ellen’s husband

Beside the fear that Ellen would not hear the intruder alarm, her husband was concerned about her future life without him. His heart condition had convinced him that Ellen would outlive him, and he worried about her being on her own without him to “hear for her.” Ellen did not like to talk about that and glossed over the topic. In the course of the interview, however, it emerged that she was also worried about not being able to hear her husband should he need assistance or cry for help.

We have seen that hearing loss alters social interaction in modern, urban soundscapes by inhibiting the intimate and confident conversational space (see Bull31); it hinders “walk and talk” and the sharing of observations and thoughts outside the relative quietude of home. Hearing loss makes it more difficult to navigate soundscapes, and it causes safety concerns since the hearing-impaired ear poses barriers to playing the role of “confidant” and “bodyguard.” The huge challenge for the hearing-impaired is not just to manage noise, but to manage noise in socially appropriate ways. Managing noise is thus not just a technical problem to be solved solely by technological means: it must also be solved socially. Dealing with hearing impairment requires both technical and social solutions.

One participant felt it was a “bit of a cheat” when his hearing-impaired partner had his hearing aids fitted, “Because if you go into the room [the consultation room at the clinic] there are carpets on the floor, there is wood on the wall and there is no sound from the air-conditioner.” He had observed that the hearing aids seemed to work well in the clinic, but as he also stated:

The minute he [Nicklaus] walks out the door into the street with the cars and the people and the pollution, he cannot hear a thing. So I would like to say to the audiologist, “You fitted it up, you have done the setting. Now, walk around the block to see if it works fine.” —Nicklaus’s partner

Even though the audiologist played different forms of background noise as part of fitting the hearing aid, both partners emphasized that it was not the same as in “real life.” The study thus indicates that audiologists and hearing care professionals could benefit from meeting their clients outside the clinic.

Conclusion

Hearing loss is one of the most common disabilities, with a large number of people having to deal with it in their everyday lives. This study suggests that anthropological methods combining in-depth interviewing with participant-observation in different contexts (eg, joining people where they live, sharing time with them, and taking part in and observing their activities) can produce a more nuanced understanding of the social implications of hearing loss and how social factors affect individual experiences and practices.

Hearing loss puts pressure on social relationships by complicating the conversational exchange that is so crucial for forming social relationships. These interactional complications, we suggest, are closely related to the ways in which hearing loss disturbs temporality in social interaction. Both the hearing-impaired participants and their close partners bemoaned the loss of spontaneity and the difficulties of sharing small unexpected incidents, observations and small talk in their everyday interactions. This loss of everyday spontaneity, and of sharing experiences, influenced conjugal relationships because sharing is a basic element in conjugal relatedness.

Although people who are hard of hearing may succeed in hiding their hearing difficulties and put off seeking help, our findings indicate that their close partners will gradually notice problems in their daily communications and interactions. It is often the hearing partner’s frustrations or an embarrassing social event that persuades the hearing-impaired person to acknowledge and act on the problem. Hearing loss, therefore, is a social and relational challenge: it both affects and is affected by social relationships. As Knussen et al14 point out, the way hearing loss affects social relationships and the forms of social interaction on which these relationships are based, are shaped by the quality and nature of these particular existing relationships.

Hearing loss should therefore not be considered an individual problem: it is always shared and shaped by the sonic environment and social context.

As we have demonstrated, hearing partners (or very good friends) took on the responsibility for integrating their partners in social interactions by facilitating their participation and preventing embarrassing situations. As social mediators, they had to be socially attentive and good at improvising. Mediating strategies also had to be performed with discretion in order not to draw too much attention to their partner’s hearing difficulty. However, hearing partners did not always succeed in this. As we ourselves experienced, normal hearers may forget about (or ignore) the hearing loss and revert to easier means of communication concentrating their attention on the hearing partner. As a result, the hearing-impaired person may feel sidelined and excluded.

The partners experience and handle the effects of the hearing loss differently and from different positions. Both the gender and age of the hearing-impaired person seem to play a role in the way the hearing loss affected the relationship, but how gender makes a difference in relation to hearing loss needs to explored further.11

Practical solutions and treatment should take account of the social context. This could be done by new kinds of treatment protocols or a more detailed examination and survey of the hearing-impaired person’s daily life and social contacts.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Ida Institute. The authors would like to thank the participants in the study for sharing their experiences with us. We would also like to thank the audiologists Robin Hardin, Mary Youngman, Janine Appleby and their staff for their great support. Finally, we thank the Ida Institute staff for their hospitality and encouragement.

References

-

Davis A. Hearing in Adults. London: Whurr Publishers, Ltd:1995.

-

Robertson M. Counselling clients with acquired hearing impairment: towards improved understanding and communication. Int J Advancement Counselling. 1999;21:31-42.

-

Morgan-Jones RA. Hearing Differently: The Impact of Hearing Impairment on Family Life. London and Philadelphia: Whurr Publishers;2001.

-

Hallam R, Ashton P, Sherbourne K, Gailey L. Persons with acquired profound hearing loss (APHL): How do they and their families adapt to the challenge? Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine. 2008;12:369-388.

-

Hétu R. Jones L, Getty L. The impact of acquired hearing loss on intimate relationships: implications for rehabilitation. Audiology. 1993;32:363-81.

-

Scarini N, Worrall L, Hickson L. The effect of hearing impairment in older people on the spouse. Int Audiol. 2008;47:141-151.

-

Yorgason JB, Piercy FP, Piercy SK. Acquired hearing impairment in older couple relstionships: an exploration of couple resilience process. J Aging Studies. 2007;21:215-228.

-

Bisgaard S. Coping with emergent hearing loss: expectations and experiences of adult, new hearing aids users – an anthropological study in Denmark. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Copenhagen;2008.

-

Dahl MO. Twice Imprisoned: Loss of Hearing, Loss of Power in Federal Prisoners in British Columbia. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of British Columbia;1995.

-

Echalier M. Hidden crisis: why millions keep quiet about hearing loss. RNID: London;2009.

-

Hallberg LR-N, Barrenäs M-L. Living with a male with noise – induced hearing loss: experiences from the perspective of spouses. Brit J Audiology. 1993;27:255-261.

-

Hallberg LR-N. Hearing impairment, coping and consequences on family life. Journal of the Academy of Rehabilitative Audiology. 1999;32:45-59.

-

Hétu R. The stigma attached to hearing impairment. Scand Audiol. 1996;43:12-24.

-

Knussen CD, Tolson IR, Swan C, Stott DJ, Brogan CA, Sullivan F. The social and psychological impact of an older relative’s hearing difficulties. Psychol Health Med. 2004;9:3-15.

-

McKelling WH. Hearing impaired families: The social ecology of hearing loss. Social Sci Med. 1995;40:1469-1480.

-

Preminger J. Audiologic Rehabilitation with Adults and Significant Others: Is it Really Worth It? July 27, 2009. Available at: http://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/article_detail.asp?article_id=2246

-

Yorgason JB. Acquired hearing impairment in older couple relationships: an exploration of couple resilience processes. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute;2003.

-

Gell A. The language of the forest: landscape and phonological iconism in Umeda. In: The Art of Anthropology: Essays and Diagrams. London and New Brunswick, NJ: The Athlone Press;1999.

-

Kato K. Soundscape, Cultural Landscape and Connectivity. Sites: New Series. 2009;6:80-91.

-

Goffman E. Interaction Ritual. Harmondsworth: Penguin University Books;1972[1967].

-

Rapport N, Overing J. Social and Cultural Anthropology: The Key Concepts. London: Routledge;2000.

-

Moerman M. Talking Culture: Ethnography and Conversation Analysis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press;1988.

-

Clayman SE. The production of punctuality: Social interaction, temporal organization and social structure. Am J Sociol. 1989;95:659-691.

-

Heine C, Browning CJ. The communication and psychosocial perception of older adults with sensory loss: a qualitative study. Ageing and Society. 2004;34:113-130.

-

Schwartz H. The Indefensible Ear: A History. In: Bull M, Back L, eds, The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford:Berg;2003.

-

Gillis JR. A World of Their Own Making: Myth, Ritual and the Quest for Family Values. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press;1996.

-

Smith M. Sensing the Past: Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching in History. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press;2007.

-

Goffman E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin Books; 1990[1959].

-

Lundberg P. Blindhedens akustiske horisonter: om auditive kundskaber og en akustisk virkelighed. Tidsskriftet Antropologi. 2006/2007;54:21-44.

-

Connor S. Feel the noise: Excess, affect and the acoustic. In: Hoffman G, Hornung A, eds. Emotion in Postmodernism. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter;1997.

-

Bull M. Soundscapes of the car: A critical study of automobile habitation. In: Bull M, Back L, eds. The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg;2003.

About the authors: Tine Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, PhD, holds a doctorate degree in anthropology from the University of Copenhagen. She is professor of qualitative and ethnographic health research at the National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, and head of the research group Health, social relationships and structural conditions. Hans Henrik Philipsen, PhD, is chief anthropologist at the Ida Institute, in Nærum, Denmark. He applies his expertise as a social anthropologist by bringing insights from patients, their families, and health professionals to the innovation process to better understand the challenges and opportunities facing modern hearing care.

Image: © Dave Bredeson | Dreamstime.com

.gif)

Publishing this study is priceless! I will be showing this to my hearing impaired husband who refuses to wear his hearing aid. I am soft spoken and a little shy and have been berated for not talking loud enough, and even been told by him that I have a speech impediment! As a hearing person you just don’t realize how the background noises can affect these interactions! He is not a patient person and it has gotten to the point that he stops trying to hear me, he will keep walking into another room when I talk, putting the onus on me to talk louder and chase after him. It’s not helping my self esteem and it’s eroding our marriage. When we visit with friends he interacts well with them and I feel ignored, but this article has alerted me to the fact that he makes an effort with them and maintains face to face conversation and there’s very little background noise, so there’s nothing to interfere like cooking noise or a loud TV during visits with friends. When he misunderstands someone during a visit, it’s because the environment suddenly became noisy or the face to face contact had been broken because he’s doing something like bending over to tie his shoes.

So thank you, this article really showed how the onus is on both people and helped me put all the pieces together!

I have this problem

i hear loss

i am very embaressin all the tim in the work and in social relationship.

je maitrise bien le français que l’anglais.

j’ai lu cet article et il correspond bien à ce que je vis .

Merci pour cette publication.

pour faire face à ce problème , l’apport de l’appareil d’audition est il la bonne solution.

Merci beaucoup

Puts alot of strain on the marriage.

Good Afternoon – I just happened upon this study whilst seeking a solution to ‘echoing hearing loop’ issues.

I found your research article absolutely fascinating and could relate to far too much of the detail! I certainly can relate to many of the situations that you have explored. It is a very sad fact that poor hearing is still viewed by many as a source of humour and not something to be taken too seriously, especially if the sufferer has misheard and unwittingly responded unexpectedly or inappropriately. My wife and I joke on a personal level that there are times when we appear to be holding two entirely different ‘parallel’ conversations (usually as a result of intrusive external sound sources).

I gained some reassurance to read that what are everyday experiences for myself and my wife are not that unique. It can only be hoped that greater understanding of the problems will be enhanced by your article.

I have bookmarked your article and will no doubt read it again.

Kindest Regards

Bob (UK)