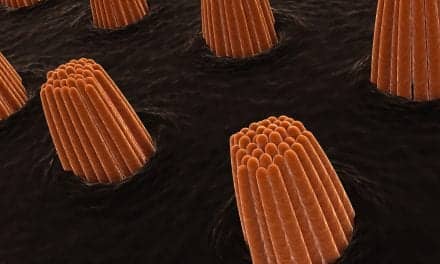

Recent research by a team at the Oregon Health & Science University, Portland shows that a key gene known as Atoh1 (also known as Math1) can not only cause cells to develop into hair cells but that these cells function like normal hair cells.

"Our work shows that it is possible to produce functional auditory hair cells in the mammalian cochlea," says John Brigande, assistant professor of otolaryngology at the Oregon Hearing Research Center in the OHSU School of Medicine.

Hair cells can be damaged and lost through aging, noise, genetic defects, and certain drugs and, because the cells don’t regenerate, the result is progressive—and irreversible—hearing loss. Damage to these cells can also lead to tinnitus.

Brigande and colleagues were able to produce hair cells by transferring Atoh1 into progenitor cells in the inner ear of developing mice. This type of cell becomes specialized to perform different functions during development, according to the instructions they receive from genes. The gene Atoh1 is known to turn progenitor cells into hair cells, but it was not previously known whether the hair cells would work normally if Atoh1 was introduced artificially.

To find out, the team inserted Atoh1 into progenitor cells along with a fluorescent protein molecule that is often used in research as a marker, to make cells easily visible. They were then able to see that the gene transfer technique resulted in mice being born with more hair cells in the cochlea than are normally found.

Anthony Ricci, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, demonstrated that the gene-treated hair cells function like ordinary hair cells.

[Source: Medical News Today]