Explaining the benefits of products and services is the key to future market growth

Evidence is presented that suggests price is not the primary barrier to hearing aid adoption. Findings from this study do, however, indicate that lack of hearing aid adoption is correlated with at least two factors: benefit deprived marketing and pricing strategies (bundling of product features and services).

The retail price of hearing aids, which averages about $2,000 per unit in the United States, continues to prevail as a primary barrier to the use of these devices by consumers. To lessen the impact of price as a barrier and substantially increase the number of hearing aids dispensed to non-users, it has been advocated that hearing aid cost be reduced.1-3

However, economic estimates do not support this idea. Specifically, devices fully or partially subsidized by the US federal government are expected to yield only small gains in adoption rate, based on the inelastic demand for this technology.4 In this paper, we contend that price is not a primary factor to the adoption process. Instead, we reason that impaired listeners are not adopting amplification, in part, because of the market’s lack of emphasis on the evidence-based potential benefits of this technology in a meaningful way.

Advertisements in local newspapers and online frequently illustrate this point. In many ads, discounted price values are often framed to attract potential users to a practice (eg, “Was $2,000, Now $1,000—Save 50%”), while the benefits offered by the technology are either vague or technical. The emphasis on price is not meaningful because it fails to capture the potential value perceived by the consumer. In other words, price is simply the amount a consumer pays for a product or service. In the event that price outweighs the perceived benefits of the product and service to a potential user, the perceived value will be low, increasing the likelihood that the hearing aid will not be adopted. However, when the benefits of the product and service are perceived as greater than their costs, the perceived value is high, and the likelihood of trial and adoption increases.

Figure 1. Advertisement with sparse details (Group 1).

Figure 2. Advertisement emphasizing technological benefits using industry terminology (Group 2).

Figure 3. Advertisement emphasizing potential user benefits (Group 3).

Hearing aid adoption rates have remained essentially unchanged over the past 30 years.4 A potential reason for this stagnant growth is our industry’s use of a pure or partial price bundling strategy (ie, the practice of offering a fixed combination of products, services, or both, into a single price). By definition, the advantage of price bundling is to provide the consumer with a single price for a product, service, or both, at a cost that is less than the total price for all items purchased separately. A disadvantage of price bundling—as it pertains to the hearing aid market—is that any perceived benefits from the technology (eg, improved ability to understand speech in the presence of competing noise, reduced listening effort, etc) are obscured.

In order to highlight the individual technology benefits of amplification, unbundled pricing (ie, individual pricing for each product and service or individual pricing for product and service packages) is recommended. Examples of the pure and partial bundled pricing strategies, and the unbundled pricing strategy, are illustrated in Table 1 for the hearing aid shown in Figure 2.

In this paper, we provide the reader with preliminary findings from an ongoing study that is being conducted at the University of North Texas. The aim of this study is to query the price that experienced and inexperienced hearing aid users are willing to pay for adopting amplification technology and services, based on the perceived benefit of the features presented in bundled and unbundled pricing strategies.

Study Method

Participants. The preliminary findings reported here are based on responses provided by three groups, each composed of 40 retired participants with annual household gross incomes of less than $42,000. Participants in each group exhibited a bilateral symmetrical mild to moderately severe hearing loss. Participants were recruited through the University of North Texas Speech and Hearing Center, and various assisted-living residences, service organizations, and elderly community and activity centers located in the metro Dallas/Fort Worth area. In each of the three groups, one-half of the participants reported at least 1 year of experience with hearing aids, and the other half reported no experience with amplification. The groups contained equal numbers of females and males.

Questionnaire. Each group of participants provided dollar amounts to a questionnaire for the same hearing aid and professional service. The difference between groups was the manner in which the technology and professional service were framed. Specifically:

- Group 1 participants viewed a high-resolution color photograph of a generic hearing aid and sparse details of the technology available within the device (Figure 1).

- Group 2 participants were shown the same device, but the details of the technology were provided using industry terminology (Figure 2).

- Group 3 also viewed the same device as their Group 1 and 2 counterparts, but the details of the technology were provided in the form of potential user benefits (Figure 3).

The participants in each group were informed that the average price of their device was $2,000 (ie, price anchor).

The dollar amounts provided by each participant were also obtained using a bundled and unbundled pricing approach. Bundled pricing consisted of the participant providing the maximum value they were willing to pay for the features and service related to the device they were shown.

Unbundled pricing, on the other hand, was determined by showing each respondent in each group the generic hearing aid (in Figures 1-3) minus any text. Specifically, we asked participants to provide the maximum base retail price for a standard device (ie, BTE casing, ear tip, microphone, amplifier, and receiver). Next, each participant was shown their respective group’s photograph and accompanying text (ie, Figure 1, 2, or 3), and asked to provide the maximum individual price for the potential benefits of a technological or service correlate:

- Automatically increases the volume of soft sounds and reduces the volume of loud/uncomfortable sounds (ie, wide dynamic range compression, or WDRC);

- Improved ability to hear a talker in background noise (ie, directionality);

- Reduced listening effort (ie, noise reduction);

- A 2-year warranty to cover the loss and repair of the device; and

- All professional services related to the fitting of the device.

The overall retail price for a device was determined by taking the sum of the individual dollar values of the five potential benefits.

During data collection, participants were seated at a table across from the experimenter in a quiet room. No more than three participants sat at the same table at any given time. In the event that participants were tested in a small group, each participant was separated from their neighbor by at least one seat. Each subject was asked to keep their written answers covered and to refrain from providing their responses verbally.

Table 1. Hypothetical example of the bundled and unbundled pricing strategies for the hearing aid depicted in Figure 2.

Results and Discussion

Bundled versus unbundled price strategy. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to determine whether the independent variables of group, hearing aid experience (ie, experienced, inexperienced), and gender (ie, female, male) had an effect on respondents’ willingness-to-pay when the retail price of a hearing aid was provided in a bundled and unbundled strategy. Recall that a price anchor of $2,000 was provided to all respondents.

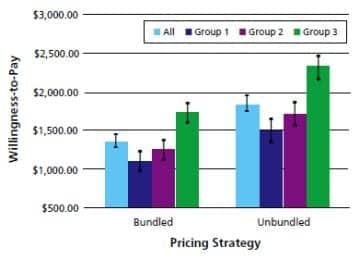

Overall, the mean retail price that respondents were willing to pay for the same device and professional services was $1,367.50 (95% confidence interval [CI95] ±$80.43) and $1,847.42 (CI95 ±$92.59) in the bundled and unbundled strategies, respectively. The difference between these means is statistically significant (p < .05), as indicated by the non-overlapping CI95 (Figure 4).

We believe differences in the willingness-to-pay by respondents based on pricing strategy can be attributed to the perception that the bundled pricing strategy masks value-based (ie, consumer needs and expectations) attributes—specifically, the five technological and service correlates detailed above. These attributes are all important to current and potential users.

We assessed this possibility statistically and found that willingness-to-pay in a bundled-vs-unbundled pricing strategy was influenced by the type of advertisement shown to a given group [F(4,216) = 12.72, p < .001]. As shown in Figure 4, the average retail price each group was willing to pay was significantly (p < .05) higher in the unbundled strategy for all three advertising frames. Note that the willingness-to-pay is not significantly different (ie, overlapping CI95) between Groups 1 and 2—who were shown Figures 1 and 2, respectively—in either the bundled or unbundled price strategy. Conversely, respondents in Group 3 were willing to pay significantly more ($583.13 more) for the same secondary attributes promoted in the unbundled strategy compared to the bundled strategy.

Figure 4. Willingness-to-pay results by group for the same hearing aid presented in a bundled and unbundled pricing strategy.

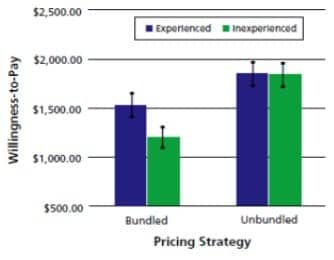

Figure 5. Willingness-to-pay results by hearing aid experience for the same hearing aid presented in a bundled and unbundled pricing format.

Results also revealed that willingness-to-pay in a given price strategy was statistically influenced by experience with amplification [F(2,107) = 10.46, p < .001]. Experienced hearing aid users were willing to pay the retail price of $1,530.83 (CI95 ±$113.76) for a hearing aid and professional fees presented in the bundled format, while listeners inexperienced with amplification were willing to pay $326.66 ($1,204.17, CI95 ±$113.76) less for the same product and service.

Conversely, both experienced and inexperienced listeners were willing to pay a similar price for a device and professional fees framed using an unbundled strategy (Figure 5). An additional analysis found a borderline significant effect between hearing aid experience and group [F(4,216) = 2.31, p = .06], with significant differences in willingness-to-pay stemming from higher monetary responses obtained from Group 3 in both pricing schemes. Collectively, these findings indicate that the bundling pricing strategy—where listener benefits are obscured (ie, Figures 1 and 2)—creates differences in retail price, especially between listeners differing in their experience with amplification.

This finding, although unexplored at this time, may be the catalyst for potential hearing aid wearers opting for lower-priced technology, including products available via the Internet. No significant differences (p > .05) were noted in willingness-to-pay for a device between genders.

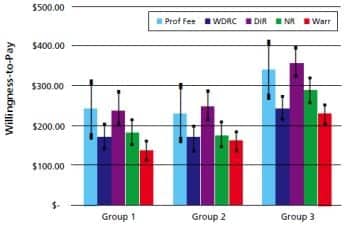

Figure 6. Willingness-to-pay results for hearing aid technology and professional service by group as determined in the unbundled pricing strategy. Key: Prof Fee = professional fee for services; WDRC = wide dynamic range compression; DIR = directional technology; NR = noise-reduction technology; Warr = service warranty related to device.

Willingness-to-pay for technology. A second MANOVA was undertaken to determine whether the same independent variables (ie, group, hearing aid experience, gender) influenced respondents’ willingness-to-pay in the unbundled pricing scheme for the potential benefits of five technological or service correlates previously discussed regarding the questionnaire (WDRC, directionality, noise reduction, 2-year warranty, and all professional services related to hearing aid fitting).

A statistically significant effect was found for the variable group [F(10, 210) = 4.02, p < .001]. Specifically, each potential benefit was found to be statistically significant (p < .05) between groups, except for professional services. As noted in Figure 6, mean willingness-to-pay values were similar between Groups 1 and 2 for each benefit (ie, overlapping CI95), while values reported by respondents in Group 3 were significantly higher (ie, non-overlapping CI95). This finding suggests that respondents are willing to pay more for hearing aid technology when perceived benefits (based on evidence-based findings) are provided in a meaningful manner.

With respect to hearing aid technology, experienced listeners, in general, were willing to pay significantly more than their inexperienced counterparts [F(5, 104) = 3.21, p < .01]. Here, only the benefits of improved ability to hear in background noise (ie, directionality) and professional services were statistically significant (p < .05) between experienced and inexperienced respondents. For directionality, listeners with hearing aid experience were willing to pay the retail price of $304.58 (CI95 + $31.78), while listeners inexperienced with amplification were willing to pay $258.33 (CI95 + $31.78). The analysis also revealed that listeners inexperienced with amplification were willing to pay $337.08 (CI95 + $60.09) for the dispenser’s time and expertise during the fitting process, while listeners experienced with amplification reported a significantly lower willingness-to-pay value ($203.67, CI95 + $60.09) for the same service.

Together, these findings suggest that price unbundling will yield at least two different niches, despite no significant differences in the total price: technology-based for experienced listeners and service-based for inexperienced listeners. No significant differences (p > .05) were noted in willingness-to-pay for a device between sexes.

Offering Evidence-Based Advertising and Unbundled Pricing

Price is not the primary barrier to hearing aid adoption. However, this study indicates that lack of hearing aid adoption is correlated with at least two factors: benefit-deprived marketing and pricing strategies.

To improve the adoption rate, hearing aid advertisements—both local and national—should provide potential users with evidence-based benefits of a given technology. In addition, the data suggest that an unbundled pricing strategy is favored by current and potential users over a bundled pricing strategy.

Clearly, more research is needed in this area, as well as research to determine whether unbundled prices should be centered on individual features and services or through packaged features and services. Whatever pricing strategy is used, it should reinforce the technological and professional service benefits portrayed in the advertising. Failure to show perceived benefit throughout the entire adoption process will result in the same low market penetration rates experienced during the past 30 years.

There are at least two different consumer niches in the hearing aid marketplace: technology-based for experienced listeners and service-based for inexperienced listeners. As a result, hearing care professionals are advised to tailor their information-based counseling during the hearing aid selection appointment to meet the needs of these two broad groups. For listeners inexperienced with amplification, it would be befitting to emphasize the value of personalized service, expert advice, and follow-up care over an extended period of time. A detailed review of the technological features and expected benefits in an updated hearing aid may be warranted for the experienced listener.

Lastly, we should be diligent not to barter quality for quantity. Specifically, we suspect that users will report lower satisfaction ratings for low-end hearing aids compared to high-end devices, because the former have been known not to meet the listening needs of the user.5,6 While providing a low-end product at a more affordable price might increase the hearing aid adoption rate, it could also increase the percentage of “in the drawer” hearing aids. Further, an unsuccessful experience with amplification could decrease the chance of users adopting more technologically advanced hearing aids—devices that can markedly improve their communication ability. Or worse, word of mouth will reinforce the mistaken perception that “hearing aids do not work.”

Acknowledgement

Funding for this study was provided by Unitron.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Amyn Amlani, PhD, at .

References

- Hearing Loss Association of America. Support HLAA’s Campaign to Make Hearing Aids Affordable. Available at: www.hearingloss.org/SpringAppeal_2011.asp. Accessed June 10, 2011.

- Donahue A, Dubno JR, Beck L. Accessible and affordable hearing health care for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2010;31(1):2-6.

- Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VII: Obstacles to adult non-user acquisition of hearing aids. Hear Jour. 2007;62(4):24-50.

- Amlani AM. Will federal subsidies increase the US hearing aid market penetration rate? Audiology Today. 2010;22(3):40-46.

- Callaway SL, Punch JL. An electroacoustic analysis of over-the-counter hearing aids. Am J Audiol. 2008;17(1):14-24.

- Ramachandran V, Stach BA, Becker E. Reducing hearing aid cost does not influence device acquisition for milder hearing loss, but eliminating it does. Hear Jour. 2011;64(5):10-18.

Citation for this article:

Amlani A, Taylor B, Tara W. Increasing Hearing Aid Adoption Rates Through Value-based Advertising and Price Unbundling. Hearing Review. 2011;18(13):10-17.