For at least three decades, several prominent audiology researchers have speculated that hearing loss can significantly impact performance on dementia tests—including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the most popular test used for determining cognitive function. In a new study published in the April 2016 Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, Lindsey Jorgensen, AuD, PhD, of the University of South Dakota and Catherine Palmer, PhD, and her colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh found that reduced audibility significantly reduces scores on the MMSE, resulting in greater apparent cognitive deficits and possible misdiagnosis of dementia.

The authors point out that, although there are no “standard” national or international guidelines for testing a person for dementia, the MMSE is used by over three-quarters of psychiatrists and has become a standard tool for front-line primary care physicians. However, research has shown that the MMSE has several structural weaknesses related to the orientation/positioning of the person being tested and their understanding of auditory language.

Previous studies have also provided evidence that hearing loss is correlated with lower performance on verbally administered tests for dementia, and alternatively, people scoring lower on cognitive status tests are more likely to have a hearing loss. In fact, hearing loss and dementia have been linked in numerous studies, with some research suggesting hearing loss is about twice as likely in people with dementia and other mental disorders compared to those with age-appropriate cognitive function. Similar studies have shown that reduced vision can also influence results of cognitive tests. Thus, it is important to reduce or eliminate confounding factors, such as hearing loss, that can affect MMSE scores and put into question its usefulness in diagnosing dementia.

In their study, Jorgensen and colleagues enlisted 125 younger (mostly 18-year-old) normal-hearing adults who were randomly placed into 5 groups with varying degrees of simulated hearing loss: 1) normal hearing; 2) mild-to-moderately severe sloping hearing loss; 3) mild-to-severe sloping loss; 4) moderate-to-severe sloping loss, and 5) severe-to-profound sloping loss. The participants were blinded relative to what level of hearing loss they were simulating, and it was confirmed that decreasing audibility significantly reduced their performance on NU-6 speech intelligibility scores.

Results showed that Groups 1 and 2 were not significantly different from each other, scoring above (28.72 and 27.64, respectively) what is considered “normal cognitive function” (?27) on the MMSE. However, Groups 3-5 had significantly poorer MMSE scores that correlated with a poorer speech intelligibility index (SII), with the cut-off in performance being around 38-40% audibility. Groups 3-5 had scores of 16.84, 10.36, and 4.2, respectively. The authors write that “the majority of participants in this study who were provided with reduced audibility would have obtained a dementia diagnosis although participants were known to be cognitively intact. Furthermore, decreasing audibility predicts more severe dementia labels.”

Jorgensen and colleagues point out that a large proportion of the older population have mild-to-moderately severe hearing loss, and 16% of the participants with this level of hearing loss in the study would have been misdiagnosed with dementia. As hearing loss worsens, the chance for misdiagnosis becomes higher.

Although the study shows that audibility alone can affect diagnosis of dementia, the authors are careful to note that older adults, who in most cases have experienced progressive hearing loss over several years, might not score the same as the younger subjects in the study. Research has shown that older adults can use context for greater accuracy in speech intelligibility.

Ultimately, the study points to the necessity for physicians and other healthcare providers to assess the auditory status of their patients and consider its potential effect on the diagnosis of dementia. This could warrant a full auditory evaluation. In some cases, the use of a personal sound amplifier to increase audibility might prove helpful. Ensuring the patient can hear and see, facing the patient, good lighting, as well as providing written versions of the test could also aid in proper diagnosis.

However, the authors caution that research suggests simply asking the patient if they have a hearing loss, in many cases, does not yield an accurate reflection of hearing status. They conclude, “The results from the present study support the need for hearing evaluation in that the degree of hearing loss and not just the presence or absence of hearing loss impacted the diagnosis…This study demonstrated that the most commonly performed test to diagnose dementia, the MMSE, is highly influenced by changes in audibility. The data from this study support the need for identification and remediation or at least consideration of hearing loss before evaluation of dementia.”

Dr Palmer told The Hearing Review, “Our next challenge is to figure out how to use these data to broadly impact practice in primary care, geriatric care, and memory clinics. We have to believe that all healthcare providers want accurate differential diagnostic results, and these data indicate that ignoring hearing status does not support accurate diagnosis. Part of this challenge is adding hearing assessment into the mix without creating greater clinical burden to the health care provider, patient, and family.” —KES

This is not rocket science people. If a DOCTOR has had a pt for any signicant time period, they know whether the pt has hearing loss or not (presence of hearing aides, having to repeat themselves during appointments, having family members state lived one has hearing loss, etc.) It should be a NO BRAINER that such auditory deficits will obviously negatively effect the results of a cogintion test that is given VERBALLY, such as the MMSE!!!!

It amazes me how in 2018, it is not a REQUIREMENT, that PRIOR to administering cognition related tests to a person who could be diagnosed with dementia, have actual documentation from that pt’s ENT, regarding results of pt’s hearing tests.

The MMSE and other such tests that measure cogition, should be required to have a medical questionaire incorporated on the form that must be filled out prior to test administration, such as:

1. Does pt show S/S of hearing loss?

If yes, indication:

A. Wears hearing aides or other listening devise

B. Has to have questions repeated often

C. Cups behind ears when listening

D. Has speaker stand closer when talking

E. Doesn’t respond to their name being called in waiting room or doesn’t respond when spoken to

F. Gets agitated in noisy environments?

G. Been recently hospitalized?

H. Any hx of head trauma?

I. Currently sick?

G. Complains of hearing problems? List below…

H. Does Pt medical records include updated records from ENT?

If yes, list

results on hearing loss below, including date of testing.

If NO— then such documentation needs to be obtained and results added to cogition test below:

I. Updated info on pts hearing evaluation.

A notation following testing should include a generic statement that addresses that cogition testing results are determined to be inconclusive due to the possibility of the reasons listed in the medical evluation given prior to exam.

An ALTERNATIVE TEST, should be avail, as a MODIFICATION accepted by and/or required under the ADA guidelines.

Why has this simple concept not been addressed or given any merit to it’s necessity?

No, I’m not a doctor, but I am a RN, and granddaughter of an elderly woman who was diagnosed with moderate dementia. Her hearing loss: 97% in left ear & 72% in right ear. She lated was deemed incompetent, yet NO MODIFICATIONS were made. Dept on Aging n Disability said they couldn’t help, since my grandmother wasn’t on Medicaid or “disabled”… It’s a shame how society treats the elderly.

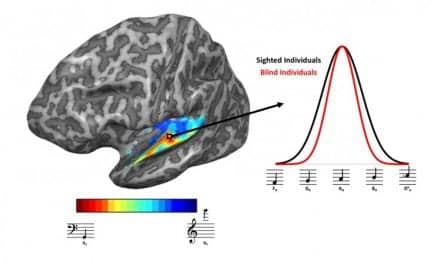

What we need to do is identify “FORGETFULNESS”, which is largely due to multitasking and mental distractions. These are not linked with hearing loss, unless information has not reached STM for processing and pass on to LTP.

Memory processing and storage begins at the pyramidal neurons within CA3, and this is also the trigger point for memory consolidation before LTP. Dementias are currently diagnosed as physiological changes in the amyloid plaques, and tangles, and Tau proteins, and may cause significant changes to the neurons. But they cannot be linked to memory functions until sufficient degradation has taken place at CA 3. In other words, biomarking does point to degeneration, but if it has only started then memory loss cannot be diagnosed.