Tech Topic | February 2018 Hearing Review

This clinical trial suggests that Signia OVP provides a substantial improvement in own-voice satisfaction, and that this improvement is present for different fitting strategies, and for different ear-canal couplings. Moreover, when the satisfaction with OVP is compared to alternative solutions from competitive products, a significant OVP advantage was seen—to the extent that own-voice satisfaction with OVP using a closed fitting is equal or superior to other products using an open fitting.

Over the years, considerable research has been devoted to studying the physical characteristics of average conversational speech, and, as a result, we have a well-documented long-term average speech spectrum (LTASS) that can be used for clinical and research purposes. When hearing aid prescriptive fitting methods are developed, the LTASS, along with the patient’s hearing thresholds, are used to determine appropriate gain and output. Decisions regarding the frequency-specific amplification of the LTASS involve consideration of several factors including audibility, loudness, sound quality, and most importantly, speech understanding. Today, we have several prescriptive fitting algorithms to choose from, both generic and those developed by individual manufacturers.

But what about when the speech of interest is not from a communication partner, but is the patient’s own voice? Because of proximity, head shadow, reflection, and refraction effects, we know that the amplitude and spectrum of the patient’s voice at his or her own ear is significantly different from the common LTASS.1 We also know that, for the patient with the typical mild-to-moderate hearing loss, the loudness of one’s voice primarily is monitored through bone conduction, not air conduction. And finally, hearing aids are programmed with the primary goal of improving speech understanding, which usually involves significant gain for the higher speech frequencies. But when we listen to our own voice, speech recognition is not a concern, as hopefully we know what the words are before the utterance. With these thoughts in mind, a reasonable conclusion would be that a hearing aid fitting optimized for processing the speech of others, is probably not optimized for the patient’s own voice. This is commonly observed by clinicians, and research has also shown that this is true.

In a large survey of audiologists on the topic of hearing aid troubleshooting issues, Jenstad et al2 reported that own-voice concerns were one of the most common post-fitting problems that required attention. The own-voice issue also was addressed in the MarkeTrak VIII survey. Kochkin3 reported that only 58% of respondents gave the rating of “satisfied” or “very satisfied” for the sound of their own voice. Recently, Høydal4 reported on a survey of nearly 400 hearing aid users; 78% had used their hearing aids for more than 2 years. The majority had mild-moderate loss, and although not stated in the report, we suspect that many, if not most, had open fittings. The participants rated their own-voice satisfaction on a 7-point scale (1=Very Dissatisfied to 7=Very Satisfied). The results revealed that the problem may be even greater than the findings of Kochkin: only 41% were satisfied with the sound of their own voice.

So, as we would expect, problems exist regarding patients’ perception of their own voice when fitted with hearing aids. This is a critical aspect of sound quality in general, and is often weighted heavily regarding initial acceptance of hearing aid use. If the user’s voice is not acceptable, this alone can prevent routine hearing use, and even lead to hearing aid rejection. If the patient does use his or her hearing aids, the negative own-voice effect might reduce confidence in their own voice (eg, “Do I really sound like this?”), and discourage vocal participation in conversations.

In the past, the clinical treatment of this problem has been fraught with negative consequences, such as turning down frequency-specific gain—which then has the unintended effect of reducing speech understanding. Some patients simply start talking softer, which also is not a reasonable solution. Yet another undesirable treatment is to fit the patient with a more open-ear coupling. While this might solve the own-voice issue, leaving the ear canal open has a negative effect on both directional and noise reduction processing—sounds that otherwise would be attenuated now pass directly to the eardrum. As a result, the patient does not have the expected signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement in background noise, which, in turn, also reduces overall satisfaction with amplification.

A Processing Solution

What is needed to solve the hearing-aid-induced own-voice problem is to have hearing aid processing that automatically changes gain and output when the hearing aid user is talking, and then instantaneously readjusts to programmed gain immediately following the utterance.5 The latest generation of hearing aids from Signia employs such processing.4,6 With a new technology called Own Voice Processing (OVP), the wearer’s own voice is detected and processed separately, while external sounds remain unaffected. That is, whenever the patient is speaking, through bilateral data sharing, processing, and analysis, the hearing aids identify this signal, and apply a dedicated setting, which differs from when only external sounds are present.

This acoustic analysis and own-voice initialization only requires a few seconds of live speech from the user while wearing the hearing aids. During this initial training, the hearing aids “scan” the acoustical path of their own placement relative to the location of the sound source. The patient’s head shape and mouth placement relative to the hearing aids are part of the sculpturing to create an accurate detection. Based on this analysis, the hearing aids are then able to detect when sound (speech) is coming from the patient, versus the surroundings, even if speech is coming from a conversational partner directly in the front. This detection is independent of vocal effort or the specific utterances of the user. (See the article by Høydal4 in the November Hearing Review for further details regarding the OVP analysis.)

Efficacy of OVP Technology

Early research with Signia OVP was very promising, showing benefit for the majority of patients fitted.4 The present study was designed to examine, in more depth, the efficacy of this new technology. In particular, four research questions related to own-voice satisfaction were addressed:

- Does OVP provide a significant benefit for the average patient for a traditional NAL-NL2 fitting using closed eartips?

- Does the fitting rationale (eg, NAL-NL2 vs Signia Nx-fit) alter the benefit of OVP?

- Does the “openness” of the fitting alter the benefit of OVP?

- Does own-voice satisfaction with Signia OVP compare favorably to satisfaction with competitive products without OVP?

The research was conducted in the Audiology Clinic of the University of Northern Colorado. The participants (n=21) all had bilateral symmetrical downward-sloping hearing losses. None had previously used hearing aids. There were 12 males and 9 females with a mean age of 67 years. The average hearing loss was 25-30 dB in the low frequencies, dropping gradually to 60-65 dB in the high frequencies.

The hearing aids used were the Signia Pure 7Nx. Following the initial fitting of the hearing aids, each participant received the OVP training. This was accomplished by having them count upwards starting at the number 21. The Signia Connexx software led the participants through the training procedure and indicated when own-voice initialization was complete, which typically required about 10 seconds. Once the OVP initialization was finished, the participants read familiar nursery rhymes aloud, and compared four different settings of the OVP: off, mild, moderate, and strong. After several short samples at all four conditions, each participant selected the setting they preferred. All participants selected either the moderate or strong OVP setting. The setting selected was subsequently used for all “OVP-On” vs “OVP-Off” comparisons for each participant.

Ratings of own-voice satisfaction were accomplished using a 13-point, 1-7 scale: 1=Very Dissatisfied, 4=Neutral, and 7=Very Satisfied. Ratings were made on a worksheet in front of the participants, allowing them to see the rating for the previous condition. The OVP-On vs OVP-Off was randomized, and the participants were blinded to the processing. For all own-voice satisfaction ratings, the participants read aloud passages of familiar nursery rhymes.

NAL-NL2 with Closed Domes

For this portion of the study the Signia hearing aids were programmed to NAL-NL2, verified with probe-microphone measures, and were fitted using closed click sleeves. Own-voice satisfaction judgements were made for OVP-On vs OVP-Off. Figure 1 shows the mean results for the two conditions (the error bars represent the 95% confidence interval). Statistical analysis of these data (two-tailed t-test) revealed a highly significant benefit for OVP-On (p<.001). As shown, the implementation of OVP produced an average increase in satisfaction of nearly two categories (“Neutral” to “Satisfied”) on the 7-level categorical scale (ie, 4.1 to 5.7).

Figure 1. Mean values for own voice processing (OVP) On vs. Off. Error bars represent 95th percent confidence intervals. Levels of satisfaction (Y-axis) are 1=Very Dissatisfied, 4=Neutral, and 7=Very Satisfied. Data shown here are for the Signia hearing aids, fitted to verified NAL-NL2 with a closed-ear dome.

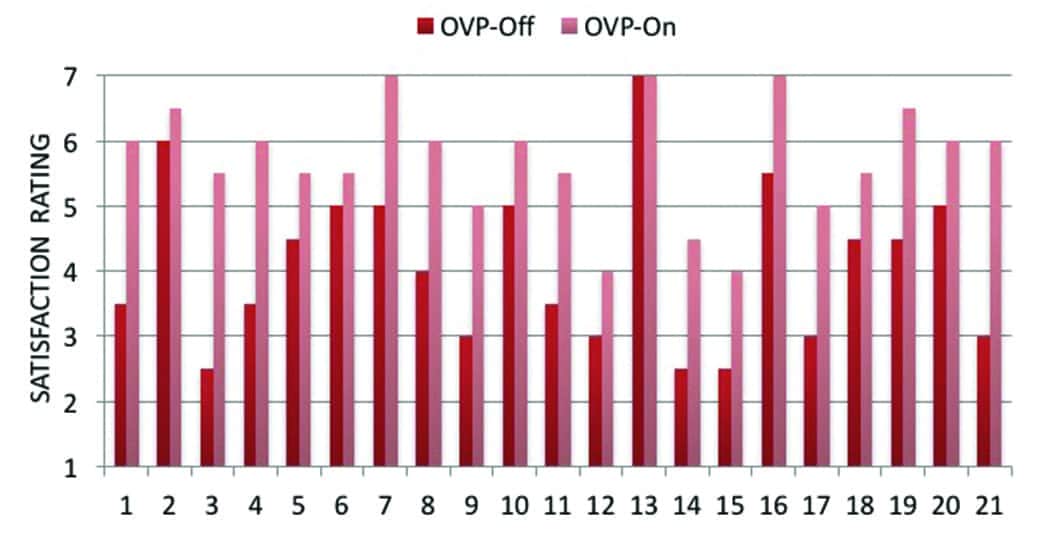

Distribution of individual ratings is shown in Figure 2. Observe that in all participants there was some increase in own-voice satisfaction, except for Participant #13, who had given the highest rating for the OVP-Off condition, and therefore, no improvement was possible. Note that with OVP-Off, 14 of the 21 participants (66%) were not satisfied with their own voice (eg, rating below #5, “Somewhat Satisfied). With OVP-On, 11 of these 14 individuals (78%) were now satisfied, resulting in a total group satisfaction of 85%. It is very possible that the 3 participants who were not satisfied with OVP-On were experiencing the occlusion effect—a condition related to bone-conducted signals traveling to the external ear canal, unrelated to hearing aid output, and, therefore, not treated with OVP.

Figure 2. Individual distribution of satisfaction for own voice processing OVP-On vs. Off. Levels of satisfaction (Y-axis) are 1=Very Dissatisfied, 4=Neutral, and 7=Very Satisfied. Data shown here are for the Signia hearing aids, verified NAL-NL2 fittings with a closed-

ear dome.

While the individual data reveal that the OVP benefit is quite robust, we questioned if there was a relationship between this benefit and other patient factors, such as age, gender, or hearing loss (pure-tone average). To examine this, we used the Spearman’s rho statistic for age and hearing loss, and the Mann-Whitney U test for gender. No significant correlations were found for any of these variables and OVP benefit.

Effect of Fitting Rationale

The NAL-NL2 is a well-recognized fitting algorithm and serves as a reliable benchmark; however, it is common for many dispensing professionals to use the Signia proprietary Nx-fit fitting method. To determine the relationship between OVP and the Nx fitting rationale, the hearing aids were reprogrammed for all participants to Signia Nx-fit. The same closed eartips and test procedures were used as for the NAL-NL2 fittings, except that no real-ear testing was conducted. Given that the Nx-fit was designed to provide the patient with an excellent “first impression” of amplification, we predicted that results for own-voice satisfaction would be improved from the NAL fittings, even for the OVP-Off condition.

For the OVP-Off condition, the Nx-fit mean satisfaction rating was 5.0. This was 0.9 higher than obtained with the NAL fitting algorithm, a significant finding (p<.001). When OVP was activated, the mean Nx-fit satisfaction rating was 6.0, significantly greater than for the same condition with the NAL fittings (p<.05). The 1.0 mean Nx-fit satisfaction rating improvement for OVP was also significant (p<.001).

With OVP-On, 95% of the participants had a satisfaction rating of at least #5 (“Somewhat Satisfied”), whereas only 71% reached this satisfaction level with OVP-Off. Most notably, with the processing on, only 3 individuals had a rating below #6 (“Satisfied”).

Effect of Open Fittings

To this point we have discussed the clinical findings for OVP for hearing aid fittings using a closed fitting dome. In routine practice, we know that many, if not most, patients are fitted with coupling tips that are vented or open. Is OVP also beneficial for these patients?

Before we discuss our results regarding this topic, it is important to point out that just because the fitting is open, own-voice issues still exist, as we mentioned earlier, associated with the research of Høydal.4 We often think of own-voice issues being related to the occlusion effect, and in these cases the patient might report that their voice sounds hollow, booming, too-much-bass, etc. Indeed, it is probable that an open fitting will reduce these own-voice issues. But dissatisfaction with one’s own voice can take on many other forms. As part of this study, before the initial OVP-Off ratings were made, the participants were asked to describe what it was that made their own voice less than satisfactory. A common response was simply “unnatural,” but 40% of the participants used terms like tinny, sharp, or too treble. These are negative attributes that likely also will be present with open fittings.

For this part of the study, we examined two different types of more open fittings with the hearing aids programmed to Nx-fit: a vented click sleeve and an open fitting tip. Satisfaction ratings for the participant’s own voice were conducted as before. The findings for the different fittings are shown in Figure 3, as well as the results for the Nx-fit closed fittings discussed in the previous section.

Figure 3. Mean values for own voice processing (OVP) On vs. Off for three different types of ear-canal coupling: closed, vented, and open. Error bars represent 95th percent confidence intervals. Hearing aids fitted to Signia Nx-fit. Levels of satisfaction (Y-axis) are 1=Very Dissatisfied, 4=Neutral, and 7=Very Satisfied.

Statistical analysis revealed that OVP provided a significant improvement for both the vented (p<.001) and the open (p<.01) fittings. As shown in Figure 3, there was no difference between the mean ratings for closed and vented fittings for either OVP-On or OVP-Off. While it might be expected that a vented coupling would provide somewhat better own-voice ratings, we suspect that the similarities in the findings were due to slit leak for the “closed” click-dome fittings—that is, there was already some venting present.

From a clinical standpoint, it is important to note that Nx-fit/closed with OVP-On is better than Nx-fit/open with OVP-Off (p<.05), and equal to Nx-fit/open with OVP-On (p>.05). As we mentioned earlier, one method to improve the own-voice issue is to fit the patient with a more open ear-canal coupling. We know, however, that opening the ear canal gives unwanted background noise a direct pathway to the eardrum, making both directional processing and noise reduction less effective. As shown here, if OVP is implemented, the same desired own-voice qualities of an open fitting can be achieved with a closed fitting. For both conditions, 95% of the participants were satisfied with their own voice (a rating of #5 or higher).

As we would expect, the benefit of OVP is slightly reduced for open fittings, simply because the initial satisfaction is higher, and there is less room for improvement. If we look at the different levels of satisfaction, however, we do see substantial individual benefit. For example, the percent of #6 or higher ratings with OVP-Off were 57%, whereas this increased to 81% with OVP-On. Our suggestion to clinicians is that, even when a patient says that his or her voice sounds “okay,” provide them the option of listening with OVP-On, as “okay” might just become “excellent.” For example, one of the participants rated her own voice #7 (Very Satisfied) with OVP-Off. When she listened to her voice with OVP-On, she immediately exclaimed “Well that’s a 10!” (the rating chart only went to #7).

Comparison to Competitive Products

We have presented research showing a significant benefit for OVP that is consistent across fitting algorithms and different ear canal couplings. Our comparisons have focused on OVP-Off vs OVP-On for the Signia Nx product. It is reasonable, however, to also compare the OVP findings to competitive products, and this also was part of the current research. The premier product (October, 2017) of two leading competitors was used, and the own-voice satisfaction ratings were conducted in the same manner as with the Signia product.

For the “closed” fitting tests, the recommended closed eartips from each manufacturer were used. Given that the tips from one manufacturer might be more open or closed than another, and that this could possibly influence the satisfaction ratings, a real-ear occluded response (REOR) was conducted for each ear for all participants for the closed fittings for the three different brands. The real-ear occluded gain (REOG) across frequencies averaged around -1 dB for all three brands, with no significant difference at any frequency, suggesting an equal “tightness of fit” among manufacturers.

For the closed fittings, the products were fitted to NAL-NL2 with real-ear verification (to make a direct comparison to the Signia data shown in Figure 1). For the open fittings, the manufacturer’s recommended open-fitting tip was used, and the hearing aids were programmed to the manufacturer’s proprietary fitting. The own-voice satisfaction ratings for the two competitors are shown in Figure 4, along with the previously discussed satisfaction ratings for the Signia product with OVP-On.

Figure 4. Mean values for own-voice satisfaction for closed and open fittings for Signia and two leading competitors. Error bars represent 95th percent confidence intervals. Closed coupling data were verified NAL-NL2 fittings; open fittings were each manufacturer’s proprietary algorithm.

Figure 5. Distribution of percent of participants with an own-voice satisfaction rating of #5 (Somewhat Satisfied) or higher for Signia and two leading competitors. All products were fitted using closed domes to the NAL-NL2 prescriptive method.

Statistical analysis of these data reveal higher satisfaction ratings for the closed condition for Signia compared to both Competitors A and B (p<.001). For the open fitting condition, there also was a significant advantage (p<.05 for Competitor A; p<.001 for Competitor B). What is also an important finding, from a clinical standpoint, is that the Signia Nx-fit closed (Satisfaction rating 6.0, see Figure 3) is equal to the open fitting of Competitor A, and superior to the open fitting of Competitor B (p<.001).

Figure 5 summarizes individual satisfaction ratings for the three manufacturers for the closed condition, with all products programmed to the NAL-NL2 fitting algorithm. The percentages shown represent participants with a satisfaction of “Somewhat Satisfied” or higher. The individual benefit of OVP is clearly shown; the NAL-NL2 satisfaction rate for Signia was 86%, whereas satisfaction was only at 33% for the other two manufacturers.

Figure 6. Distribution of percent of participants with an own-voice satisfaction rating of #6 (Satisfied) or higher for Signia and two leading competitors fitted according to the manufacturer’s proprietary algorithms. Signa was fitted with closed domes, whereas competitors were fitted open.

As we mentioned earlier, when proprietary algorithms were used, group statistical analysis revealed that own-voice satisfaction for Signia-OVP with a closed fitting was equal to or better than that of the competitors with an open fitting. We also examined this on an individual basis, as shown in Figure 6. For this comparison, we identified participants who, when fitted with each manufacturer’s proprietary fitting, had an own-voice satisfaction rating of either “Satisfied” or “Very Satisfied.” Importantly, the Signia data are for a closed fitting; the data for the competitive products was obtained with an open fitting. As shown, a large difference in individual rate of satisfaction was observed—86% for Signia compared to 58% and 37% for the two competitors.

Summary and Conclusions

Every year we see new features introduced by most major hearing aid manufacturers. It’s not often that the features change the way we fit hearing aids. We believe the Signia OVP does. Patients’ annoyance with their own voice when fitted with hearing aids is a real problem, and, until now, we haven’t had an efficient solution. Turn down gain? That reduces speech understanding. Use a more open fitting? That reduces the effectiveness of directional technology and digital noise reduction. Tell them that they will “get used to it?” They usually don’t.

This clinical trial revealed that Signia OVP provides a substantial improvement in own-voice satisfaction, and that this improvement is present for different fitting strategies, and for different ear-canal couplings. Moreover, when the satisfaction with OVP is compared to alternative solutions from competitive products, we see a significant OVP advantage—to the extent that own-voice satisfaction with OVP using a closed fitting is equal or superior to other products using an open fitting.

Improving satisfaction with one’s own voice will encourage the acceptance of amplification, and increase hearing aid use. The need to troubleshoot own-voice issues will be reduced, requiring less clinical visits. Having a natural sounding voice will encourage communication and social interaction. Having a more closed fitting will improve the benefit of directional technology and noise reduction, potentially improving speech recognition. All this is good.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Powers at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Powers T, Froehlich M, Branda E, Weber J. Clinical study shows significant benefit of own voice processing. Hearing Review. 2018;25(2):30-34.

References

-

Pittman AL, Stelmachowicz PG, Lewis DE, Hoover BM. Spectral characteristics of speech at the ear: Implications for amplification in children. J Sp Lang Hear Res. 2003;46[Jun]:649-657

-

Jenstad LM, Van Tasell DJ, Ewert C. Hearing aid troubleshooting based on patients’ descriptions. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14(7):347-360.

-

Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: Consumer satisfaction with hearing aids is slowly increasing. Hear Jour. 2010;63(1)[Jan]:19-32.

-

Høydal EH. A new own voice processing system for optimizing communication. Hearing Review. 2017;24(11)[Nov]:20-22.

-

Ricketts TA, Bentler R, Mueller HG. Essentials of Modern Hearing Aids: Selection, Fitting, and Verification. San Diego: Plural Publishing;2019.

-

Froehlich M, Powers TA. Sound quality as the key to user acceptance. November 27, 2017. Available at: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/sound-quality-as-key-to-21621

Hello sir,

Would like to see the satisfaction checklist used in the research.

Thank you.

Hello, I have been wearing different hearing aids of the expensive range and now being 80 I need stll more amplification.

My primary interest is not comprehending language (I would of course welcome any improcvements there!) but listening to music at home (all kinds) and in at least 10 concerts (classical) per year.

I wear BTE with vented otoplasts because I hear low frequeny inputs quite well but need all amplification I can get, increasingly in the above 2 to 8K range. My venting openings and some slit losses(e.g when chewing) result in a high risk of feedback.

As I now need even more amplification I am looking for the best feedback suppression achievable because I love the vented systems.

Should that not be possible I would like to try OVP just to see wether higher amplification can be achieved with closed otoplasts and no lack of fidelity of the music. By the way: Classical concerts are visited by grey hair fans of which at least 60 to 80 % are wearng hearing aids. But so far nearly all the ingenuity and research has been invested in improving speech comprehension!

Once you are out of the daily treadmill the interest shifts more to leisure! And more and more elderly people would love to get better music reproduction.

Best regards

Hartmut Uhr

I would appreciate if you could inform me from where I could.get this OVP service in sri lanka

Hello,

If you use the hearing store locator then there is a clinic listed in Sri Lanka with contact details.

https://www.signia-hearing.com/store-locator/