Patient Care | August 2021 Hearing Review

Balancing compassion with professional demeanor amidst the pain of hearing loss and tinnitus

By Michael A. Harvey, PhD, ABPP

By understanding the inner workings of empathy, we can reap its benefits and avoid its perils; we can accept the personal wisdom and growth from bearing witness to our patients’ struggles—without all the negative effects of vicarious trauma.

A hearing care professional recently told me, “My patient gave me an intimate glimpse of what it’s like to lose your hearing. Like how he feels like an imbecile and stupid for missing words and conversations, continually feeling short-changed personally and at work, and constantly feeling lonely and cut off from people. The problem is I can’t stop thinking about him—even in my sleep. He told me things he’s never told anyone before, feelings that came straight from his soul. It was a sacred trust.” Sue, the hearing care professional (HCP), replayed that patient visit for over 10 minutes and then concluded, “I’ve heard many versions of this before, but somehow it’s hitting me like a ton of bricks. It’s taken over my life!” Tears streamed down her face.

An amazing but not surprising phenomenon. Sue bearing witness to her patient’s narrative is both an ordinary and extraordinary process. It is statistically ordinary because, as Sue said, versions of that narrative are commonplace and are often shared with the HCP. As Clark and English1 noted, “To gain an appreciation of what has led patients to our offices we need to allow them to share their stories and guide them through a reflection of the personal impact of hearing loss.” However, inasmuch as a patient’s reflection comes “straight from one’s soul,” the process of sharing it with the HCP is also extraordinary. It often triggers a slew of raw, private emotions—an affective eruption—that may blindside both the patient and HCP.2

Admittedly, it’s a heck of a lot easier to focus on anything but this sacred soul stuff (eg, the audiogram. or hearing instrumentation). However, what may be easier for the practitioner may not be the most beneficial for the patient. As one patient put it, “The reason I asked Dr Smith to fit me with hearing aids is he was the first person to ask me how I was feeling about my hearing loss and who truly wanted to hear my answer.”

However, this article is not about how counseling-infused audiologic care affects the patient which has been skillfully written about elsewhere.1 Rather, this article focuses on how this approach affects us.

Trauma is contagious. It is frequently impossible to compassionately assist people who have suffered a major loss without somehow being changed. It has been described as the cost of caring.3 In the words of Czech author, Milan Kundera:

“There is nothing heavier than compassion. Not even one’s own pain weighs so heavy as a pain with someone and for someone, a pain intensified by the imagination and prolonged by a hundred echoes.”

Stated more precisely, those who bear witness to another’s traumatic hearing loss may experience vicarious trauma (VT): a psychological transformation in the helper’s inner experience resulting from empathic engagement with the patient.

The helper becomes vulnerable to a variety of post-traumatic stress reactions that may feel like being hit with “a ton of bricks.” In contrast to burnout, which typically emerges gradually and is a result of emotional exhaustion, vicarious trauma can emerge suddenly with little warning.4

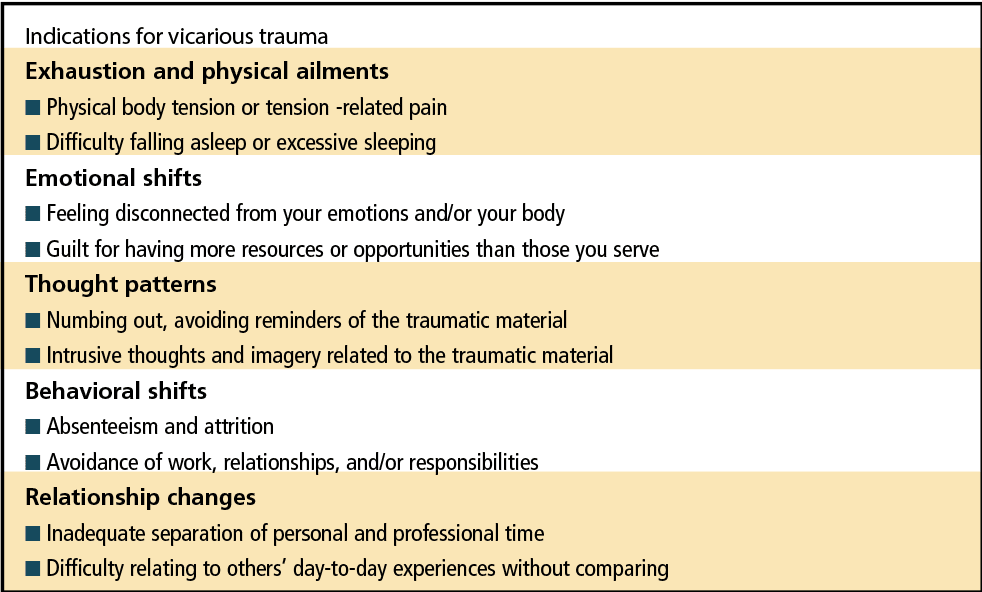

Moreover, VT is not limited to helping professionals. As I write this article, the news is airing the Derek Chauvin trial, filled with heart-wrenching footage of those who had witnessed the murder of George Floyd. Their vicarious trauma is replete with recurring nightmares, flashbacks, helplessness, guilt, and horror. (See Table 1 for common signs of vicarious trauma.)

Vicarious trauma is not related to poor psychological health; it is a common reaction to witnessing another’s pain. However, as I will explain, if managed properly, VT has potential benefits for the practitioner. In order to understand its risks and benefits, we must understand the sine qua non of VT: one’s capacity for empathy.

The Dual Components of Healthy Empathy

Empathy is defined as “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” Sounds simple enough, but the psychological mechanisms of healthy empathy involve a tenuous internal balancing act. In order to avoid the danger and reap the benefits of empathy, one must balance its emotional and cognitive components.5

Metaphorically, the emotional component is putting yourself in another person’s shoes, but losing yourself in the process—psychological fusion. This blurring of boundaries which encompasses too much of the emotional component of empathy is a common cause of VT for helping professionals. Typically, one feels taken over by intrusive thoughts and imagery related to the traumatic material, aptly referred to as affective drowning. For example, Sue, the HCP, reported “The problem is I can’t stop thinking about him, even in my sleep.”

Often, one’s own traumatic memories get triggered. As documented by the seminal Adverse Childhood Experience Study, one 1 of 6 adults have experienced at least four significant childhood adverse experiences, such as abuse, neglect, significant loss, and exposure to violence.6 For example, a HCP reported that he couldn’t stop ruminating about a patient who experienced repeated bouts with cancer. Previously pleasurable activities became ominous and he had recurring nightmares of becoming ill. Not coincidentally, his mother had died of cancer during his childhood.

This is where the cognitive component of empathy becomes important. Whereas the emotional component of empathy has to do with merger and symbiosis—“I feel your feelings, think your thoughts”—the cognitive component has to do with disengagement, with holding onto your sense of self as distinct from another.5 It is our metaphorical shield.

For example, Sue reported that she found herself tapping her knee when feeling sucked into her patient’s pain. It was her tactile way of grounding herself. In another setting, a gastroenterologist lamented that he couldn’t interrupt his patients when they would go “on and on about their suffering” so he came up with a cognitive grounding strategy: “I would listen long enough to make a diagnosis, and then I would go skiing.”

What happens when we shift too much into the cognitive component of empathy? In marked contrast to Milan Kundera’s statement that “There is nothing heavier than compassion,” we hide our faces in the sand. We reduce piercing, iridescent vicarious pain to a gray, dull ache; however, in the process, we become non-feeling machines. Thoughts replace feelings. We tell ourselves it’s a small price to pay, as we revel in never having to ever again agonize over another’s sorrow.

This experience is referred to as compassion fatigue: becoming tired of caring. We disengage emotionally from patients via a shell of protective numbness.3 As one oncologist put it, “I never thought I’d dehumanize my patients as disease entities, but after witnessing so many deaths, I’m tired of caring!” Likewise, a sign language interpreter recalled that “When I first witnessed the oppression of people with hearing loss, I was appalled, but after a while—and I’m ashamed to say this —I sort of got used to it. You ask me about empathy! What’s that? I have no empathy!”

Interestingly, a woman with tinnitus, who I will call Mary, articulated this dynamic after she met with an otolaryngologist who, in her words “made no eye contact with me. When I asked questions, his answers were very blunt, stoic, and unfiltered with little to no compassion.” As I discussed in a previous Hearing Review article,7 her homework was to write a letter to that doctor that she may never send and then to write an imagined letter the physician might write back to her. This is an excerpt from her imagined letter:

Dear Mary: Thank you very much for your heartfelt note that I’m sure was very difficult to write. I’m so sorry for my lack of bedside manner with you in my office. I didn’t mean any disrespect and you’re right —I have never had tinnitus so I can’t know exactly how you feel. But over many decades of practice, I’ve heard countless patients tell me, as you aptly put it, what a difficult diagnosis it is to bear. I’m not making excuses, but frankly, after a while, it gets to me. I became a doctor to help people and with tinnitus sufferers, my ability to help doesn’t feel adequate. To put it bluntly, it feels shitty. And with you, and unfortunately with some other patients, I’ve often found myself just going through the motions. Mary, thank you for your letter which jarred me out of that numbness of helplessness and woke me up to a realization that I have underrated the benefits of compassion. I’m extremely grateful to you.7

Tools to Mitigate the Risks of Vicarious Trauma and Reap Its Benefits

So the essential question becomes: How do you protect yourself from the costs of caring for patients while reaping the benefits? There are many self-care tools that outline strategies of mitigating the negative effects of VT, such as being attuned to one’s needs, limits, emotions, and resources; maintaining balance among activities like work (especially), play, and rest; and maintaining positive familial and social relationships. I will not elucidate these tools as they are well documented in the literature. I recommend the interested reader to Saakvitne and Pearlman (1996)8 and Meichenbaum (1994).9

Perhaps the most important recommendation for HCPs to manage VT is to acknowledge it. Just as we advise those with hearing loss not to wait 7 years or more until getting treatment, we should not shield ourselves behind a wall of denial by not acknowledging our VT. There is no need for shame. To re-iterate, it’s the cost of caring, an occupational hazard. For those of us who have the psychological capacity for experiencing compassion and empathy, it’s not if we experience VT, it’s when.10

Balancing the dual components of empathy—the “I feel your feelings” with “I am still me”—is easy-to-say but often hard-to-do, particularly in times of stress and when our own psychologically traumatic memories get triggered. One HCP admitted that he experienced flashbacks to his father being killed in an automobile accident when treating a male patient with a similar medical history. The task was to regain his empathic balance. The HCP said, “I really connected to this patient, but when it got too much for me, I would go over my shopping list.” That was his version of the gastroenterologist’s internal ski trips.

Of course, most of us would be upset to learn that our doctor is on a ski trip or reviewing a shopping list during our appointments. However, it is not an all-or-nothing occurrence. Hopefully, our healthcare practitioner is balancing attending to our needs with proper self-care that is not focused on us.

Often, but not always, that balance between empathic flooding and empathic drought occurs naturally. When we slip into habitually protecting ourselves with our own version of “shopping lists,” for one reason or another—and much of the time we don’t know exactly what hit us—the intensity of another’s pain hits us like a ton of bricks.

The Benefits of Vicarious Trauma

There has been developing literature on what is termed post-traumatic growth which presents how people may benefit from traumatic experiences. Individuals who face trauma may be more likely to become cognitively engaged with fundamental existential questions; to value the smaller things in life more and also to consider important changes in the religious, spiritual and existential components of life.

One audiologist described how experiencing vicarious trauma in her practice has given her life more contrast and texture:

“For a very long time, I couldn’t get my patient, Mr Olson, out of my head. He offered me a glimpse of his being tortured by unrelenting tinnitus that I’ll never forget. I witnessed him trying treatment after treatment and then how he eventually came to terms with his condition. Looking back on this, I feel very lucky to have met him in this intimate way.

“Sharing in the growth and development of another person as they cope with hearing loss is an honor, a life-altering, spiritual experience for those who are open to it. Our patients’ resilience promotes our increased respect for the human spirit.

“We have the experience of knowing intimately people we would otherwise not have known, and of sharing vicariously in others’ life choices and struggles, their most intimate feelings, needs, and concerns which get sparked by their loss of hearing. Our connections with patients through humor, love, and pain contribute enormously to our growth as individuals, add complexity to our lives, and increase our capacity for empathy and understanding.

“At times we have had glimmers of wisdom resulting from our work. Our patients teach us the things we might have learned from grandparents, wise elders. Sharing joy and sorrow, laughter and pain, wisdom and ideas with another person is at the heart of what it means to be human.”

The changer and the changed. There is a Buddhist saying that when the student is ready, the teacher will come. For our present discussion, the HCP is the student while the patient is the teacher.

By understanding the inner workings of empathy, we can reap its benefits and avoid its perils; we can accept the personal wisdom and growth from bearing witness to our patients’ struggles.

If you ask me, it’s a pretty good deal that we get paid for learning from our patients about what it means to be human.

References

- Clark JG, English KM. Counseling-infused Audiologic Care. 3rd ed. Inkus Press; 2018.

- Harvey MA. The transformative power of an audiology visit. Hearing Journal. 2000;53(2):43-47.

- Figley CR. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder In Those That Treat the Traumatized. 1st ed. Routledge; 1995.

- McCann IL, Pearlman LA. Psychological Trauma and the Adult Survivor: Theory, Therapy, and Transformation. 1st ed. Brunner/Mazel; 1990.

- Jordan JV, Kaplan AG, Miller JB, Stiver IP, Surrey JL. Women’s Growth in Connection: Writings from the Stone Center. 1st ed. The Guilford Press; 1991.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html. Published April 6, 2021.

- Harvey MA. How can we help patients with tinnitus when we don’t have a cure? Hearing Review. 2021;28(2):22-24.

- Saakvitne KW, Pearlman LA. Transforming the Pain: A Workbook on Vicarious Traumatization. 1st ed. W. W. Norton & Company; 1996.

- Meichenbaum D. A Clinical Handbook/Practical Therapist Manual for Assessing and Treating Adults with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. 1st ed. Institute Press; 1994.

- Meichenbaum D. Self-care for trauma psychotherapists and caregivers: Individual, social, and organizational interventions. Melissa Institute handout. https://melissainstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/SELF-CARE-FOR-TRAUMA-PSYCHOTHERAPISTS-AND-CAREGIVERS-changed-26.pdf. Published 2007.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Dr Harvey at: [email protected].

Citation for this article: Harvey MA. The changer and the changed: the perils and benefits of empathizing with our patients. Hearing Review. 2021;28(8):34-36.