Established in 1975, Precision Laboratories has built a strong reputation by offering its clients quality, custom-made ear molds that are handmade by industry craftsmen.

All the research and design ingenuity in the world does a hearing aid no good if, in the end, it is connected to a coupler of poor quality. For nearly 30 years, providing quality couplers in the form of supremely comfortable custom ear molds has been the mission of Precision Laboratories in Altamonte Springs, Fla, a small but important company seen by some independent audiologists and hearing-aid dispensers as an essential factor in their success.

The company’s basic value-proposition goes like this: a provider casts an impression of the client’s ear, from which Precision Laboratories then creates a customized coupler ideally suited to the particular hearing system the provider has chosen.

“In our role as a support laboratory, we strive to be problem-solvers first and foremost in order to deliver a fine product on time and at a reasonable price,” Lassiter asserts.

Hand-Made Product

The company sells primarily to audiologists and hearing aid dispensers, although found among its customer base these days are more than a few law enforcement agencies, airlines, industrial concerns, and others in need of top-notch devices to attenuate noise for the health protection of employees.

Sales activities for the most part are confined within the borders of the United States. The company has gone abroad in the past, but found the logistics of supplying custom product offshore to be too daunting to make such transactions practical. Besides, “we’re so busy here at home that we don’t really need to go anywhere else,” Lassiter offers.

Significantly, custom ear molds prepared by Precision Laboratories are made the old-fashioned way—by hand. However, the labor-intensive nature of the work means it is hard to hurry the process, says Lassiter in explaining that it is not efficiency but proficiency that counts in an operation like his.

“One of the reasons customers like buying from us is the craftsmanship that we put into each and every one of our products,” he contends. “We have a very highly skilled production team. They’ve been doing this kind of work a long time.”

| Well-Versed in Hearing Protection

Precision Laboratories, Altamonte Springs, Fla, has no direct involvement with local, state, or federal legislative bodies and regulatory agencies that develop rules concerning noise—either to limit or abate it. However, the company is well versed in workplace regulations with regard to hearing protection. It is on the basis of that knowledge that Precision Laboratories makes custom noise-attenuation products for its various customers outside the hearing industry. The most oft-referenced requirements for office and factory hearing protector devices (HPDs) are those set forth by the US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety & Health Administration, in its occupational noise exposure rules, Part 1910.1 Key elements of OSHA Part 1910 are as follows:

Also frequently referenced are guidelines that come from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.1 Unlike OSHA regulations, which must be obeyed, these are merely recommendations. They include the suggestion that:

—Rich Smith Reference |

Lassiter calculates 75% of his employees (there are 25 en toto) have put in 10 or more years with Precision Laboratories. Such loyalty helps explain why the company runs as smoothly as it does. Of course, it doesn’t hurt matters any that Precision Laboratories is a family owned-and-operated business: actively involved in the day-to-day routine are Lassiter’s wife, son, and daughter, plus his children’s spouses.

Ever a challenge for Precision Laboratories is the task of getting itself up to speed as quickly as possible any time a new technology debuts—which, these days, is often. As an illustration, Lassiter points to the company’s recent experience in response to one manufacturer’s release of a hearing product featuring a flexible venting mechanism.

“The vendor asked us to become an authorized support lab for this product,” he says. “We were given samples to examine, along with a detailed technical briefing from the manufacturer. After that, it was up to our ear mold crafters to develop the right solutions. Soon enough, they did.”

Precision Laboratories’ current marketing is built on a strategy of selling by phone, advertising in trade magazines, engaging in direct mailings, and exhibiting at industry shows. A sizable slice of new orders come about as a result of favorable word-of-mouth spread from satisfied customers to colleagues and peers.

“The most important thing we believe about outreach is that, no matter what kind you do, you’ve got to make sure you can deliver what you promise,” Lassiter says. “If, for instance, you pledge good service, you’ve got to have in place—as we do —a strong customer-support system.”

Colorful Past

Precision Laboratories has grown at a steady clip almost every year it has been in business. It was started in 1975 by Lassiter and a former boss of his, Jerry Blue, who owned an Oklahoma City-based ear mold laboratory (Lassiter held a management position with that laboratory and had been an employee almost since its inception a decade earlier). That year, a mutual friend working as a sales representative for a hearing aid manufacturer in Orlando mentioned to Blue and Lassiter that the Central Florida region was brimming with opportunity for ear mold makers, since there were so few there at the time. That is all Blue and Lassiter needed to hear. The entrepreneurial-driven pair packed their belongings and headed for Orlando to try replicating their Sooner State success.

“We opened with lots of optimism, and not much else,” Lassiter recalls.

A big part of the lure for Lassiter in leaving Oklahoma to set up shop in Florida was the chance to actually co-own a venture in the field he loved. Then, too, there was the allure of the climate: near year-round sunshine and warmth (precisely the kind of conditions preferred by your typical motorcycling enthusiast, which Lassiter was and is—for the record, he drives a Harley-Davidson).

In preparing to open for business as Precision Laboratories, Blue and Lassiter took the step of hiring a sales representative of their own—none other than the friend who had induced their transplantation with his reports of opportunity aplenty in the Orlando market.

“He had good relationships with the region’s hearing aid manufacturers, and we thought we might be able to capitalize on those by having him on board with us,” says Lassiter.

It was a good strategy. Not long after the ribbon-cutting, the fledgling operation began thriving.

Initial products offered were custom ear molds and accessories (including impression materials and grinding tools). Much later, in 1989, Precision Laboratories acquired a small company—Fisher Technology, a hearing aid repair business with four employees. This purchase allowed Precision Laboratories to qualify as a full-service laboratory, of which there were precious few regionally. It also set the stage for a surge of further growth: with the undergirding of Fisher Technology, Precision Laboratories was able to design and build behind-the-ear hearing instruments, thereby entering an entirely new arena—the first of several.

Jumping at Opportunities

Lassiter took the reins of Precision Laboratories in 1992 when he bought out his partner Blue, in accordance with an exit agreement they had penned back when the company was formed.

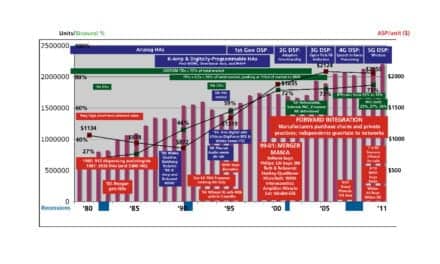

Within a few years, though, sales of BTE instruments slumped as new technologies—chiefly miniature in-the-ear hearing instruments—swamped the market. Precision Laboratories counter-punched in 1998 by branching into ITE and one-size-fits-all, in-the-canal hearing instruments. These were marketed as generic starter aids. At about the same time, the company trotted out a line of custom instruments under the brand Precision Ear.

Markets outside the hearing aid business were explored as well. Drawing on the expertise gained from the production of custom ear molds and hearing instruments, Precision Laboratories came up with wireless communications headsets designed specifically for use in automotive track racing to enable drivers and their pit crews to talk to one another over the deafening roar of the engines. The company subsequently adapted this technology for use as monitoring devices by music industry performers and sound-system operators. From there, it introduced custom and generic lines of noise attenuators—the most popular of which target the hearing-protection needs of shooters on the firing range (others are sold to airlines and to industry at large).

Also much in demand from Precision Laboratories were sonic valve protectors that allow exposure to noise only up to a user-defined decibel count before finally shuttering the ear.

“We can’t claim credit for designing these valves,” says Lassiter. “We procured them from a manufacturer and then incorporated them into our attenuators.”

But what the valves product demonstrates is Precision Laboratories’ agility.

“When we see a market opportunity, and if we feel there’s a need we can satisfy, we don’t hesitate to leap on it,” Lassiter assures.

One opportunity the company weighed but then waived centered around amplified products.

“We felt that with those we’d be straying a little too far afield,” says Lassiter.

Many new-product opportunities are brought to Precision Laboratories by end users in search of a solution.

“For example, we became involved with hearing protection for shooters after a local police department came to us with a request for really good noise attenuators for use on their practice range, attenuators better than what was available commercially,” he tells.

Lassiter insists that the opportunities that have come his way are often the same ones available to other types of providers.

“I’m seeing more and more health care professionals—audiologists in particular—who are realizing the potential that’s out there in these nontraditional markets,” he says. “And, as they realize it, we’re going to be there to supply them with the products to help them develop a foothold of their own.”

Even so and in spite of all the diversification, Precision Laboratories has never departed from its original focus—custom ear molds.

“In 2004, we felt the need to sell off our hearing aid repair and Precision Ear divisions so we could commit our total support to our growing custom ear mold, accessory, and special products divisions,” Lassiter says.

If trends continue apace, Precision Laboratories 5 years from now should be bigger and more successful in its niche, he predicts.

“Market conditions are favoring the industries and product lines we’re in,” Lassiter points out. “All things considered, we think ours is a formula that should ensure continued growth for us in the years to come—and continued success for our customers.”

Rich Smith is a contributing writer for Hearing Products Report.