By Karl Strom, editor

One of my tasks this week was to write about my first real-life experience with a remote at-home hearing aid fitting with the new Phonak Paradise hearing aid. My experience with remote fitting was extremely positive, but before I write about it, I’d like to address the topic of hearing aid sound quality—and take you in the Wayback Machine to a boat ride 20 years ago. This is because the sound quality of the Phonak Paradise hearing aid was a revelation for me: I think something new and very important is occurring in hearing healthcare.

Now, to the boat trip. Sometime in the late 1990s, I was attending a hearing conference in Fort Lauderdale and took an evening boat excursion with some industry friends. On the boat was the owner of a relatively small but well-regarded hearing aid company who was extremely excited about their latest hearing aid. He couldn’t wait for me to try them so I could experience their amazing sound quality firsthand. We programmed them right there on his computer for my flat (admittedly milder-than-today) hearing loss and I put them on. I remember having to feign enthusiasm; indeed, the hearing aids did have a cleaner sound than most, but in truth, they still sounded like 1990s hearing aids—which is to say they sounded pretty electronic and unnatural.

As an editor of a hearing healthcare trade journal for over 25 years, I’ve probably listened to hundreds of hearing aids. While today’s latest open-fit hearing aids still come up slightly short on what an audiophile would probably call true high-fidelity sound quality (and there are some technical/trade-off reasons for this that I won’t get into), the more recently introduced RIC hearing aids—including the new Audéo Paradise and its predecessor Audéo Marvel, as well as several other hearing aids introduced in the past 2 years—are far better in sound quality than what was offered just 5 years ago, and light years better than those 1990s devices.

Why is this important? Because a person like me with a mild hearing loss (eg, a 20-25 dB flat loss through 4 kHz, dropping off to a moderate loss at 6-8 kHz) usually has only situational amplification needs. And, if poorer sound quality makes the device acoustically noticeable in any appreciably bad way, then it’s just not worth the trade-off to wear a hearing aid except for special situations like watching TV with my better-hearing wife and kids. So, sound quality matters a lot to people with milder hearing losses. (In fact, my friend and frequent HR contributor, Mead Killion, PhD, has argued for decades that sound quality is a lot more important for all hearing-impaired consumers than most audiologists and industry engineers think it is. But that’s a topic for another blog.)

The bottom line is this: the sound quality of these new hearing aids is so impressive that I can see how it would be beneficial for people with mild losses to wear them all the time. Because I have a “borderline hearing loss,” my audiological results from a pure-tone audiogram, speech-in-noise (SIN) test, and needs assessment would probably indicate that I don’t require a hearing aid right now—and the professional should definitely tell me that. However, these aids do give me a distinct benefit. Although I don’t need them according to standard audiological guidelines, I’d still consider buying them.

The fact that these new hearing aids are acoustically transparent for a person with a slight hearing impairment has huge ramifications. Younger users can benefit from the selective amplification of this hearing aid without having to compromise on natural sound quality. And the Bluetooth streaming, phone answering, and Siri features are extremely cool and handy. For example, I can place a phone call to my wife without touching my phone by double-tapping my right ear and telling Siri, “Call Christine Strom.” I can listen to the ballgame while walking through Target, and quickly turn off the broadcast when I meet someone by discreetly tapping again on my ear. I can even ask Siri how many homeruns Harmon Killebrew had in 1969 and she’ll tell me the answer (49) without anyone else hearing it.

Upcoming features in hearing aid manufacturers’ product development pipelines are even more impressive. At the Phonak Paradise launch, the company’s VP of Audiology Stefan Launer made an offhand mention of just a few: Research on how voice might serve as an early warning indicator to check on health or gauge emotional status; sensors that might monitor heart rate, blood pressure, or assist in fall prevention; language translation and real-time captioning. He’s certainly not the first to mention these, and some companies have already started employing some of these features. It’s now pretty well established: the ear is going to be the intersection for communication and health (and more)—and that makes it a very large and important crossroad.

Overcoming Challenges in Gaining Access to Younger, Milder-Loss Users

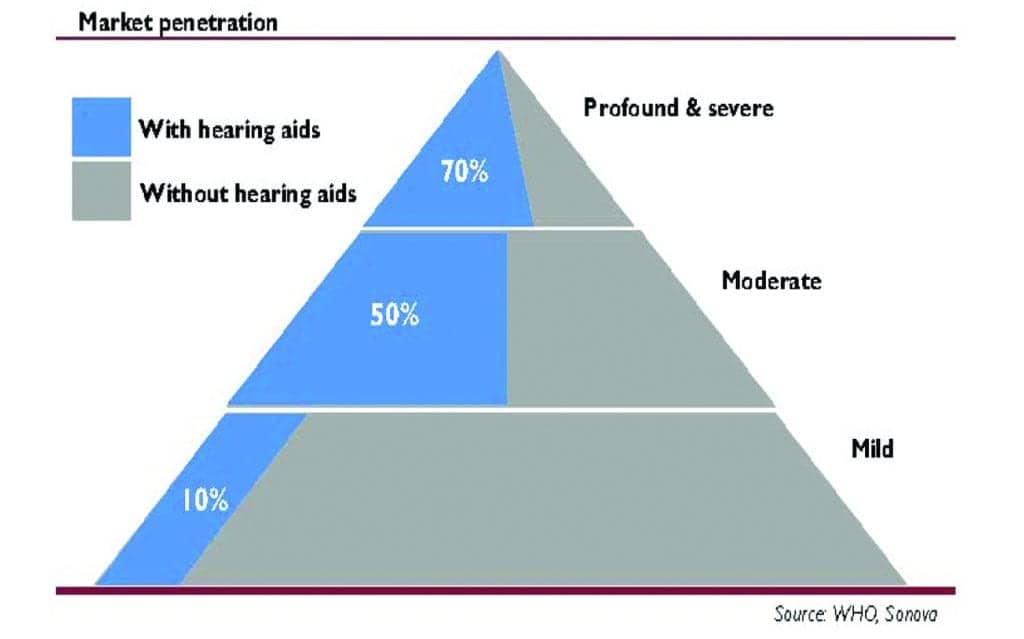

Historically, the hearing industry has been poor at convincing people with milder hearing losses—typically people younger than the average first-time purchase age of 65—to buy a hearing aid. It’s not for lack of trying. By far, the largest portion of the hearing loss population is, indeed, comprised of people with milder losses (Figure 1). So that’s where a lot of money resides. But, in truth, the “younger/mild-loss category” could justifiably be viewed by hearing industry engineers and marketers as a place where good ideas go to die. Counter-intuitively, it is anything but low-hanging fruit. I’ve reported on numerous innovative product launches aimed at people with milder hearing losses that have failed. In my view, hearing aids taking aim at this market segment have traditionally had three strikes against them before getting their “at bat”:

- The aids were generally priced at a sub-economy level, and HCPs would either be leery of it cannibalizing their margins and/or they would mark up the aid and use it as their latest “economy-level” aid—in either case defeating its intended purpose of appealing to younger users with milder hearing losses who are looking for a less-expensive option. It’s also worth noting that return-for-credit (RFC) rates and repair issues for these aids can be at least as high or higher than traditional hearing aids. While most people agree RFC stipulations are a necessary consumer protection, these safeguards do increase manufacturer costs significantly.

- Most milder hearing losses are routinely dismissed even by the best hearing care professionals because they have been taught that dispensing to a patient with mild hearing loss, as indicated by the pure-tone audiogram, is unethical—even given the fact that these patients (and their loved ones) are actively seeking a solution for their perceived (but real-life) hearing problem. Recent articles by Beck et al and Larry Humes demonstrate some of the follies behind defining “normal hearing” using only the audiogram and/or four-frequency puretone averages (PTA4).

- As mentioned above, the compromises in sound quality that milder-loss consumers were forced to accept (combined with the device cost) didn’t justify the better hearing they received in the specific situations they were seeking help for–and too often the benefits did not extend to noisy situations like family gatherings, bars, and restaurants. So, the value proposition just wasn’t there. Also recall Sergei Kochkin’s early MarkeTrak findings that, even if you tried to give away free invisible hearing aids, most consumers wouldn’t accept them if they did not improve speech in noise.

Hearing aid sound quality and innovative speech-in-noise technology—in addition to the hearing industry market dynamics from the impending OTC class of hearing aids (whatever they will look like)—are changing all three of the above factors. If hearing care professionals wish to compete for milder-loss patients (and my opinion is they can and should), they’ll probably need to offer even more economical hearing aids that utilize teleaudiology and pared-down audiology services (eg, from technicians and/or back-office staff) tailored for a younger/working age group who are more comfortable with online services and who place a premium on time and convenience. That means individualizing hearing care, slightly modifying practice strategies, triaging patients, and identifying those milder-loss users who might benefit from these devices and a “blended care model.”

Exceptional sound quality—above cost and all the other “bells and whistles” that the latest generation of hearing aids provide (eg, connectivity, remote fine-tuning, hands-free phone calls, motion-sensors and tap controls, virtual assistants, etc)—may turn out to be THE most important factor in persuading younger people with milder hearing losses to purchase a hearing aid.

Karl Strom is editor of The Hearing Review and has been reporting on hearing healthcare issues for over 25 years.

Karl Strom’s blog Sound Quality as a Tipping Point provides the best succinct explanatin of why people like me with “situational” hearing amplification needs do not use hearing aids — the 24×7 hassle just isn’t worth it for the modest percentage of situations where a hearing aid is really helpful. The issue nod discussed was the “old person” appearance of RIC hearing aids with the unit over/behind the ear. As a young person, I’d much prefer the Phonak Virto Black ITE hearing aid. Much more “with it.” Dr. Strom apparently plans to review the sound quality of the Phonak Paradise. I hope he’ll address the question of whether the Paradise technology will be avaiable in the Virto Black (and if not, why not). My interests are, in descending order, sound quality (and user flexibility), appearance, and — distantly — cost.