PART 1: TOOLS TO IMPROVE ADULT LEARNING

Part 1 of 3: A review of adult learning principles and retention techniques as well as some ideas to improve counseling effectiveness. These techniques demand that we leave our counseling comfort zone and ask patients to do the same.

Talk, talk, talk! Can’t we just fit the hearing aids and send the patient home to learn about them by reading those excellent user manuals that the manufacturer provides?

Well, actually, no. The learning, insights, shared understanding, and strong relationship achieved during a counseling session are essential to both patient and practitioner.

The first in this series of three articles will examine why we should focus on improving counseling skills, and then explores principles of adult learning and tools for retention, suggesting how this information might improve outcomes. Subsequent articles in the series will address issues of social style and questioning techniques as they pertain to counseling success. This series does not presume to be an exhaustive treatise on counseling; however, it will offer some novel approaches.

The articles were motivated by professionals’ enthusiastic reactions to courses on this topic that my colleagues and I have presented over the past several years. Hopefully, they will become a starting point, to be supplemented by further study, with the goals of improving patient outcomes and practice success.

What Is Counseling?

“Counseling is the process of telling people what you found, what it means, and what needs to be done, and doing so with tact and sensitivity.”

|

While at first glance this definition by Jerger1 appears to be a sensitive and thorough definition, it can be revised to make active participation by the patient a larger objective:

“Counseling is the process of giving and receiving information in a way that is meaningful, memorable and usable, changes behavior and facilitates a successful rehabilitative outcome.”2

In the context of providing hearing services, this definition mandates a rather different form of counseling. It requires two-way communication. It demands that the communication be understandable to the patient, not only when it is delivered but also after the patient has left the office. The counseling effort must change behavior; it focuses on outcomes. Talking and listening fall short of the goal if behavior does not change in a meaningful way.

Several years into my tenure as director of a large dispensing audiology clinic, my colleagues and I developed a philosophy of patient care:

It is our responsibility as professionals in communication disorders to demand of ourselves the very best in effective communication. We must overcome the communication disorder in the office to guarantee an effective rehabilitative outcome out in the world.

Overcoming that disorder in the office mandates effective two-way communication. If ever there is a time when we need to go the extra mile to overcome a communication handicap, it is in the process of counseling patients. We cannot allow the handicap itself to get in the way of patients’ thorough understanding of how best to deal with that handicap.

Two types of counseling. The counseling necessary to help a patient use hearing aids successfully is a combination of what Margolis3 calls informational counseling and behavioral change counseling. To achieve a successful outcome, patients must understand the basic workings, plus care and maintenance, of the hearing instruments—which is informational counseling. But they must also change their listening behavior, and often that of their friends and family, in ways consistent with optimizing communication—which is behavioral change counseling. Achieving these two goals requires knowledge of counseling principles and successful execution of the counseling process.

Retention. One of the major deterrents to counseling success is the patient’s failure to remember what they have learned. The problem of retaining information is well documented.3 In medical consultations, patients are likely to retain only 50% of what a physician has told them. Furthermore, only about half of the information they retain is remembered correctly. So we can expect patients to recall correctly about 25% of what we have told them, by no means a sterling outcome.

But don’t think the patient’s limitations are fully responsible for this discouraging outcome. Our skills—the ways in which we counsel—play a major role in retention.

Principles of Adult Learning

Since leaving the clinic and joining the hearing industry, I have spent much of my working time designing and presenting courses to hearing professionals. To optimize the effectiveness of course offerings, I began studying principles of adult learning and realized that they could be applied not only to a classroom situation, but also to a counseling situation.

It is from these studies, guided by the excellent work of Bob Pike4 and his associates, that the following adult learning principles came to be applied to the process of counseling for wearers of hearing instruments. Pike’s Principles of Adult Learning4 are:

1. Adults are babies with big bodies. Babies learn by doing, not just by being told that something is so. At some point in our growing up, teachers and parents stop doing things to teach us and instead just tell us that things are the way they are, or have us read a book as a memorable source of knowledge.

If an adult is given the opportunity to do, to take action on a topic, to play, touch, examine, then learning will improve. We should always be looking for ways to involve the patient actively in the learning process. Don’t just show how to change a battery; insist that they do it. Don’t just insert the aid and describe what you’re doing, require that they do it themselves. Have them clean the aid, put it away for the night in a desiccant container, clean the tube on their BTE. Have them actually carry on a conversation with a spouse in your presence to demonstrate mastery of communication tips.

2. People don’t argue against their own data. If you discover a truth on your own—experience your own personal “Eureka!” moment—you will understand and remember it better than if I describe a truth to you. When you counsel a patient, spend at least as much time listening as you spend talking.

Formal tools like the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement5 (COSI) or other more informal tools to record a patient’s experiences are valuable when it comes time to make a decision about purchasing hearing instruments and prescribing a course of hearing rehabilitation. By using effective, open questioning techniques, you can gather data specific to this patient, and recalling those data in subsequent discussions of recommended interventions enhances the nature of the exchange.

The information a patient has given to you should lead logically to an appropriate intervention. When this approach is used well, a practitioner should never be in the position of persuading a patient to follow a recommendation; the patient’s own data leads him/her to the appropriate conclusions.

Let’s examine one implication of personal data, as related to patient motivation. Some patients just don’t seem motivated to purchase hearing instruments, or once they have them, to follow our instructions on use and care. Pike4 offers three important points:

1) You can’t motivate people.

2) All people are motivated.

3) People do things for their own reasons, not yours.

These little nuggets of wisdom reinforce the need to rely on patient data. Those data represent the personal situations that will motivate a patient to seek resolution of their hearing issues. Frame the instructions and recommendations in terms of what you have learned from the patient, rather than what you know on your own.

3. Learning is directly proportional to the amount of fun you have. Data show that presenting information with humor is likely to increase retention of that information. Obviously, using humor at a time like this, in the midst of what is sometimes an emotionally charged experience, must be done with care and good judgment. However, tapping into shared aspects of our human experience, directly or indirectly, often results in a warm, memorable connection, one that will be remembered better than a lesson presented from a more detached perspective.

In the process of counseling a patient, consider sharing real stories from your own experience. I could tell many stories of patients I have known. One elderly man called me in a panic when he lost his new hearing aid. He came in to have a new impression made, and as I was placing an otoblock, I noticed his missing hearing aid tucked safely in his pant cuff. I might tell about the grandmother who caught her little granddaughter just as she was about to flush Grandma’s hearing aid down the toilet because it was making that nasty whistling noise. Or I might tell about the patient who thought he was about to be mugged in the underground parking ramp after leaving my office, only to realize that he was hearing, not a mugger, but the sound of his own nylon jacket and footsteps.

Little bits of humanity like these will be memorable and will set a positive tone for your interactions. Avoid using jokes as your source of humor, as they seldom create the sort of warm connection that is beneficial to your relationship with a patient.

Multiple Learning Modalities. Along with the importance of requiring action (eg, changed behavior), conveying information in multiple modalities also improves the final outcome. New tools for hearing, seeing and doing are now appearing in the software used to program today’s hearing aids. As one example, Starkey’s Inspire OS software, used to program the new Destiny line of hearing instruments, has several multimodality tools.

SoundView is a fitting tool that shows the real-time output of a hearing aid as if it were being sent into an average ear canal (Figure 1). By monitoring the output of the instrument in real time, it can demonstrate visually to patient and spouse the effect of changing volume control settings or adjusting frequency shaping at the same time the patient hears the changes. This interactive display, combined with the practitioner’s instructions, enhances understanding and appreciation of the hearing aid’s operation.

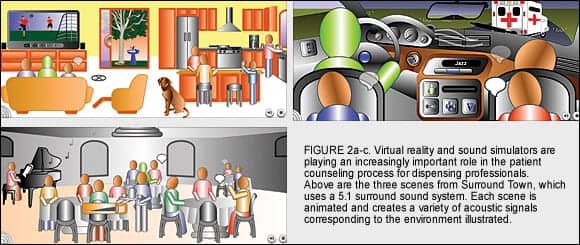

Surround Town is a multimedia fitting tool that creates a virtual reality in the form of a 5.1 surround sound system. Three scenes (Figure 2) represent actual acoustic environments, and within each scene the operator can activate up to 13 animated sound sources, which the patient will hear in realistic acoustic space.

Multimedia fitting tools like this allow the dispensing professional to create situations that the patient can see and hear, then counsel the patient about how to position himself, or what features to select to take best advantage of his new hearing aids. The patient can hear changes in the hearing aids when positioned in different places in each scene, when features are turned on and off, when adaptive algorithms are activated or deactivated, or when different sound sources are turned on and off.

These types of simulation tools can be expected to improve understanding of and confidence in hearing instrument operation.

Tools for Retention

Considering the aforementioned adult learning principles, we might be motivated to find ways to improve the 25% correct retention figure cited above.3 In addition to basic Principles of Adult Learning, Pike4 also offers several practical retention tools that might prove useful in our hearing rehabilitation efforts.

Primacy. We tend to remember well what we learned first. Open your counseling session with a point that is important for the patient to remember.

Recency. We tend to remember well what we learned last. Likewise, end your counseling session with a particularly important point. This is not to say you should fill the middle of your counseling session with trivia. Just keep in mind that you get the greatest impact at the beginning and end, and try to organize information accordingly.

Linking. When presenting a series of points, linking those points together with a memorable word or phrase can improve retention. This principle, at the foundation of the acronym craze, is perhaps best explained with an example.

Patience

Attention

Concentration

Training

Having the patient write the key words will assist in retention more effectively than writing them yourself.

This is only one small example of linking. You might come up with a variety of acronyms appropriate for the counseling session.

“Outstandingness”. Making an outstanding statement at the beginning of a counseling session will get a person’s attention and become a point they will remember. Bold statements can increase confidence and information retention, but they must also be selected judiciously, so as not to sound like a hard sell.

You may want to use a statement that expresses your devotion to the work you are doing or your commitment to achieving good outcomes for your patients. Or you may offer a glowing, yet factual, report of your successes with other patients using the same technology.

Repeat Six Times (6X Rule). If you hear or see new information once, you are likely to retain about 10% of what you learned; if you hear or see it six times, retention increases to 90%. Revisiting new information more than once is vital to retention.

We must be aware that mere repetition may become boring or even annoying. This tool will be most successful if you present the information in a variety of ways, woven into your time spent with the patient. Redundancy without repetition is the goal. Let’s take the task of teaching battery insertion as an example. Below are six ways we can convey the information.

• Show a picture of the battery and battery compartment.

• Tell the patient which way the battery goes into the aid.

• Insert the battery yourself to show them.

• Have the patient insert the battery, and at the same time…

• Tell you how he/she is doing it.

• Instruct the patient to read the user’s guide when they get home, which will cover the point one more time.

While this degree of redundancy may seem extreme, adhering to such a protocol has been shown to improve retention, and when well practiced, can proceed smoothly. The points need not to be presented all in the same session but may be spaced out over an initial fitting and a follow-up a week later.

Windowpaning. Information presented within a visual structure is likely to be retained better than information presented in a list. Let’s take the points we just covered, and place them in a windowpane format.

Using both words and drawings in the windowpanes further enhances retention, as does having the patient do the writing and drawing themselves, rather than your doing it. All of these steps add to the 6X rule, with redundant presentation of points in a variety of modalities.

Start with a blank windowpane form, and have the patient fill it in as you identify the learning points and tell them what to write and draw. (If they’re stuck on a drawing, you might draw a simple graphic that they can copy.) No artistic talent is required; in fact, the art that many of us would produce may become another mechanism for adding humor to the session.

In your office, consider collecting the lists of bulleted points you give to patients about the use and care of hearing aids, along with lists of communication strategies. Now transform those lists into windowpanes, complete with brief verbal descriptions in each pane and a simple graphic to capture their essence.

Acknowledgement

The author is especially grateful to Bob Pike and his colleagues for their instruction and insights into what makes training truly successful.

References

1. Jerger J. Effective Counseling in Audiology. Prentice-Hall;1994.

2. Yanz JL, Pociecha AL. Patient Counseling: Questioning, Retention & Social Style. Presentation at: American Academy of Audiology Annual Convention, Minneapolis; April 7, 2006.

3. Margolis B. Informational Counseling in Health Professions: What Do Patients Remember? Found at: www.audiologyincorporated.com; January 2004.

4. Pike RW. Creative Training Techniques Handbook: Tips, Tactics, and How-To’s for Delivering Effective Training. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: Lakewood Books; 1994.

5. Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8(1): 27-43.

6. Sweetow R. Physical therapy for the ears: Maximizing patient benefit using a listening retraining program. The Hearing Review. 2005;12(10): 56-58. Also available in the www.hearingreview.com archives (Sept 2005).

Correspondence can be addressed to Jerry Yanz, PhD, Starkey Laboratories, 6700 Washington Ave S, Eden Prairie, MN 55344; e-mail: [email protected].

LACE: A New Training Tool

Typically, when we fit patients with their first hearing instruments, we instruct them on how to begin using them in that acoustically complex world out there. We may recommend starting in easy listening situations with only one other talker, then gradually progressing to more challenging situations. These suggestions, however, fall prey to the same limitations of retention as our other pearls of wisdom.

A new training program offers a tangible interactive tool to reinforce such recommendations and provide actual training in listening skills. Listening and Communication Enhancement (LACE)6 is a home-based, computerized, adaptive training program designed to help patients improve their listening and communication skills. The system was conceived by Robert Sweetow and Jennifer Henderson Sabes at the University of California San Francisco and created in collaboration with NeuroTone, Inc.

With regard to adult learning and retention, the very design of the program uses several of the principles we have discussed. It is both auditory and visual. It uses the 6X Rule, using redundancy without repetition. The program finds the level of an individual’s skills, offers examples of tasks from a variety of topic areas, and progresses adaptively toward greater mastery. It requires active involvement—doing—on the part of the patient, and behavioral change is not only the desired outcome, but also an intrinsic part of the training regimen. We expect that LACE will have a significant impact on the amount of learning that takes place in a hearing rehabilitation effort.

LACE is a potentially important tool in maximizing rehabilitative success with hearing instruments. It begins with training in the office and then extends that training into the patient’s home, where listening principles are learned more effectively. Because of its potential benefit, Starkey is making the LACE training program available at no additional charge to patients who purchase Destiny 1200 hearing instruments.