Among image-driven consumers, the appeal of the hearing aid is, perhaps, not unlike the appeal of an Oldsmobile to a Formula 1 driver. Hearing aids can be a tough sell, and the market has not always been kind to the devices, whose uber-competitive manufacturers jockey for the hearts and minds of adults who harbor an increasing expectation of technology and a sometimes-reluctant attitude about the devices themselves.

One industry executive has dubbed them, “A product lots of people need but nobody really wants.”

In the pediatric amplification market, however, hearing instruments take a central role in the development of human communication, which relegates grown-up worries about style and perception to the back seat. Making a purchase decision that will affect a child’s personal development for a lifetime also means sorting carefully through the smorgasbord of available technology that must satisfy parent, patient, and clinician.

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

|

| Christine Gilmore Eubanks, PhD |

A successful fitting with one of today’s advanced aids specifically designed for pediatric use demands an entirely different mindset than that needed for fitting adults, says Christine Gilmore Eubanks, PhD, program director, audiology services at John Tracy Clinic in Los Angeles.

“With children, it’s all about audibility,” says Eubanks, who in 2007 helped launch the Baby Soundcheck Infant-Toddler Screening program in East Los Angeles, designed to help monitor the hearing health of infants and children outside the hospital environment.

“Kids need to hear everything around them and need to be able to overhear conversation for incidental learning,” Eubanks says. “So when teachers complain that the child isn’t responding to speech sounds, and the educational audiologist says the aids aren’t meeting audibility targets, the response shouldn’t be ‘Won’t that be too loud?’ or ‘That will sound tinny.’

“That’s where research comes in,” Eubanks says.

SUCCESS AND THE BIG PICTURE

Today’s advanced pediatric amplification devices must be backed up by guidance and educational resources that support parents, teachers, clinicians, and children connected with the use of the devices, says Tom Powers, PhD, vice president for audiology and professional relations at Siemens, Piscataway, NJ.

“Any companies that choose to be in the market realize they have to provide a good system of support to these devices in order to be successful,” Powers says.

Powers says he believes pediatric amplification solutions must be approached with a double focus that accounts for the needs of the dominant adult market while maintaining the performance and lifestyle demands of the pediatric market. As device technologies are conceived and pushed along development paths, Powers suggests they should always be viewed through the lens of all the stakeholders of a pediatric fitting.

“Where I think companies probably fail,” Powers says, “is they design it, finish it, and then go back and say, ‘OK, what are we going to do to this so it will work for kids.’

|

| Tom Powers, PhD |

“At that point, it’s too late,” Powers adds.

Powers says he has observed manufacturers entering the pediatric amplification market armed with a well-designed hearing instrument only to realize the ancillary support that tethers the device to its community of users, educators, and clinicians lies well beyond the scope for which they had prepared.

“All the support that has to come around that child is certainly as important as the technology of the hearing instrument,” he says. “Without it, really good technology might not be enough.”

THE COMPLETE PICTURE

Oticon Inc, Somerset, NJ, is one manufacturer that has fielded a pediatric amplification program built on multiple layers of support, a framework that appears to follow a blueprint strikingly similar to the one described by Powers.

All of Oticon’s products are deployed with marketing materials customized for the pediatric market, according to Sheena D. Oliver, AuD, MBA, manager of pediatrics at Oticon.

“We have introduced a workbook to assist parents in becoming active and informed members of their child’s support team as well as being a resource for teens that offers advice on structuring the school environment and creating opportunities for social interaction that build responsibility, self-advocacy, and self-esteem,” Oliver says.

“In addition to our award-winning OtiKids Web site, we’ve also unveiled a counseling CD designed to make parent counseling easier and more effective,” Oliver adds.

Powers points out that Phonak also has created a buffet of materials that support its pediatric hearing instruments

“Phonak leads the pediatric market in terms of unit sales, but they’ve been mindful to develop all the support items, too,” says Powers, a 25-year veteran employee of Phonak’s competitor, Siemens. “Whether it’s a printed piece or phone support, you have to train people who have the resources and can get answers very quickly to the pediatric audiologist to support the products.”

DIGITAL GEAR FOR DEVELOPING EARS

On today’s stage of pediatric hearing instruments, there is a wash of digital technology and component miniaturization that seems to signal the arrival of a high water mark in the devices’ state of function.

At Widex USA, Long Island City, NY, particular attention has been paid to designing signal processing features that address the special needs of the pediatric population. Jane Auriemmo, AuD, Widex’s Pediatric Partnership Program Manager, says integrated signal processing puts into service several of the features found in the company’s Inteo hearing aid.

The audibility extender is a linear frequency transposition feature designed to enable children with precipitous sensorineural hearing loss to have access to high-frequency speech information, which, Auriemmo says, have been reported by both clinicians and parents to improve high-frequency phoneme production when the extender is used for as little as 6 weeks.

Inteo also features a 15-channel directional system that allows the microphone polar pattern in a particular channel to automatically shift to omnidirectional whenever speech is dominant in that channel.

“Similarly,” Auriemmo says, “the speech enhancer feature incorporates the hearing loss of the child in determining the type and amount of gain changes in noisy environments.

“The goal,” Auriemmo emphasizes, “is to preserve speech cues in noisy environments.

|

| Oticon Amigo |

Powers explains that Siemens’ Ear-to-Ear technology has provided the latest boon to the company’s pediatric amplification set. “For children and young adults, if they move into an area that’s noisy, not only does the hearing aid sense it, but even if the noise is louder on one side, the hearing aids communicate and both of them go into the directional mode, instead of just one.

“We’ve had our greatest success in pediatrics with our Centra line, which is mainly because it has a lot of things that the child may not need when they’re quite young, but can use later on as they mature,” Powers adds.

Tapping the wish list of pediatric hearing care professionals helped Oticon engineers craft their Amigo product line of hearing instruments, according to Oliver. “They asked for an FM system that is durable, user-friendly for children, and easy to program and does not require lots of setup time and cumbersome cords and cables and computers,” she says.

Oliver lauds datalogging as, perhaps, the technology that has most benefited pediatric consumers in recent years.

“It provides a sense of surety,” Oliver says, “from school to playground and at home.”

THE NEED FOR SPEED

Loaner programs assure that pediatric amplification needs of children are met while the sometimes sticky issues of compensation for hearing instruments are sorted through while families wait out the lengthy lead times of new instrument orders.

The Siemens loaner program, Powers says, is simply an extension of the support the company provides for its pediatrics program as a whole, which the company makes available to centers that handle large volumes of pediatrics.

Auriemmo, speaking for Widex, characterizes the company’s loaner program as one that enables pediatric clinicians to fit children earlier with an advanced level of technology.

“The industry wins not only by contributing to better outcomes,” Auriemmo says, “but also by exposing more clinicians to their hearing aids, fitting software, and technical support.”

Oticon’s loaner program, Oliver says, was the company’s response to the disruption that can occur in speech and language development when delays occur in acquiring a hearing instrument for a child.

“We find that in the majority of instances, the benefits children and families experience from our advanced technology hearing solutions during the 3-month loan period are enough to motivate purchase,” Oliver says.

WHEN MORE CAN BE LESS

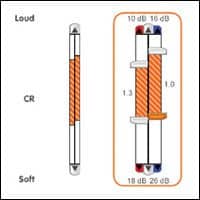

Eubanks says the advanced bells and whistles built into the latest amplification solutions should be carefully considered in cases of pediatric fittings.

“For example, directional microphones are terrific for listeners who are looking at the speaker,” Eubanks says, “but how often do you see a 2-year-old looking toward the speaker—a parent or teacher? We routinely set mics to ‘omni’ for kids younger than school age.”

Noise reduction circuitry that involves reduction of low-frequency sounds, Eubanks says, might be detrimental to detection of low-frequency speech cues, which are important for prosody and intonation, as well as formant information, voicing, and nasality. Multiple memories, Eubanks adds, while a benefit for individuals with fluctuating losses, “probably wouldn’t otherwise be used with children.”

What Eubanks says she would most like to see emerge in the wake of hearing aid technology’s advance is an effort made toward a truly water-resistant instrument with good sound quality.

“There have been a couple of attempts,” Eubanks says, “but their poor sound relegated them to being spare aids to wear at the beach. What we need are aids that can stand up to sweaty kids!

“If cochlear implant companies can do it,” Eubanks says, pondering the challenge, “the hearing aid industry should be able to.”

Frank Long is associate editor for Hearing Products Report. He can be reached at [email protected].