A major healthcare trend is that “patients” increasingly behave more like “consumers” who have a choice in their healthcare options. The new generation of consumers of healthcare—including hearing care—are open to new ways of engaging with providers, including telehealth. Although providers have greater concerns in this area, advances in technology point inescapably toward incorporating aspects of telehealth in hearing healthcare. The article considers how the trend toward consumerism in hearing healthcare might interact with other trends, including telehealth.

Technology | April 2017 Hearing Review

Part 1: Telepractice tools enhance, not replace, empathetic professional care

During the past decade, one megatrend that has emerged in healthcare is the empowerment of the end-user. In fact, “patients” have increasingly behaved more like “consumers” who have a choice in their healthcare options. Concerning hearing healthcare, this trend towards “consumerism” has aligned almost perfectly with the transition to the “Baby Boom” era consumer, creating previously unseen opportunities and challenges for the industry.

On one hand, this new generation of hearing aid user has expanded the market, lowering the average age of first-time hearing aid users (to 63.3 years of age) and increasing market penetration (to 30%) relative to previous years.1 On the other hand, the Boomers are forcing changes to “business as usual” by insisting that hearing aid service and delivery focus on convenience, end-user control, and cost savings.

In short, today’s first-time hearing aid user in most global markets is younger, employed, and focused more on the accuracy and efficiency of care than their predecessors. The risk of consumerism is that expedience could sacrifice quality of outcome or practitioner/end-user engagement.

This article is the first of two in which we will consider how the trend toward consumerism in hearing healthcare might interact with other trends, such as telehealth. Specifically, how might these emerging trends be used to empower end-users while preserving the role of the professional in the hearing aid fitting process?

Current status of the hearing aid fitting process

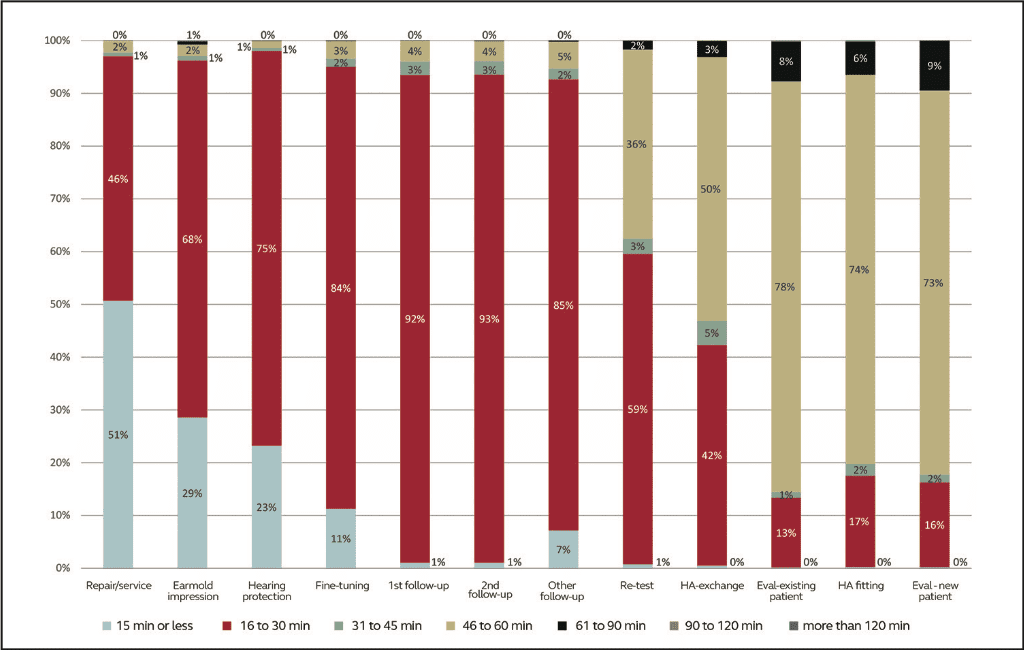

In his review of current hearing aid fitting trends, Kochkin2 reported that, on average, approximately four office visits were required to successfully fit individuals with hearing aids in the US. The average number declined by 1.2 visits when fitting verification and validation measures were used (Figure 1). This is consistent with information from the database of a large hearing aid dispensing practice spanning 10 years and including 85,000 clients (no personal information was made available to ReSound). In this practice, verification and validation are standardized as part of the fitting protocol, and the average number of visits associated with each hearing aid purchase per client was 3.5 including the initial fitting. Notably, service-related visits accounted for approximately half of all office visits, with visits for fine-tuning taking a full 28% share of the total. Although fine-tuning appointments comprised the greatest number of visits, they were also among the shortest, along with appointments for repair/service, earmold impressions, and initial follow-ups. Of all the appointments for fine-tuning, 96% of them took 30 minutes or less. The distribution for different appointment types is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. [Click on figures to enlarge.] Average patient visits to fit hearing aids based on use of verification (real-ear measurements) and validation (subjective or objective) procedures. From Kochkin.2

Figure 2. Distribution of time spent per appointment type in a large hearing aid dispensing practice. The data set includes almost 52,000 appointments.

The data set includes almost 52,000 appointments.

Finally, users need to try out fine-tuned adjustments in their everyday environments that are difficult to replicate in clinical settings. Taken together, this information suggests that at least some fine-tuning appointments are inefficient—and perhaps even unsatisfactory—for both HHPs and users.

Many new and experienced hearing aid users prefer to utilize the expertise of their HHP to optimize hearing aid outcomes. More recently, the introduction of “Made for iPhone” (MFi) hearing aids has given users the ability to easily fine-tune some aspects of their hearing aids in “real world” settings on their own. The willingness among hearing aid users to assist with the adjustment of own device is supported by recent data. Among a total of 635 hearing aid users from the USA, Germany, and Japan, the vast majority indicated that they would like to have “more involvement and control” in adjusting their hearing aids (unpublished data; ReSound market survey research conducted by a third-party agency).

At issue is whether “more involvement and control” means “do-it-yourself.” Laboratory studies of self-fitting hearing aids show that even rudimentary self-fitting systems that allow the user to customize but a few parameters (e.g. bass, midrange, treble, overall volume) can provide results comparable—and sometimes preferable—to fitting by a professional.4-8

However, the involvement and support of the HHP remains significant to overall satisfaction, as well as confidence in results. A recent interview-based study asked about the perceptions of internet-based hearing instrument acquisition and self-fitting among 18 experienced hearing instrument users.9 The study participants saw some advantages to this kind of direct access to product, including the convenience of not needing to leave home to acquire devices. However, they were concerned about a lack of personal contact with a HHP and how their individual hearing losses would be factored into programming and adjustments. Even though there was greater convenience perceived, participants in the study expressed a preference to be treated by a knowledgeable, experienced expert.

The evolving trend of telehealth may provide HHPs and users with a means to enhance efficiency and satisfaction during the hearing aid fitting process without compromising the value of face-to-face interaction.

The Emerging Role of Teleaudiology Relative to Personal Consultation

Krupinski10 described telehealth (i.e. teleaudiology) as the use of telecommunication technologies to reach out to patients, reduce barriers to optimal care in underserved areas, improve user satisfaction and accessibility to specialists, decrease professional isolation in rural areas, help medical practitioners expand their practice reach, and save patients from having to travel or be transported to receive high quality care. An obvious advantage of teleaudiology is that it may help overcome common barriers to getting hearing aids, such as cost and distance from service providers.11

One of the concerns around the concept of teleaudiology is the ability of users to provide precise descriptions of issues they may have experienced in “real world” environments. However, a majority of common hearing aid related complaints can be mapped to solutions in a relatively straightforward manner. Jenstad et al3 demonstrated that a vocabulary of 40 frequently reported terms in the description of specific hearing aid fitting problems was sufficient to develop an expert system for hearing aid adjustments in response to a complaint from a hearing aid user.

Other concerns related to teleaudiology are overuse of care (e.g. unnecessary consultations), underuse of care (e.g. failure to referral for a necessary consultation), and poor technical or interpersonal performance (e.g. incorrect interpretation or inattention to hearing aid user concerns). However, data suggest that teleaudiology and conventional face-to-face audiology care around hearing aid services are comparable in terms of these concerns.12 Research from Blamey et al13 and Pross et al12 also provide evidence of the effectiveness of different teleaudiologic methods in the approach of hearing aid fitting. Finally, personal consultation and teleaudiology are both highly effective based on results using the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA).12

Taken together, the available evidence suggests that a practice that can leverage the specific advantages of personal consultation and teleaudiology has potential for wide adoption among hearing aid users, improved access to hearing aids, and preserved or even increased high satisfaction. But how do users and HHPs view this concept?

The User’s Perspective

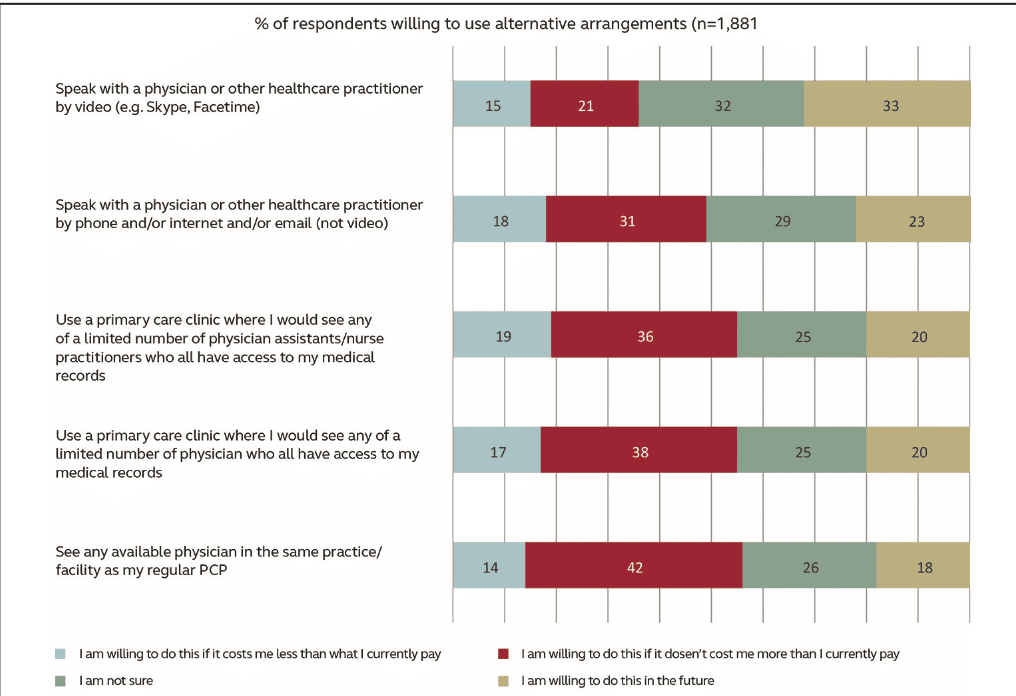

As discussed, current and emerging hearing aid users prefer to have the professional support of the HHP instead of “do-it-yourself.” At the same time, they are open to alternative ways to satisfy that preference, especially if it saves time and money. In a 2016 survey of more than 1,000 US adults over the age of 55 years (ReSound market survey research conducted by third-party agency), nearly one-half of hearing aid users reported that they had to drive 21 minutes or longer to reach their HHP, and 37% expressed interest in using telemedicine (telepresence) as an option to save time. This is consistent with data regarding willingness of respondents to use alternative arrangements to face-to-face healthcare if it saves time or money14 (Figure 3).

Of those with self-described hearing loss, 86% of respondents in this market survey saw value in incorporating telehealth into a healthcare regimen. Of interest was that 51% of respondents did not believe that their level of hearing loss merited a visit to a professional (25% were actually wearing hearing aids); 1 in 10 attributed their reluctance either to time constraints or distance to travel to the HHP as a primary barrier. Overall, 37% of all respondents indicated that they would be strongly interested in a telehealth service as part of their hearing healthcare treatment, and the vast majority had access to a computer (73%), smartphone (65%), or tablet (50%) in their home.

Cordina et al14 also reported that acceptance of use of a technology device (e.g. smartphone, tablet) for communicating health-related activities is increasing in all age brackets (Figure 4). Clearly, there is emerging interest among potential and current hearing aid users

to incorporate a telehealth service as part of their treatment. Furthermore, in the past, “telehealth” was an imposing proposition for many older individuals, as it often involved specialized equipment that was often complicated to use. Today, cell phones are ubiquitous, and a smartphone is the only “technology” needed by the consumer for teleaudiology with MFi hearing aids.

The HHP’s Perspective

Bashshur et al15 reviewed more than 2,000 articles on the empirical evidence of telemedicine interventions in primary care. While their review indicated a wide variance in adoption and use, it also revealed a difference in acceptability between patients and providers, with patients being more open to such practices than providers are.

A survey among hearing healthcare providers16 also revealed some skepticism of teleaudiology. The majority of respondents indicated that teleaudiology is likely to have a minimal effect on the quality of hearing healthcare in audiology and the quality of client-practitioner interactions, although many respondents indicated that teleaudiology would have a positive effect on accessibility to service. A small minority of respondents indicated that teleaudiology would have a negative impact on quality of care in audiology. In addition, HHPs cite privacy concerns, cost (lack of reimbursement), and workload concerns as barriers to embracing teleaudiology.17

A concern related to workload that is often voiced by HHPs is the potential for disruption to clinical practice that could occur if they must be available “24/7.” However, the expectation that telehealth necessarily leads to overuse of services has not been proven.12 In addition, there is a common misconception that telehealth models are necessarily synchronous. In other words, HHPs may believe that both the HHP and consumer must be available and present in real time to take advantage of teleaudiology. This is not the case. HHPs may be surprised to learn of the advantages presented by new technologies that foster the relationship with the consumer without requiring both to be present in real time.

The rapid advance of technologies such as smartphones and tablets along with apps, cloud storage, and informatics point to an evolving business model that can meet the expectations of consumers while adding efficiencies for providers. Alternatives to synchronous models provide greater flexibility for continued connection between both parties while making it more convenient for both the clinician and the user, with fewer physical visits required by greater engagement through “virtual” contact between the two parties.

The Value of the HHP/Consumer Connection

HHPs naturally focus greatly on the benefit provided by amplification. Are users hearing better? Are they functioning better in their everyday lives? It seems logical that a user who benefits from their hearing aids will also be satisfied with them, but all HHPs know this is not the case. Satisfaction is more complex and involves a multitude of factors that also include benefit.

Interestingly, users may not even be fully aware of what influences their satisfaction most. This appears to hold true for other healthcare areas as well. Cordina et al14 reported that the a priori stated importance of certain aspects of hospital stays were poorly correlated with overall inpatient satisfaction scores for hospitals. For example, approximately 70% of 1,160 respondents rated “parking/easy access” as “important” or “very important.” Thus, one might think that parking and easy access would correlate strongly with overall satisfaction. In fact, the correlation was less than 50%. This may reflect a tendency on the part of the consumer to overstate the influence of concrete, tangible factors on their overall experience. The factors that correlated most strongly, however, had to do with empathy of the providers and the information provided about treatment. In other words, connection to the provider and engagement were highly influential in determining overall satisfaction.

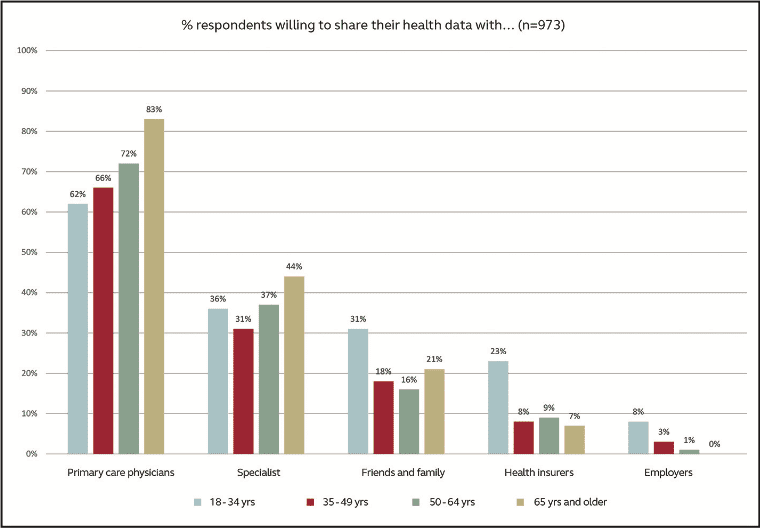

Figure 5. Distribution of respondents who are willing to share health data with different parties.14

The extrapolation to hearing healthcare is to highlight the importance of the role of the HHP, and is in agreement with the finding that the service provided in connection with a hearing aid purchase is crucial in determining satisfaction, as shown by the research of Cox and Alexander.18 While the technology serves as the tool, engagement of the consumer and connection to the HHP is vital to successful outcomes.

The bottom line is that both the tools for teleaudiology and the relationship with the HHP are vital to the success or failure of the program. The HHP is the most trusted source of information in the process, and patients of all ages are suspicious of data storage with anyone other than the HHP or the Primary Care Provider (Figures 5 and 6). Teleaudiology tools do not replace the HHP, and, indeed have the potential to enhance the HHP and consumer relationship.

Summary

Figure 6. Distribution of respondents who are willing to share health data with different parties.14

Consumerism in hearing healthcare means that hearing aid users want to be more engaged and have more control in the hearing aid fitting process. At the same time, the expertise of the HHP continues to be greatly valued. Emerging teleaudiology solutions provide potential opportunities for preserving or even enhancing the continued connection between HHPs and users by improving clinical efficiencies, user satisfaction, and successful outcomes.

The most effective solutions will take into consideration the balance between providing immediate, improved access for users while also ensuring HHP engagement and control of the process, data security, and improved outcomes through continued contact. Part 2 of this article will discuss specific solutions that leverage teleaudiology in a way that strikes this balance.

References

-

Abrams HA, Kihm J. An Introduction to MarkeTrak IX: A New Baseline for the Hearing Aid Market. Hearing Review. 2015;22(6):16.

-

Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: Reducing patient visits through verification and validation. Hearing Review. 2011;18(6):10-12.

-

Jenstad LM, Van Tasell DJ, Ewert C. Hearing aid troubleshooting based on patients’ descriptions. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003; 14:347-360.

-

Elberling C, Vejby Hansen K. Hearing instruments: Interaction with user preference. In Rasmussen AN, Osterhammel PA, Andersen T, Poulsen T, eds. Auditory Models and Non-Linear Hearing Instruments, Proc 18th Danavox Symposium. Denmark: Holmen Center Tryk;341-347.

-

Moore BC, Marriage J, Alcantara J, Glasberg BR. Comparison of two adaptive procedures for fitting a multi-channel compression hearing aid. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(6):345-357.

-

Dreschler WA, Keidser G, Convery E, Dillon H. Client-based adjustments of hearing aid gain: The effect of different control configurations. Ear Hear. 2008;29(2):214-227.

-

Zakis JA, Dillon H, McDermott HJ. The design and evaluation of a hearing aid with trainable amplification parameters. Ear Hear. 2007;28(6):812-830.

-

Keidser G, Convery E. Preliminary observations of self-fitted hearing aid outcomes. Hear Jour. 2016; 69(11):34-38.

-

Chandra N, Searchfield GD. Perceptions toward internet-based delivery of hearing aids among older hearing-impaired adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016;27:441-457.

-

Krupinski EA. Innovations and possibilities in connected health. J Am Acad Audiol. 2015;26:761-767.

-

Schweitzer C, Mortz M, Vaughan N. Perhaps not be prescription–but by perception. In Strom KE, Kochkin S, eds. High Performance Hearing Solutions, Vol 3: Hearing in Noise. Hearing Review. 1999;6(1)[Supp]:59-62.

-

Pross SE, Bourne AL, Cheung SW. TeleAudiology in the Veterans Health Administration. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(7):847-850.

-

Blamey PJ, Blamey JK, Saunders E. Effectiveness of a teleaudiology approach to hearing aid fitting. J Telemed Telecare. 2015;21:474-478.

-

Cordina J, Kumar R, Moss C. Debunking Common Myths about Healthcare Consumerism. McKinsey & Company report. 2015. Available from: http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/debunking-common-myths-about-healthcare-consumerism.

-

Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine intervention in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22:342-75.

-

Singh G, Pichora-Fukker MK, Malkowski M, Boeretzki M, Launer S. A survey of the attitudes of practitioners toward teleaudiology. Int J Audiol. 2014;53:850-860.

-

Atherton H, Sawmynaden P, Sheikh A, Majeed A, Car J. Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012; [Nov]14;11:CD007978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007978.pub2.

-

Cox T, Alexander G. Measuring satisfaction with amplification in daily life: The SADL scale. Ear Hear. 1999;20(4):306-20.

Original citation for this article: Fabry D, Groth J. Teleaudiology: Friend or foe in the consumerism of hearing healthcare? Hearing Review. 2017;24(4):16-19.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or Jennifer Groth at: [email protected]