Final Word | September 2018 Hearing Review

My wife and professional colleague, Alison Grimes, and I were planning to meet for dinner one recent evening. At the end of the work day, she heads east from UCLA toward Orange County and I head north from the southern part of the county. We were looking to calibrate our driving so we arrived at the restaurant at roughly the same time. I knew that in addition to her management responsibilities that day, she also had a patient scheduled to be fit with new hearing aids. Using terminology often used in some busy hearing aid-oriented practices, I asked “What time is your hearing aid delivery scheduled?” She responded that UPS had delivered the hearing aids a couple of days prior. The fitting was to be at 2:30 PM on the day in question.

She has a point. What we do is much more than delivering; it is in the fitting where a device is mechanically and acoustically fit to achieve the outcomes sought in the treatment plan. The terms “delivery” and “fitting” may be synonymous to our ears but represent different processes. I doubt that many patients would appreciate the difference, but in internal intra-professional language we may be sending an improper message to each other as clinicians.

Bob DiSogra recently posted on a professional forum his disdain for “factory repair” or “factory trained representative” as common descriptions. His point is that hearing aids are made by manufacturers, and the support personnel we see are typically audiologists or experienced manufacturer representatives who bring professional expertise to the table. He also prefers to note that repairs are completed at a lab, not at a factory. The differences may be subtle but may make a difference in the way that a patient perceives our products and services.

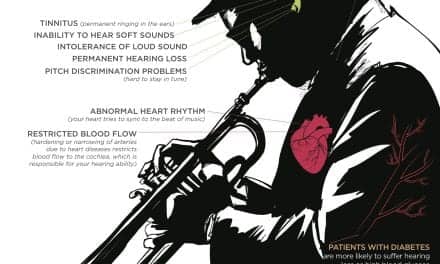

Describing test results to patients can be interesting. If someone has gone to the trouble to make an appointment and seat themselves in our office, they may have difficulty hearing or understanding. We may call this a hearing loss. There are some who disagree, pointing out that the person in question may never have had the ability to hear and hasn’t “lost” anything, they are simply different.

Likewise, when it comes to degree of loss, “mild” or “moderate” may have meaning to us, but may not communicate the issue very well to the patient and others. I like to use a description that anchors the hearing loss to typical sounds that we encounter. I may say: “You have hearing that allows you to detect soft conversational speech, but you may not hear enough of it to fully understand the message.” If an ear is unaidable, or has no response, I do the same with words, avoiding phrases like “dead ear” or “single-sided deafness.” I cringe at the single-sided deafness description for a couple of reasons. It was coined by a marketing team and is often inaccurate. I think we should use words that tell the full story rather than jargon.

“Realistic expectations” is a description that we use among ourselves about acceptance of hearing aids and what may be possible for a given patient. I think it is a perfectly good term to use for discussion among ourselves, but probably doesn’t belong in patient-facing discussions. It can work in written educational materials, but may be misconstrued in a discussion about a patient’s progress with a hearing aid fitting. I think that I’d be insulted if I interpreted something a physician told me in a way that suggested that she thought I wasn’t being realistic.

The Final Word? So much of what we do as we face patients is counseling and teaching about hearing loss and options for treatment plans. Our message can go missing if we do not use terminology that clearly describes the situation and creates a narrative that matches the patient’s ability to receive and comprehend it.

Citation for this article: Van Vliet D. Words matter to our patients and colleagues. Hearing Review. 2018;25(9):50.

Image: © Diana Eller | Dreamstime.com