While auditory training may improve performance, the amount of improvement will be limited to the (un)availability of audible cues.

It has been almost 5 years since Widex reintroduced frequency transposition as an approach to regain audibility of the high frequencies that are either unaidable or unreachable. Since the introduction of the Audibility Extender (AE),1 we have conducted several studies using adults and children as subjects to demonstrate its efficacy.2-5 In general, we have demonstrated that the use of AE with optimally selected settings, when paired with proper training and use of the device, yielded positive changes in the wearer’s identification of speech sounds, especially of voiceless and fricative sounds. Such benefits were seen in both quiet and noise conditions.5

Results of our reported studies showed that significant improvements in consonant identification scores occurred after the subjects have worn the AE for 1-2 months. Speech identification scores with the AE during the initial fit, although improved, were not statistically different from the scores measured with the non-AE program.

Because the speech perception benefits we reported were typically seen along with extended AE use paired with auditory training, some may question if the noted improvement with frequency transposition is a result of training or experience alone. This casts doubts on the efficacy of frequency transposition in that the newly available cues from transposition may not provide any value to the wearers.

This paper will shed additional evidence on the efficacy of the AE and the importance of training.

What Does Auditory Training Provide?

Training provides generalized overall improvement. It is generally acknowledged that training facilitates learning. Indeed, several recent studies suggest that providing training to hearing aid wearers improves their auditory skills in the specific trained areas.6 In addition, training improves hearing aid satisfaction and reduces hearing aid returns.7,8 Training sharpens the wearer’s auditory processing skills and increases their awareness of sounds. This can result in a general improvement in speech perception. Thus, it is not unreasonable to question if training alone could have led to the improvement in the speech perception benefits seen with the AE algorithm.

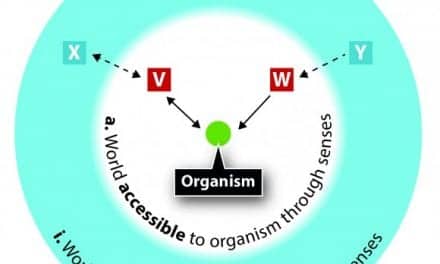

Training provides specific opportunity to use/realize newfound cues. On the other hand, it is also reasonable to expect that, if high frequency cues were not available (because of the severity of the hearing loss or limitations of the hearing aid), the improvement in speech perception with training can only be limited. After all, the identification of speech sounds is contingent on the availability of specific acoustic cues. The absence of the acoustic cues would provide no basis for the auditory system to identify the target sounds.

An example may be seen in children with a precipitous high frequency hearing loss who undergo speech therapy without wearing proper amplification. Despite every good intention and effort on the part of the speech pathologists or auditory verbal therapists, the children’s production of the high frequency sounds does not improve.

In practice, the ultimate consequence of training is that it provides an opportunity for the trainees to focus their attention on whatever cues they have available so they can be utilized more effectively. This means training is important; however, just as important is the availability of usable cues.

This also means that the outcomes of training with frequency transposition will likely lead to greater improvement than training without frequency transposition. The data we have collected support this hypothesis.

Evidence to Support Training AND the Right Program

Evidence in a pediatric study. In one of our reported studies, Auriemmo et al2 included training with the non-AE program at the beginning of their study to obtain a baseline on the potential impact of training on nonsense syllable identification. In addition, the authors wanted to ensure that any potential improvements that might be seen with the AE program in subsequent trials was not simply the results of training, but training with the transposed high frequency cues from the use of the AE.

In the study, Auriemmo et al evaluated 10 children ages 6 years to 13 years 6 months from the Special School district in St Louis. These children had hearing thresholds that ranged from normal to moderate in the low frequencies and from severe to profound in the high frequencies. The average language age of the children was within 2.2 years of their chronological age.

The children’s phoneme recognition on a nonsense syllable test was measured at 30 dBHL and 50 dBHL input levels. The performance was compared among three conditions:

- With the children’s own hearing aids;

- With the Widex Inteo hearing aid utilizing the AE; and

- With the same instrument without the AE (ie, master program).

|

| FIGURE 1. Consonant identification scores as a function of different hearing aid conditions over time at the 30 dBHL (about 50 dBSPL) test condition. |

During the initial visit, the children were tested with their own hearing aids and also on the Inteo hearing aid in the master program (ie, no AE). The children wore the Inteo hearing aids home for 3 weeks in the master program. During that time, auditory training was provided by an auditory verbal therapist on a weekly basis in a small group (2 persons). Testing on the master program was repeated when the children returned in 3 weeks. During the same session (or immediately afterwards), the children’s performance was evaluated with the AE program. The children then went home with the AE program for 3 weeks. Again, the same auditory verbal therapist worked with the children during that time, and they were then evaluated on the AE program. The children went home with the AE program and received another 3 weeks of training with the AE program. Their consonant identification scores at the 30 dBHL (or roughly 50 dBSPL) condition over time are shown in Figure 1.

There was a substantial improvement in phoneme scores between the children’s own hearing aids and the study hearing aids even in the master program and without experience. Almost 30% improvement was immediately recognized. This was likely the availability of extra audibility cues provided by the Inteo hearing aids.

On the other hand, if one compares the scores between the master program measured at baseline and at the 3 weeks post-baseline (after auditory training with the non-AE program), one is not able to find any improvement in NST score even though the children were trained. NST scores measured with the AE program gradually increased over time to about 7% improvement at 3 weeks post-fitting to almost 20% at 6 weeks post-fitting. In other words, training with the non-AE program did not help, while training with the AE program improved scores over time.

This suggests that training without the additional high frequency cues could not improve the children’s syllable identification scores beyond what the master program can provide at baseline. On the other hand, the additional high frequency cues provided by the AE program were not immediately usable (ie, performance at AE baseline was similar to that of the master program) until the children were trained on the use of such cues.

For the AE to be effective, both the extra high frequency cues and the training activities are important to effect positive changes.

|

| FIGURE 2. Consonant identification scores for the non-AE (master) and AE program over time at the 50 dBSPL, 68 dBSPL (quiet), and 68 dBSPL (in noise at +5 SNR) test conditions (n=8). |

Evidence in adult study. Kuk et al5 evaluated consonant identification scores on 8 adults with a severe-to-profound high frequency hearing loss using the Widex nonsense syllable test, ORCA-NST,9 in quiet (50 dBSPL and 68 dBSPL) and in noise (68 dBSPL, +5 dBSNR). Subjects were fit with the Widex mind 440 m-model (m4-m) behind-the-ear hearing aids binaurally in the AE mode, and their speech scores with both the master program and the AE program were measured initially. They wore the AE program home for 1 month and were instructed to complete a self-paced “bottom-up” training regimen10 while wearing the AE program. They returned after 1 month, and their performance on the ORCA-NST was measured. They wore the AE program home for another month but were not instructed to complete any special auditory training. Their performance on the ORCA-NST was again measured at the end of the 2-months trial. Subjects returned to their own hearing aids at the completion of the study.

For all the test conditions (50 dBSPL in quiet, 68 dBSPL in quiet, and 68 dBSPL in noise), a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05 level) was reached between the AE condition measured at the 2-months post-fitting interval and the master program and the AE program at the initial fitting. The difference between the AE and the no-AE conditions at the 50 dBSPL presentation level was also significant between the initial and 1-month intervals.

The data showed that the AE program was statistically similar to the master program at the initial fit. However, the performance on the AE program improved over time to result in the significant difference between AE and master programs at the 2-months visit. It should be noted that the AE program was the only program that the subjects were being trained on and that they wore in their daily lives. This supports the assertion that the training/using of the AE program improves consonant identification.

But Can the Improvement Simply Be the Result of Training Alone?

The Kuk et al5 report was only the first part of this study. About 4 to 6 months after the reported period, we invited all 8 subjects to return for a follow-up study. At that point, any experience with the AE program would have been “washed out” from the discontinued use of the study hearing aids. Although we tried to contact all 8 subjects, only 5 were able to return. Consequently, the data from the follow-up study was based only on these subjects. Their average audiogram was similar to that of the larger group of 8 subjects.

|

| FIGURE 3. Consonant identification scores measured with the master (non-AE) program at the time of fitting, after 1 month of training, and after an additional month of wear without formal training (2 months) under different test conditions (n=5). |

|

| FIGURE 4. Consonant identification scores measured with the master (non-AE program (left) and AE program (right) at the time of fitting, after 1 month of training with the master program, and after an additional month of wear of the master program without formal training (2 months) under different test conditions. The subjects wore the master (non-AE) program during the course of the study (n=5). |

|

| FIGURE 5. Relative changes in consonant scores measured with the AE program over the initial AE consonant scores measured at the time of fitting. In the first study, subjects wore the AE program home. In the second study, subjects wore the master (non-AE) program home. V2-V1 shows the change in score between the second visit (1 month training) over the initial fitting visit. V3-V1 shows the change in score between the third visit (1 month training and another month of use, or 2 months) over the initial fitting visit. |

Subjects followed the same protocol and schedule as in the Kuk et al5 study. The major difference was that only the master (non-AE) program was used. They were fit with the Widex m4-m BTE hearing aids binaurally in the master program mode and their phoneme scores on the ORCA-NST were measured initially. They wore the hearing aids with the master program home for 1 month and were instructed to complete the same self-paced “bottom-up” training regimen while wearing the master program.10 They returned after the training, and their speech performance on both the master program and the AE program was measured. They wore the hearing aids home for another month, but they were not instructed to complete any auditory training. Their phoneme performance was again measured at the end of the 2-months trial. The test conditions included testing in quiet at 50 dBSPL and 68 dBSPL, and at 68 dBSPL in noise (SNR = +5). Although subjects only wore the master program home during the course of this study, we tested both the master and the AE programs at initial fit (V1), 1-month post-fit with training (V2), and 2-months post-fit (V3). We compared the consonant scores in three ways.

1) Consonant scores over time with master program. Figure 3 shows the performance of the master program at various times for each of the test conditions—at the time of fitting, after 1 month of wearing and training with the master program, and after 2 months’ use of the master program. In general, the master program did not result in any significant change in performance over time for any of the test conditions. This suggests that training with the master program did not bring about an improvement in consonant identification.

2) Consonant scores over time: master program vs Audibility Extender. The AE program was also tested at the same session as the master program during the course of the follow-up study (even though the AE was not used). Figure 4 shows the average consonant scores across visits with the master program (left side) and with the AE program (right side). An immediate observation is that the average scores were similar between the master program and the AE program at each visit.

These results are significantly different from those reported in the first study5 where an improvement over time with the AE program was observed. In this case, training with (and use of) the master program did not improve its performance or result in any improvement on the AE program. This supports the hypothesis that time/experience alone or high frequency cues alone are not sufficient to bring about improvement. Both must be available to bring about improvement.

3) Consonant scores over time with Audibility Extender: comparison with previous study. Figure 5 compares the relative change in consonant scores measured with the AE program at the 1-month and 2-months visits from the time the AE program was initially evaluated (ie, first visit). The relative change was separately plotted for the first study5 and the follow-up study using data only from the 5 subjects who were common to both studies. A positive percentage represents improvement in AE performance at the first and/or second month of AE use relative to the initial visit; a negative percentage represents a poorer performance during those same intervals. The percentage is calculated by taking the difference between the AE scores between subsequent visits and the initial visit and dividing the scores measured during the initial visit of each study.

Figure 5 shows a positive change in the NST consonant scores measured with the AE program during the Kuk et al5 study where training was provided when the subjects wore the AE program. More improvement was noted at the second-month visit than at the first-month visit (re: initial visit). On the other hand, the same was not observed with the AE program during the follow-up study where training was provided only to the master or non-AE program. This again confirms that use (and training) of the AE program is necessary to reveal the contribution of the high frequency cues made available through the AE.

Conclusion

The results of the follow-up study show that training and experience with the master program do not improve performance on the ORCA-NST as it did with training with the AE program in the Kuk et al5 study. These results, along with those reported by Kuk et al5 and Auriemmo et al,2 reinforce the idea that training and use of the AE over time improve performance. However, training and use of the master program over time did not improve performance for this group of hearing-impaired participants with a precipitous high frequency hearing loss.

It is important to recognize that, while training may improve performance, the amount of improvement will be limited by the (un)availability of the audible cues. Training may improve general processing attributes that affect performance, such as attention. It may also help individuals develop compensatory strategies, such as communication strategies, to overcome hearing impairment. However, without the necessary auditory cues, training would probably be more effortful and the results more limited. On the other hand, training with the availability of necessary cues makes learning of those cues easier and communication less effortful.

The use of AE facilitates the learning of high frequency sounds during training. Training alone is not a substitute for a sub-optimal amplification.

References

- Kuk F, Korhonen P, Peeters H, Keenan D, Jessen A, Andersen H. Linear frequency transposition: extending the audibility of high frequency information. Hearing Review. 2006;13(10):42-48. Accessed October 19, 2010.

- Auriemmo J, Kuk F, Lau C, Marshall S, Thiele N, Pikora M, Quick D, Stenger P. Effect of linear frequency transposition on speech recognition and production in school-age children. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20(5):289-305.

- Korhonen P, Kuk F. Use of linear frequency transposition in simulated hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2008;19(10):639-650.

- Kuk F, Peeters H, Keenan D, Lau C. Use of frequency transposition in thin-tube, open-ear fittings. Hear Jour. 2007;60(4):59-63.

- Kuk F, Keenan D, Korhonen P, Lau C. Efficacy of linear frequency transposition on consonant identification in quiet and in noise. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20(8):465-479.

- Sweetow R, Sabes J. The need for and development of an adaptive Listening and Communication Enhancement (LACE) Program. J Am Acad Audiol. 2006;17(8):538-558.

- Kramer S, Allessie G, Dondorp A, Zekveld A, Kapteyn T. A home education program for older adults with hearing impairment and their significant others: a randomized trial evaluating short- and long-term effects. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(5):255-264.

- Martin M. Software-based auditory training program found to reduce hearing aid return rate. Hear Jour. 2007;60(8):32-35.

- Kuk F, Lau C, Korhonen P, Crose B, Peeters H, Keenan D. Development of the ORCA Nonsense Syllable Test. Ear Hear. 2010; 31(6):779-795.

- Kuk F, Keenan D, Peeters H, Lau C, Crose B. Critical factors in ensuring efficacy of frequency transposition, Part 2: Facilitating initial adjustment. Hearing Review. 2007;14(4):90-96. Accessed October 19, 2010.

Citation for this article:

Kuk F, Keenan D. Frequency transposition: Training is only half the story. Hearing Review. 2010;17(12):38-46.