Interventional Audiology Services: Healthcare Economics | October 2016 Hearing Review

Hearing care professionals will assume a significantly greater role in general healthcare, and one big reason is obvious: money.

Why will hearing healthcare professionals find themselves increasingly involved in general healthcare and working more closely with physicians? The cynical answer is “money.” In today’s patient-centric and value-based reimbursement system, if physicians wish to be compensated at higher levels, they will need the skills and services of hearing healthcare professionals—facilitating better patient communication and adherence to their recommendations, while securing the better health-related outcomes shown to be associated with better hearing. The time is now to start educating physicians about this opportunity—before your competition does.

Healthcare economics might seem a rather abstract topic for hearing care professionals seeking to improve the financial performance of their practices. However, economic forces in healthcare are about to create a game-changing opportunity for the hearing healthcare industry. The reason for this has to do with changes in how and why physicians—especially primary care physicians—are being compensated by insurers, including Medicare and Medicaid.

Most physicians today grumble about how insurance companies and regulators are changing their compensation arrangements. New changes that are underway in those compensation systems will soon cause a great deal more grumbling. It is not that the physicians are being paid less; while some will be, many others will be paid significantly more. The complaint by physicians is more that reimbursement is being tied to activities they did not do before. They are being financially rewarded if they change how they practice, and punished if they do not. Change of this sort is painful, so physicians grumble about being forced to change their routines even when they are also being paid more to do so.

For reasons which I describe in this article, hearing care professionals in the next few years who understand what is going on in healthcare from the economic perspective, and are willing to put that knowledge to use, will be able to improve their own financial situation significantly. While healthcare economics is currently causing physicians pain, their pain can be transformed into the hearing care professionals’ gain.

The root of the economic issue for healthcare has to do with cost, but it is not simply that healthcare is expensive. The issue is that the national expenditure for healthcare is increasing, and specifically that it is increasing faster than the rest of the economy for many decades. It is this trend that is causing economists to be alarmed. The problem is that as healthcare consumes more and more of the total economy, less of the economy remains available for everything else.

Economists use the “Gross Domestic Product” (“GDP”) to measure the size of the total US economy. A century ago, healthcare consumed a little less than 2½% of the GDP. Fifty years ago it was 5%. Today it is almost 20% of the GDP, which translates currently to nearly three trillion dollars a year going to healthcare in the US.

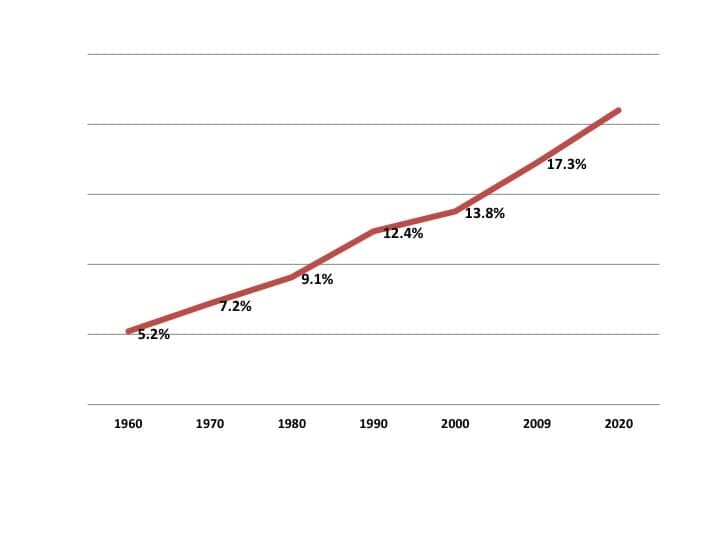

Figure 1. US healthcare spending as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

It could reasonably be argued that three trillion dollars for healthcare in a country with a total GDP of 18 trillion dollars is about the right amount, or it could be argued that it is too much, or that it is too little. However, the upward trend in healthcare costs is far more interesting, and worrisome, than the actual number. Figure 1 shows this trend for the last fifty-plus years.

The obvious point of Figure 1 is that the percent of GDP spent on healthcare is steadily rising. The important issue is not the specific percentage of GDP currently devoted to healthcare; the problem is what will happen if that percentage continues to increase in the future.

Obviously, such an upward trend cannot continue indefinitely. If it did, the country would end up devoting 100% of its economy to healthcare, in which case there would be nothing else produced: no food, no clothing, no houses, no cars, no schools, no roads, no national defense, and no entertainment (except the awful jokes told by my colleagues working in healthcare). The economy would be devoted only to healthcare, which is clearly impossible. The rise in healthcare spending (as a percentage of GDP) will obviously stop somewhere before it reaches 100%. But where? At what level of spending? And when? And how will the upward trend be stopped?

While there is no crystal ball with the answers to those questions, economists generally have come to two conclusions:

1) Healthcare spending is already high enough to be a significant problem; it is causing internal problems in the economy and makes the United States less competitive than our trading partners internationally (all of whom spend less than we do on healthcare). Our high spending on healthcare makes US labor costs higher than they would be otherwise, and that results in the loss of US jobs to other countries.

2) The time to start taking action to lower the rate of increase in healthcare spending is now because it will take many years, probably decades, to stabilize healthcare spending as a percentage of the GDP.

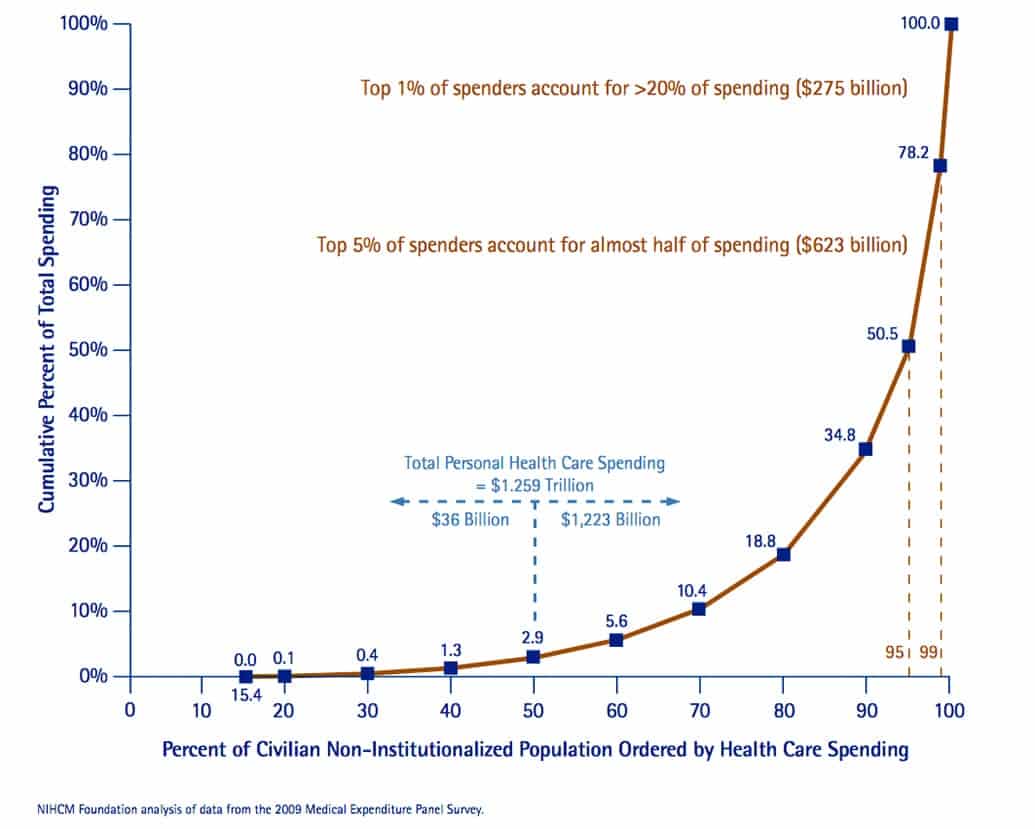

Figure 2. Most of the US healthcare spending is devoted to a relatively low population of spenders; almost half of all healthcare expenses is devoted to the top-5% of spenders. The figure shows 2009 data; today’s dollar spending is considerably higher. Source: NIHM Foundation (NIH) analysis of data from the 2009 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

The answer to the question about how to reduce the rise in healthcare spending is the answer that is making my medical colleagues grumpy and should bring a smile to savvy hearing care professionals. To answer that question, one needs to understand a simple but not well appreciated fact about the nature of healthcare spending: almost all of the healthcare dollar is spent caring for a small percentage of the population (Figure 2).

If you really want to understand the US healthcare system, then Figure 2 is worth taking a few minutes to examine. On the right hand side of the curve, one can see that 5% of the population (those who spend the most because they have the most need for treatment) are responsible for about 50% of the total amount that the nation spends on healthcare in any given year. Looking at the left half of the graph, one sees that the half of the population that spends the least amount on healthcare is responsible, in total, for less than 3% of national healthcare expenditures. To repeat: 5% of the population spends 50% of the national healthcare dollar, while 50% of the population in aggregate spends less than 3%. The concentration of healthcare spending in a small percentage of the population is one of the most basic, yet also one of the most remarkable facts, in American healthcare economics.

We know who the people are who spend little or nothing on healthcare and who occupy the left half of the chart: they are healthy, mostly younger adults and children. They enjoy good health, take good care of themselves, and rarely need medical attention. On the other hand, the 5% of the population spending half of all healthcare dollars are generally older and suffer from multiple chronic diseases, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, lung disease, or neurologic disease. Some of them have cancer. There are a relatively small number who are younger (including newborns) who have a wide variety of less common but very expensive-to-treat illnesses.

While some of the population of high cost individuals will die in the next year or two (they are in their last year of life and thus will fall off the graph the next year), most of them will live for many years to come. This is a particularly important point. Almost all of those in the highest spending 25% (the right quarter of the graph) will, from one year to the next, remain where they are on the curve or move even higher up the curve; it is unusual for individuals to move down (toward the left) on the graph from year to year.

This high-cost population tends to take multiple medications, to see doctors frequently, and they often end up in emergency rooms and as inpatients in hospitals and nursing homes.

One economic idea that Figure 2 suggests is that, in order to reduce healthcare costs, one needs to focus on the population that will be spending the most money. This naturally raises the question of whether or not the specific individuals in the high cost area of the curve can be identified in order to improve the way they are cared for. The answer is yes, they can be. The economists use the word “risk stratification” to describe the process for distinguishing these patients from the rest of the population; physicians call these patients the “high risk” patients in their practice or, to use the medical vernacular, these patients are the “frequent fliers.” And, just about every medical practice has a group of “frequent flyers.”

The lesson from this picture of risk and spending is clear. If one focused on doing things to lower healthcare costs for the population on the left hand side of the graph (those who spend the least) and reduced their healthcare expenditures by, say 20%, one would reduce total healthcare spending by less than one-half of one percent. Furthermore, reducing the spending on that population would be very difficult (it is difficult to make healthy people, who are up-to-date with their preventive care, even healthier). Even if one reduced their cost of care, it is likely that some beneficial spending would be eliminated in the process.

If, however, the focus was on reducing the other half of the population’s expenditures (those who spend the most) by 20%, total spending would also decline by almost 20% too: an enormous gain.

But is that possible? To understand the answer, we need to take a closer look at this population that spends so much of the healthcare dollar.

Making the High Risk Population Healthier (and Less Expensive)

Fifty years ago, these patients with multiple conditions who were prone to end up in the hospital and to generate the highest costs were both easier and less expensive to take care of. There were not as many different medications to give them; there were not as many different specialists for them to see; there were not as many blood tests, scans, or endoscopes that could be employed to better understand their illnesses; there were no vascular stents to put in them or robots to take things out of them.

The complexity of the care for these high cost patients today turns out to be a key to the idea that it is possible to simultaneously improve the quality of their care, while also lowering the cost of the care. This idea seems counterintuitive. We usually think that higher quality will cost more money; how can one produce higher quality, yet simultaneously lower costs?

The answer is that a significant portion of the care that these high-risk patients receive, and thus of the healthcare costs generated, is due to episodes of illness that could have been prevented from happening. Furthermore, it does not cost much to avoid those illness episodes. The amounts that could be saved are significant: perhaps as much as a quarter of all healthcare costs could be avoided, if each of these high-cost patients predictably received the right care at the right place at the right time.

The best way to illustrate why there is so much potential for savings is with an example. Consider Mrs Smith (a fictitious patient, but nevertheless, one who is quite familiar to any primary care physician). Mrs Smith is a 70-year-old woman with diabetes and heart disease who has routine appointments several times a year with her family doctor, as well as appointments with her cardiologist and endocrinologist.

The physicians are often adjusting her multiple medications either in dosages, timing, or sometimes with changes in type of medications prescribed. These physicians work in separate offices, and though they are reasonably careful to communicate with each other by exchanging copies of their visit notes, such communications are prone to delay—particularly today when physicians have multiple different electronic medical record systems that do not exchange information easily (if at all).

In this situation, it is very common for a physician to adjust Mrs Smith’s medications, yet fail to effectively communicate the change to the other doctors involved in her care. As a result, Mrs. Smith receives multiple different instructions as to how to take her medications from multiple different doctors at multiple different times. Before long, she is probably taking her medications incorrectly. While this is usually not life threatening, it turns out to be a very common cause of problems which lead to excessive phone calls, appointments, ER visits and, occasionally, hospitalization. The total cost of just the ER visits and hospitalizations due to simple medication administration errors in the United States today is many billions of dollars a year.

Medication errors such as Mrs Smith is prone to experience are just the tip of the iceberg. There are opportunities for communication failures whenever a patient talks to a physician or nurse, in person or by phone, in the hospital, ER, or doctor’s office. The more complex the patient’s care and the more providers the patient sees in the course of a year, the more opportunities there are for error. Communication errors are clearly only part of the quality problem that needs to be fixed in order to improve value in healthcare, yet it is a very significant part of the cost puzzle.

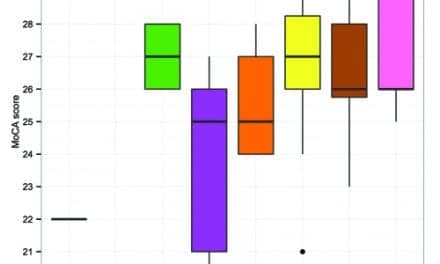

Figure 3. The average decline in hearing thresholds as a function of age. Adapted from earlier work by the US Army and courtesy of Neil Bauman, PhD, from his article “The Bizarre World of Extreme Reverse Slope (or Low Frequency) Hearing Loss” found at: http://hearinglosshelp.com/blog/the-bizarre-world-of-extreme-reverse-slope-hearing-loss

The mention of “communication” should, at this point, begin to convey to hearing care professionals why healthcare economics is a topic relevant to their practices. As it turns out, Mrs Smith’s primary care physician has thought for years that she (like many elderly patients) might have a hearing impairment. However, she has never complained of hearing difficult to any of her physicians, nor has hearing loss seemed to have been a serious problem when they were speaking to each other in the quiet exam room environment.

However, Mrs Smith actually does have hearing loss which occasionally causes her to misunderstand or fail to hear parts of the instructions physicians and nurses have given her, especially in the ER, hospital, or over the phone. At such times, she rarely asks for the instructions to be repeated: from her viewpoint, the doctors, pharmacists, and caregivers are always very busy and, anyway, she has thought for years that the medications do not seem to make her feel better or worse no matter how she takes them.

As Figure 3 shows, Mrs Smith’s problem with hearing is common among the elderly. The idea that even mild hearing loss is a common contributor of avoidable medical costs has been suggested for decades, but it has not previously led physicians to become more aggressive about the diagnosis and treatment of mild hearing loss.

Until now. The last part of this discussion of healthcare economics is about why physicians, especially primary care physicians, are about to become much more interested in the diagnosis and treatment of mild-to-moderate hearing loss in their patients.

Hearing Loss: A Major Obstacle to Patient Engagement

In the last decade, it has been increasingly recognized that many episodes of illnesses in the high-risk population can be avoided by relatively simple systems which help avoid miscommunication, and which encourage and enable the patient to participate more actively in their own care. The general process of communicating with patients and engaging them in doing a better job taking their medications, following dietary instructions, and leading a healthier lifestyle has been called the process of “patient engagement.” And hearing loss—especially the mild-to-moderate high frequency hearing loss seen in a large number of patients over 65—can be a major obstacle to patient engagement.

Patient engagement, for those patients with chronic illnesses such as diabetes, lung and heart disease, is critically important if patients such as Mrs Smith are to avoid unnecessary ER visits and admissions. These avoidable admissions have become the focus of considerable attention by insurers and regulators because they are a major source of excessive, preventable healthcare costs. This is where the medical economic concepts presented thus far in this article come together.

As it turns out, there are many things a primary care physician can do that are important in preventing unnecessary hospitalizations among high risk patients like Mrs Smith. In the next few years there will be more and more attention paid by insurers —especially Medicare—to encourage primary care physicians to do the things necessary to keep their high-risk patients as healthy as possible, and thus, out of the hospital. If the physicians are doing these tasks well, they will receive higher reimbursement for their services. If not, they will receive less. The amounts involved will increase year by year; in 5 years, the implementation of the current regulations will create a range of about 30% between what physicians receive from Medicare for performing the same services.

General internists in a busy practice can easily have a third or more of their visit volume be from Medicare. Along with other financial incentives from other insurers that are being introduced, the total practice revenue at risk for a primary care provider will be more than enough to grab their attention.

Many primary care physicians do not yet understand the details of what Medicare and other insurers are doing and how big the dollar impact will be. However, greater numbers of primary care physicians are embracing what is called “value based reimbursement” and “value purchasing” policies and regulations. Physicians who are doing so are already adding significantly to their incomes by making sure their patients are staying up to date with their appointments and check-ups, by making an effort to keep their patients engaged in their own care, and by giving their high-risk patients special attention in ways that prevent those ER visits and hospitalizations that are potentially avoidable.

Yet most physicians do not know as much as they need to about the problems that undiagnosed and untreated mild to moderate hearing loss causes for their patients. Most physicians do not realize that even mild hearing loss can lead to miscommunication, poor patient engagement, and thus, with the new forms of physician reimbursement, less income for the physician’s practice. When physicians connect the dots, they will refer more and more patients for hearing loss evaluation and treatment.

Audiologists and other hearing care professionals can help physicians connect the dots by educating them about the importance of identifying and treating patients with mild to moderate hearing loss. As physicians learn more about how better hearing healthcare will translate into better overall patient care, the number of referrals physicians make for the evaluation and treatment of hearing loss will increase significantly.

John Bakke, MD, MBA, is a General Internist and Senior Consultant for Zolo Healthcare Solutions.

Correspondence to Hearing Review or Dr Bakke at: [email protected]

Original citation for this article: Bakke J. Interventional Audiology Services: What Hearing Care Professionals Need to Know About Today’s Healthcare Economics. Hearing Review. 2016;23(10):16.?

Other Articles in This Special Edition about Interventional Audiology Services:

Introduction: Interventional Audiology Services: Meeting the Demands of Today’s Consumer, by Brian Taylor, AuD, Guest Editor

Intervening in the Care of More Patients: Beyond Clinic-based Testing and Fitting, by Brian Taylor, AuD

Incorporating Health Literacy into Your Hearing Care Practice, by Jennifer Gilligan, AuD, and Barbara E. Weinstein, PhD

Patient Engagement Through Interventional Counseling and Physician Outreach, by Robert Tysoe

Patient Complexity and Professional Time: Improving Efficiencies in the Service Model, by Dan Quall, MS, and Brian Taylor

Thinking Outside the Booth: Three Overlapping Categories of University Audiology Outreach, By Melanie Buhr-Lawler, AuD